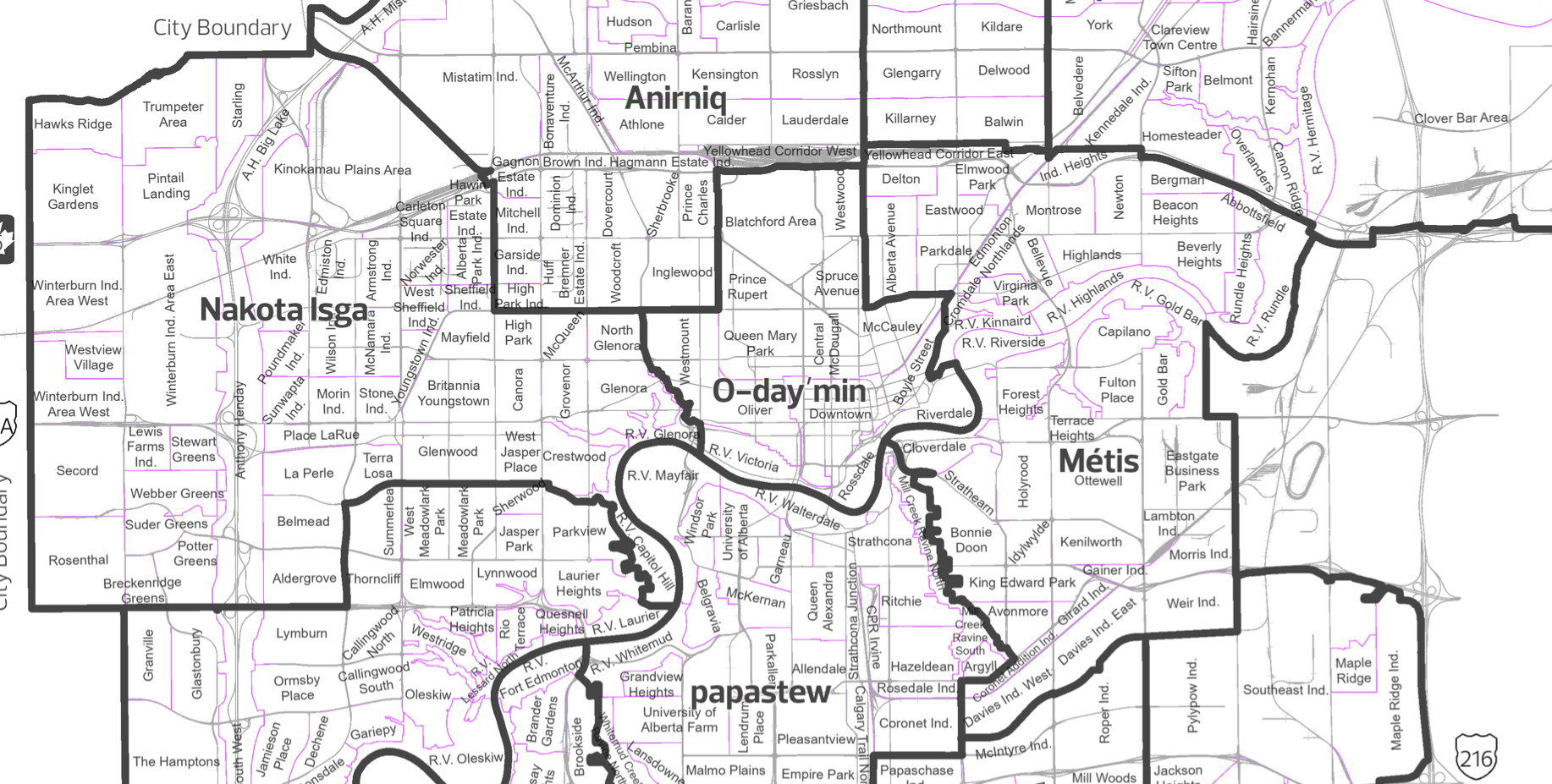

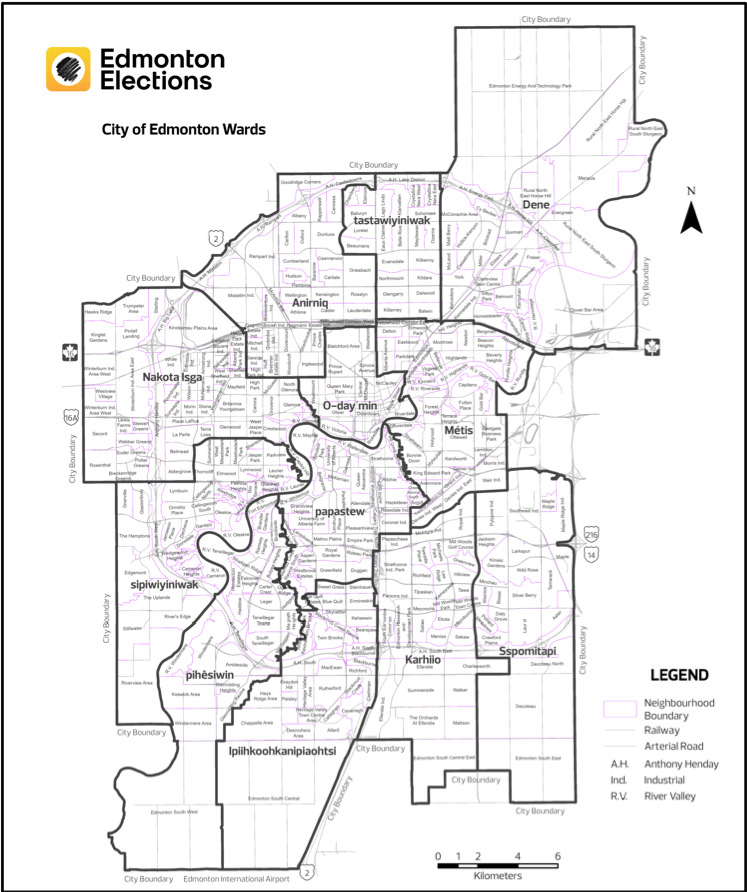

On December 7, 2020, following over a year of planning and work by the Edmonton Boundaries Commission, Edmonton City Council voted 10-3 in favour of establishing 13 new city wards with Indigenous names. The process of redesigning the ward boundaries was necessitated by expanding City boundaries, and the need to redistribute populations more fairly. Due to rules outlined in the Municipal Government Act, City Council and Administration were required to approve any changes to boundaries and wards one year before the 2021 Municipal Election. This requirement created a time crunch for leadership and may have contributed to the initial approaches they took. Beginning in the Fall of 2019, work was initiated to redraw the boundaries and rename the wards, in order to have everything in place before the end of 2020.

During the final stages of the process in June 2020, members and advocates from Edmonton’s Indigenous communities voiced their concerns regarding proposed ward names and Indigenous naming processes within Edmonton. The names being brought forward by the City’s Naming Committee, saddled with a one-week deadline, fell short of seizing the immense potential that existed. Ward names like Scona, Jasper Place, Whitemud and Gateway were sprinkled amidst general direction names like North and West. In any other moment in time, these names would have been sufficient for City Council and many Edmontonians. However, for the past decade, the City administration has been working diligently to build relationships with Indigenous communities, paying special attention to re-framing the history of Edmonton. Advocates and experts spoke to Council advocating for them to seize the immense opportunity to do some justice to Indigenous histories on this land.

