Plans are afoot for spring. Sunday was spent scouring the glossy pages full of roots and blossoms in a favourite seed catalog. Gardeners are diehard hopefuls and gardening feels like a gift in these precarious times. This year especially, being isolated and in need of a slice of solace, the prospect of summer’s wealth is a welcome daydream. When the seed packets arrive, every gardener east to west lays out their nascent hoard like a rainbow of optimism. Seeds are a symbol of hope, a promise of riches yet to come.

As often happens, for this gardener/historian, I wondered about the first growers of the fur trade. My tenderfoot Grandfathers come to mind and I envision their pioneer plots of root veggies, holding space for their future successes. Was it the garden that saved them when wild foods were scarce and winters so very long? What can we learn from the gardeners of our past, to help us endure our present predicament?

Newcomers found the broad alluvial plains of what would become the Edmonton area most amenable to planting. Large plots were dug up by stick and shovel, the dark soils redolent with possibility. During the earliest days of the amiskwaciwaskâhikan fur-trade settlement, breaking ground for a garden began in early April or as soon as a spade could pierce the crystalline black earth. Local women and adolescent servants would till out icy chunks of loam, setting the frozen wodges in the sun to thaw. Once the post imported hens or an oxen, the beasts would be set upon the fertile space. Sometimes the gardens were fenced to keep out deer and other animals — a considerable effort given the size of even a two acre plot.

Barley and oats were often the first seeds planted as these common old-world crops grew profusely and offered ample yield. Food supply and spoilage was of grave concern as wheat flour stored in barrels could go rancid or become bug ridden. Vegetable crops were a welcome addition to the diet of fish or fowl augmented with game such as moose, deer, and bison. Although meat might be plentiful, no human can live off protein alone. Vital nutrients to waylay scurvy and other maladies had to be gathered or grown. Traders supplemented their food supply with other country foods such as wild rice, nuts, berries, and fruits provided almost entirely by their Indigenous neighbours.

By early May, with the ground tilled and overnight temperatures hovering around zero, mounded beds were built up for the cabbages. Kegged seed potatoes from last year’s crop would be sliced then planted eyes up. Hardy potatoes, turnips, cabbages, and onions all had to be imported from other forts until crops offered viable produce and seed. Radishes, carrots, and peas did not grow naturally here. Sometimes a certain plant just wouldn’t take due to the mountain winds that arrived unjustifiably in June or the relentless sharpness of August sunlight. Some plant varieties did better than others. Rhubarb of all things, flourished. As did beets.

“The Garden at Edmonton House was made in the Spring of 1814. Its produce last Fall was two hundred Bushels of Potatoes, fifty bushels of turnips, eighty bushels of barley, and two thousand three hundred cabbages.”

