In amiskwaciwaskahikan (Edmonton), when you examine the current state of Indigenous relations, initiatives and heritage, one cannot help but be bombarded with the nehiyaw word pehonan. Sometimes it is capitalized to signify importance, sometimes it has a macron or other accent added, sometimes it is pluralized and sometimes it is amplified. However, one consistency in the many documented uses of the word, is its tendency to place Edmonton as an important centre of Indigenous existence pre-Contact, often using the definition of an important gathering/waiting place. While this very well may be the case, Indigenous naming conventions, academic research completed in other parts of the prairies, and engagement with Treaty No. 6 communities, points to a possible misapplication of the name Pehonan and a more recent utilization of the term in Edmonton. Careful consideration should be made for whether or not continuing to apply the term to Edmonton initiatives is tantamount to erasing Indigenous heritage in other parts of the prairies.

Indigenous naming conventions should not be seen as trivial processes. Traditional names, for both people and locations, have a level of sacredness that transcends English interpretations and translations. If we examine traditional Indigenous place names and locations, there has always been a persistent, dedicated and practical process employed to name areas of significance. Given traditional lifestyles based around movement, repeated temporary occupation, and oral communication, it would be nonsensical and confusing to have locations and areas sharing similar names. With relations spread across a vast area, gatherings being reserved for important events, and people speaking many languages, being able to understand and interpret names connected to a definite location has always been paramount. Having numerous places sharing a similar name, or names, would make rendezvous with familial relations and other tribes nearly impossible. For instance, if one intended on meeting with a hunting party at Pehonan, it would be difficult to understand where people were stopping if there were numerous pehonan. Indigenous naming conventions are designed to avoid these types of mistakes, and are applied in such a way that many people would be able to conclude and understand where people are heading.