Council heard about how naming things after Lord Strathcona, a leader of the Hudson Bay Company and namesake of the Town of Strathcona, was a step backward in reconciliation. They were educated on how naming things after English words- such as Whitemud and Gateway- continued to erase Indigenous history, seemingly ignoring the usage of the ochre in Whitemud Creek and the importance of Calgary Trail to Indigenous peoples. By choosing generic direction names, Council missed the mark on naming and a real educational opportunity. To the surprise of presenters, scholars and Elders, Council unanimously agreed with these assertions and directed work on establishing Indigenous names for the 12 new wards. Speakers committed to bringing together a diverse swath of Indigenous communities in Edmonton while also reaching out to those with historical connections. Provided with a tight timeline of 3 months, work was going to have to unfold quickly and perfectly in order for the task to be completed.

Initial conversations of this Indigenous Naming Committee circled around strategy, and how best to approach the task at hand. It was discussed and decided early on that this naming initiative presented an opportunity for Indigenous reclamation. A reclamation of traditional practices, and specifically, a return to matriarchal decision making. Lead through ceremony and spiritual guidance, the initiative began to strategize on the safest path forward. Two co-chairs or Circle Keepers were established to keep the group focused on the objective and it was determined that the committee would be composed of only women. From this, iyiniw iskwewak wihtwawin, or Indigenous women leading, was created and knowledge keepers, language speakers, and Elders were invited to participate. It was vital that the iyiniw iskwewak wihtwawin be composed of representatives from the language families present in and with a connection to Edmonton. It was decided early on that some names required would be those of Treaty No. 6 Nations reflected through language, recognition of the Papaschase Band, a Blackfoot connection and Métis history in Edmonton, as well as placemaking for the LGBTQ2S+ community. It was expressed by Elders involved that each of the language families considered be given a ward with connection to the North Saskatchewan River; both recognizing the importance of water in our communities and the utilization of the river as a traditional travel route. By embracing a strategy built upon equity and space-making, the work began to unfold.

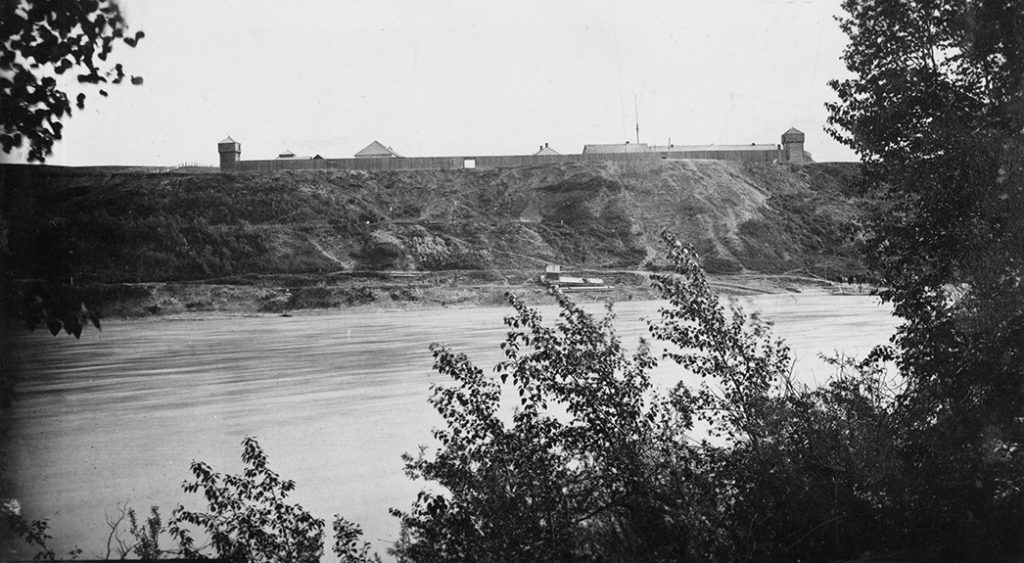

Conversations around the table ranged from the deeply emotional to the hilarious. Laughter and tears were present during all conversations, including on field visits to places of importance. We paid respects to ancestors in the heart of the city, visited those who never returned home and imagined possibilities of what could have been. Participants were educated on ceremonies that took place in certain locations, violations that occurred in places of healing, communities dispossessed, and bonds created through trauma. We heard stories of people coming for aid, learning new languages and never returning home. Layered in all of these conversations was Indigenous understanding and practice. We sang songs, participated in a Nightlodge ceremony, and helped each other heal in one way or another. The process shifted from a naming initiative, to one of reclamation and place-making. Indigenous people, through determining names, were given a chance to reconnect to their traditional lands, speak the truths of this place and to finally be at home on their own territory- something centuries in the making.

