Edmonton is a unique blend of indigenous and introduced species. As a sprawling city that contains eighteen-thousand acres of river-valley, much of which is forested, Edmonton has some trees that may be as old as recorded history and could yet live for thousands of years – should we let them.

The youngest trees in the city are newcomers – horticultural experiments that may one day leave their mark on Edmonton’s landscape and history. Lilacs from Eastern Europe, cherries from Asia, and Lodgepole pines that colonized a barren landscape after the last ice age are fixtures on Edmonton’s landscape – plants around us that reflect a cultural heritage that spans millennia.

As humans selectively harvest, spare, clear cut, burn, tend, and relocate plants, we cultivate living witness marks across the landscape. To survey the plants in a given geography is to survey its human cohabitants – the older the tree, the deeper the relationship is rooted. Through this lens, the trees are artefacts in a shared arboretum – a tree museum that we helped curate.

One can wonder at the trees as a historian does about archival resources: What kind of tree is this? From where is it native? How old is it? What is its relationship to people and different cultures? Reading the arboretum requires curiosity but provides insight to those who are patient.

Every tree has a story. Here are three of those stories.

The Red River Stowaway

In 1874, Laurent Garneau, a Métis soldier in Louis Riel’s Red River Resistance, and his wife, Eleanor, set off West. Travelling with them – perhaps tucked in a pocket – was a seed from the home they had left. When the Garneaus arrived on the south bank of the North Saskatchewan River (at the North-East corner of the University of Alberta), they built a home. Upon settling in, they planted their stowaway, a Manitoba maple (Acer negundo), in their yard.

Acer negundo does not produce fruit or nuts, and while the Garneaus could have used wood, a single tree would not yield much for many years. The maple would have been less essential than vegetables and medicinal plants, so why the Garneaus planted it is uncertain. But why does anyone plant a tree? Maybe the Garneaus’ liked maples, or maybe it reminded them of their home in Manitoba.

For one-hundred and forty-three years, the Garneau tree grew on the landscape they settled. From that homestead grew the neighbourhood that bears the Garneau name. In 2008, the Alberta Heritage Tree Foundation recognized the tree for its heritage value; however, the City removed the tree in 2017 due to safety concerns.

While the native range of Acer negundo flirts with the province’s southeastern border, all signs point to it being absent in Edmonton until newcomers, like the Garneaus, arrived and introduced it. Anyone familiar with A. negundo might find it peculiar that early settlers prized the Manitoba maple so highly. Rutherford House has a Manitoba maple in the front yard. In 1954, the Provincial Government attempted to move a 79-year-old maple planted by Richard Hardisty, chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, to the south-side of the Legislature grounds. It was a move that was ultimately unsuccessful. The City briefly planted A. negundo as boulevard trees – a practice they dropped due to pests, diseases, susceptibility to damage, and the trees’ tendency to spread. Roughly three-thousand Manitoba maples – mostly in the core [1]– remain in the City’s inventory. Scattering seeds into adjacent yards, alleys, and vacant lots, the tree can now be found almost everywhere in Edmonton. Some consider it a weed. But whatever one feels about Manitoba maples, they are ubiquitous on the landscape.

Wild Goji

While riding the funicular, one could be forgiven for not noticing the odd plants which surround. However, turn to face the Hotel MacDonald and one will see a sweeping shrub with tiny purple flowers and red-orange berries that hang like earrings. Goji berries (Lycium barbarum), a relative of the tomato, potato, pepper, and eggplant, exchange their Himalayan origin with a surrogate Edmonton landscape. As the Goji grow towards the downtown skyline, their leggy branches bow under their weight, touch the ground, and root. Branch-by-branch, year-by-year, the thorny Goji forms an impenetrable colonial-mat encircling the historic hotel.

Often used in savoury dishes, goji can be described as tasting like a blend of tomato and bell pepper. Likely brought to Edmonton by its first Chinese community members, the plant was (and remains) a source of food and medicine, while offering a connection to another home. To this day, Goji can be found in backyards and alleyways throughout Chinatown and neighbouring communities.

How Goji became rooted along the banks of the North Saskatchewan from McDougall Hill Road to Riverdale is not clear. Local historian and author of Why Grow Here: Essays on Edmonton’s Gardening History, Katherine Chase Merritt estimates that at least fifteen Chinese-run market gardens once dotted the City, including sites at Victoria Park, Riverdale, Walterdale, Louise McKinney Riverfront Park, and the sites of the Royal Glenora Club and Mayfair Golf Courses.[2] One theory is that the wild Goji are perennial remnants from one or more of these gardens. Another theory suggests that birds spread the seeds from plants cultivated in nearby Chinatown. Whatever the source, development pushed Chinatown further north along 97th street and likely contributed to the disappearance and abandonment of the market gardens. Whatever the case, the wild Goji remain as a horticultural mark on the Edmonton landscape.