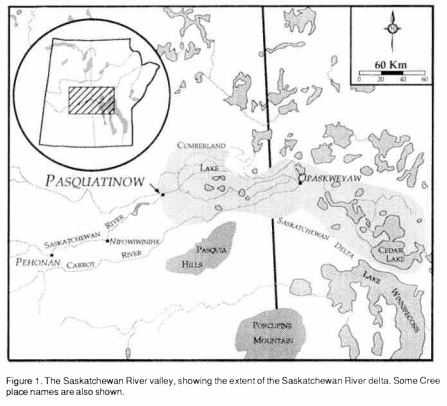

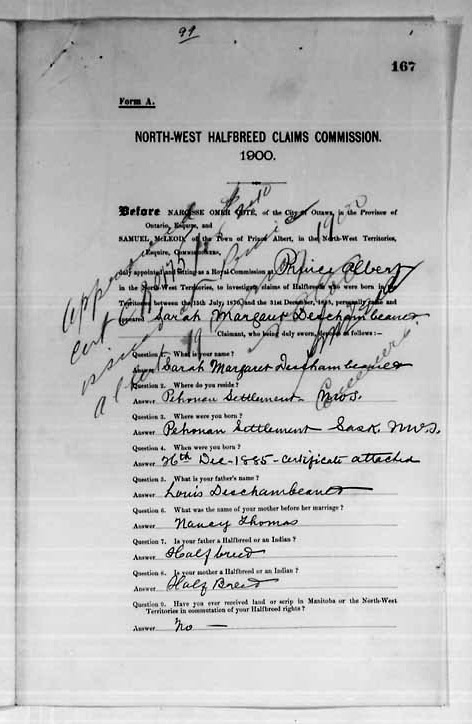

Following these Indigenous naming tenets, one can begin to view academic research undertaken in Saskatchewan from the early 1980s onward with increased validity. Early maps from explorers, whom we know were informed and guided by Indigenous people, make reference to waterways and locations near present day Prince Albert as a Pehonan Complex. Academics like Meyer, Gibson, Russell, Kimko and Paquin authored numerous pieces referring to the cultural, ceremonial and ecological significance of the Pehonan Complex. They write: “The fur-trade and church-missionary accounts provide evidence that in the late winter/early spring (before breakup) the occupants of various parts of the Saskatchewan River valley moved to gathering places such as Opaskeyaw (The Pas), Nipowiwinihk (Nipawin) and Pehonan (Ft. a Ia Corne).” Understandings and teachings from First Nations in the area recognize the forks of the Saskatchewan River being the Pehonan, with annual gatherings taking place amongst many tribes prior to venturing in many directions for hunting and ceremonial purposes. This traditional name is reflected in Pehonan Creek, on which Fort a La Corne (Fort des Prairies) was constructed, and also in discussions around important crossing points like pasquatinaw. In the mid-1700s, the Hudson’s Bay Company constructed Fort Carlton near the Saskatchewan Forks, and later in 1875, First Nations leaders would stay near the Fort waiting to sign Treaty No.6 for more than a year. In heritage terms, Treaty No. 6 and its signing would make this location an important waiting place, or Pehonan, once again.

The Saskatchewan River valley, showing the extent of the Saskatchewan River delta with some Nehiyawak place names. Image provided by the author. Pehonan can be seen on the left hand side along the Saskatchewan River.

To investigate the application and location of the term Pehonan with reference to Edmonton, technicians in various projects, including the Heritage Interpretive Plan for the City of Edmonton’s River Crossing project and most notably the Rossdale Historical Land Use Study, asked specific questions about naming, Indigenous uses and First Nations history of Edmonton. Those engaged included Elders and Knowledge Keepers from Treaty No. 6 and 7 communities who were willing to provide insight and guidance. In an almost unanimous fashion, Elders and Knowledge Keepers recognized this place as amiskwaciwaskahikan, or Beaver Mountain House. Some shared stories of the Fort, others provided histories that pre-date the Fort and fur trade, but few, if any recognized this place as a waiting place. In examination of other documents and reports, specifically relating to the Urban Aboriginal Accord, only one utterance of pehonan was observed, and this was reduced to a closing comment by one individual. With no prevalence in historical documents, oral histories or practice prior to the Accord process, one must begin to ask how the term became so widely used here.

Through examination of archival, historical and public documents, it appears that the term pehonan has been in use around Edmonton since the mid-2000s. Much of its use centers around an Urban Indigenous movement of sorts, and the establishment of the Urban Aboriginal Accord. Sources of the term have been connected back to non-Indigenous scholars at the University of Alberta with language around and explanations of the name being very similar to those found in the academic works of Saskatchewan. Most importantly, the centering of this narrative was paramount in the Arts and connected directly to an initiative called the Spirit of Edmonton. This movement sought to create Indigenous focused, branded and commercialized attractions across Edmonton. However, if these initiatives championed a name, understood by many traditional peoples to mean a location in Saskatchewan near the Forks of both North and South Saskatchewan River branches, then do these initiatives further or hamper Indigenous heritage? One could argue, by misapplying the heritage, connection and spirit of a known term to a new place, without paying attention and respect to why the name exists in other locations, those undertaking these activities are committing erasure. By trivially applying names and definitions, one creates a situation in which the teachings, history and knowledge of previous usage of the names is replaced with more modern usage. Similar actions were undertaken when missionaries and Indian Agents began replacing traditional names with more Christian names or when using traditional names for surnames of many people. This not only conflicts with traditional naming conventions, but also erodes the deeper spiritual understandings that names and naming carry in Indigenous ways of being.

With these considerations in mind, one must reconsider ongoing usage of the name pehonan. People must allow traditional practices to return, and respect why certain conventions have always been followed. We must put a stop to the erasure of traditionally named locations in other parts of our territories, respect each other’s heritage and continue to investigate Edmonton’s unique heritage. There is no doubt that Edmonton was an important place for First Nations people travelling the North Saskatchewan River, perhaps a stopping place or place of ceremony, but one must conclude that another location is known as Pehonan. Most recently, through the Indigenous Ward Naming process, names such as pehisiwn, sipiwiyiniwak and others have been brought forward by language keepers. These names may have traditional connections to Edmonton that deserve further exploration, as opposed to participating in the erasure of important locations and history in Saskatchewan. As well, we must avoid the establishment of processes and interpretation of names that leads to pan-Indian approaches. We must begin to embrace the diversity among Nations, be respectful of our shared histories and ultimately tell better heritage stories that do not come at the expense of erasing each other’s histories.

Rob Houle © 2021