The experience, however, was not without its challenges. When the names of the new wards were finalized by iyiniw iskwewak wihtwawin and gifted to the Naming Committee, and ultimately City Council, the acceptance was not universal. In a vote of 9-4 in September 2020, Council accepted the names begrudgingly. There were detractors who spewed the usual veiled racism to which Indigenous people have unfortunately become accustomed. Comments ranged from difficulty in pronunciation, spelling issues, translation concerns and the need to retain a numbered system. Some Councillors raised concerns about the geographical nature of the names, and the stipulation that it did not exist for some of the names proposed. Committee members, expecting this type of pushback, were disappointed that an opportunity for understanding had been reduced to misnomers and conjecture. Those who had initially supported the naming process unanimously were now questioning the very task they had given to the iyiniw iskwewak wihtwawin. There was a feeling, which many Indigenous people have experienced, of being given an impossible task, succeeding, and having the outcome questioned. Regardless, the names were gifted and are now law.

For years to come, Indigenous people and non-Indigenous can learn and reconnect together around these names. They can educate one another in the history of this place and walk together in creating a new future. Canadians can learn a language new to them, but so old that it is intertwined with the landscape. Edmontonians can take pride in being a leader in the country once again. In addition to the numerous articles written about the names and their meaning, as well as resources that exist on City resources, it was important that arguments against the names be contested by explicating some of the deeper connections of the names. Some of these unknown truths and connections are elaborated on below:

Nakota Isga (Nakota) was selected as the only ward that includes Stony Plain Road in its entirety and would have been a traditional place where the Nakota from Alexis and Paul would have camped.

Anirniq (Inuktun) was selected as it contains the Camsell Hospital in the Inglewood neighbourhood:a place where Inuit were held during the tuberculosis epidemic, with some never returning home.

tastawiyiniwak (Cree) was selected because, as shared by Circle Keeper Terri Suntjens, it is the direction in which the grandmother who looks after the In-between people is located.

Dene (Dene) was selected as it represents the direction in which Dene from northern communities would travel into the city, as well as containing a connection to the North Saskatchewan River that connects our communities.

O-day’min, translated “heart-berry” from the Anishinaabe. It was selected as this Ward sits in the Heart of the City, as well as, in the North Saskatchewan River Strawberry watershed.

Métis (French/Michif) was selected due to the historical river lot system that existed before City expansion and maintains a connection to the River for our apihtaw brothers and sisters.

sipiwiyiniwak (Cree) pays homage to the Enoch Cree Nation, as much of this ward falls within their traditional reserve boundaries prior to surrender.

papastew (Cree) pays homage to the Chief of Papaschase reserve as it contains the Two Hills in which his people settled and also served as an important lookout point.

pihêsiwin (Cree) was selected as the Terwillegar area contains former Sundance grounds, and contains the shape of a Thunderbird when examined on a map.

Ipiihkoohkanipiaohtsi (Blackfoot) was selected by the Blackfoot as it would have contained traditional buffalo hunting grounds and served as a camping spot for them during those hunts.

Karhiio (Mohawk) was selected to pay respect to the Michel Band and their descendants who would have had interactions with Papaschase people, in addition to the fact that the area is well forested.

Lastly, Sspomitapi (Blackfoot) was selected to pay homage to the Manitou Stone, and when travelling to Iron Creek where the stone was stolen from, Blackfoot would have travelled through this area, possibly stopping to gather with Papaschase and Enoch families.

Rob Houle © 2021