A Trembling Giant

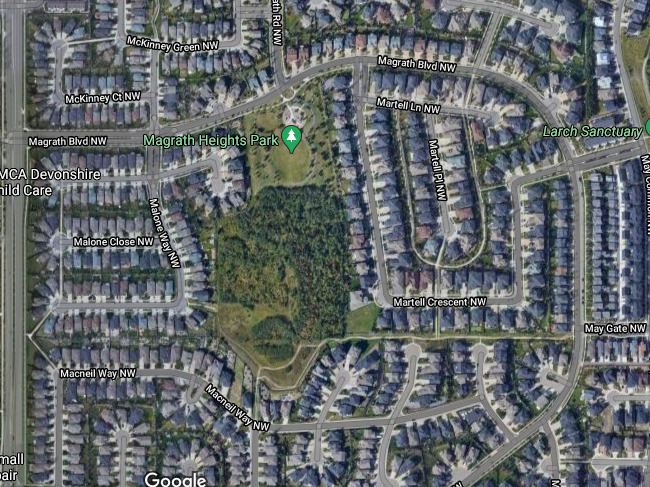

On the south-end of Magrath Heights Park, a quaking giant of a tree stands. Easily mistaken for an entire forest, the trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) sprouts tree-sized branches from its subterranean body and exists as a mass of roots growing in all directions, searching for water, nutrients, and a mate.

Contained by the City, the aspen is a remnant of an indigenous landscape once common to the area: a patchwork of meadows, wetlands, and mixed deciduous forest known as Aspen Parkland. Fortunately for the giant, the same regenerative sprouting of heads that allows the tree to crawl across the landscape makes it nearly immortal. As old tree-sized branches die and decay, their nutrients are re-absorbed and incorporated into new branches that sprout and take their place. Capable of living tens of thousands of years, it is possible that the tree may be older than the City and may still outlive it; that is if we don’t pave over it.

In contrast to the giant Aspen, the Garneau Tree and wild Goji are ecological colonizers on an indigenous landscape. While their stories are worth telling, we should not overlook the aspen’s tale of perseverance across time. Taken together, as artifacts in the arboretum, they reflect a complicated, interrelating history.

Trees and humans share the landscape and are coevolving a future character of this place. But our roles are uneven. It can take a hundred years to grow a tree and merely an afternoon to remove it. There’s something incongruous about short-lived people removing three-hundred-year-old trees to make room for thirty-year developments. Unnecessarily removing artifacts from the arboretum robs future generations of shade, stories, and a sense of place. That’s not to say that we can’t remove trees. Like all living beings, trees have life expectancies, and dangerous trees, like the Garneau tree in its final years,[3] may need to come down or be moved, if possible.

One ought to think of trees as cultural and ecological anchors that contribute to a sense of place. Due to this importance, removing a tree should always be considered on the timescale of that tree’s life expectancy. If applied, we might be encouraged to preserve individual specimens as long as possible and, in doing so, allow existing trees to inform future development. When development bends to the landscape (as opposed to the other way around) we’re forced to create something unique in that place.[4] Caring for, growing, and preserving the urban arboretum is not only a tool for growing a better city but also serves as a way to preserve our complex histories.

Dustin Bajer © 2021

Learn more about Heritage Trees with Dustin Bajer on the ECAMP podcast!

[1] A City, like a tree, adds rings of growth to its outer-edge. The oldest growth and the oldest trees are usually found near the center. By examining growth rings, we can see horticultural trends and estimate where to look for the oldest trees.

(https://www.opentreemap.org/edmonton/map/?q=%7B%22species.id%22%3A%7B%22IS%22%3A%225934%22%7D%7D).

[2] Kathryn Lennon, in “Edmonton’s Lost Chinese Market Garden” researches the location of various Chinese market gardens and some reasons as to why they’ve disappeared.

(http://spacing.ca/edmonton/2014/02/19/edmontons-lost-chinese-market-gardens/).

[3] Gone but not forgotten. Eric Jensen from Relic Woodworks preserving pieces of the Garneau tree as gifts for the descendants of Laurent and Eleanor Garneau. (https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/garneau-tree-relic-woodworks-salvage-1.4403764).

[4] In Japan, railway designers were forced to incorporate a 700-year old camphor tree into Kayashima station. The result is truly unique and inarguably more interesting than the generic train station that designers had initially proposed. (https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2017/01/kayashima-the-japanese-train-station-built-around-a-700-year-old-tree/).