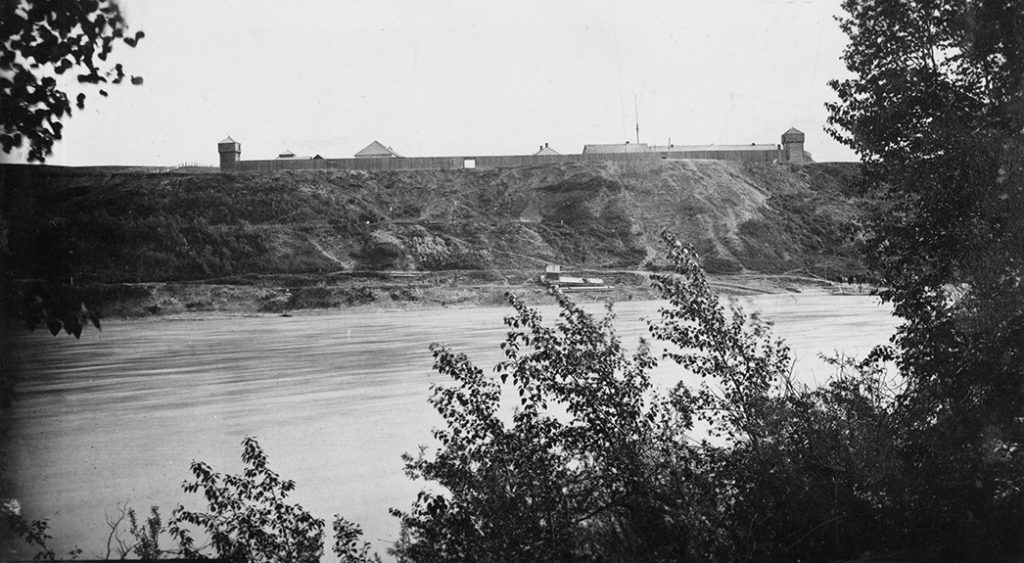

Thanks to its resplendent and prolific gardens, Fort Edmonton quickly grew into the most important trading post on the kisiskāciwani-sīpiy. It supplied the annual York boat brigades with a plethora of quality staples. In 1826 the massive fort garden was noted in a lieutenant’s letters. The abundance of barley, wheat, oats, potatoes, and myriad other vegetables which had served generations of company men and their families was certainly something to write home about! Success was the soil.

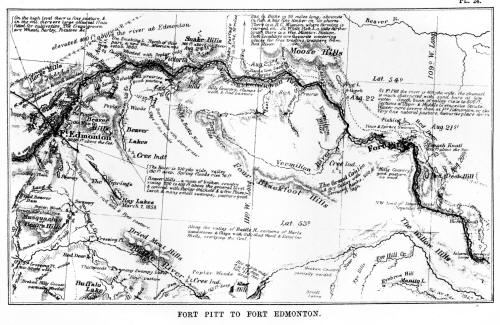

An excerpt from a map of the Palliser expedition (1857-1860.) A copy of the full version of the map can be found here: https://digitalcollections.ucalgary.ca/asset-management/2R3BF1F3BHRTW

As I grid our 21 by 3.5-foot plot for maximum plant density, I also think of my mixed-blood and Métis relations who kept our lineage alive through disease, conflict, and poverty. How did my ancestors make it through countless seasons of adversity? How did they survive the hardships of prejudice and dispossession? As a backyard gardener I know the value of space and how important land is. Our lives truly are derived of water, sunlight, and earth.

While the gathering of wild rice, berries, fruits, roots, sap, and medicinal plants persisted throughout the fur trade, Indigenous people were also avid horticulturalists. A mixed-resource strategy had always been the tradition — a system that allowed our people to thrive. In early spring, families would tap the birch and maple trees for sweet sap. Once the poplars began to leaf out, hunting parties would leave their wintering grounds to follow the bison on their seasonal path. Then, various berries and blossoms were gathered as they came ripe with the restoring light. Vegetable gardens were planted in May, left to ripen and harvest as needed through into early fall when the buffalo were hunted again. The relaxed nature of gardening, with its slow beautiful progression and want for little more than a good watering, aligned perfectly to the cycles of sunlight, people, and creatures.

The roots of Rupert’s Land were well established by the 1850s. Families headed by Scotch or French fathers and Indigenous mothers began constructing homes and cultivated spaces neighboring the fort in the classic river lot style. Dozens of lineages rich in kinship, each with their own gigantic garden of potatoes, cabbages, corn, beans, pumpkins, flowers, and herbs stretched back from the riverbank. Beyond the vegetable gardens lay another two miles of hay and grains. The Métis were underdogs turned kings of the wheat trade — purveyors of the famous Prairie du Chien, Marquis, and Red Fife strains.

In the course of a waning fur-trade and the purposeful destruction of buffalo herds, mixed-blood and Métis people adapted masterfully. Families grew and branched out beyond the fort, establishing communities such as Lac Ste. Anne, St. Albert and Long Lake. From Red River to the Edmonton settlement (and beyond), gardens and agriculture became a central source of nourishment and income for Métis communities.

Canada acquired Rupert’s Land in 1869 and soon the Dominion Land Survey began dividing the prairie into square homesteads: 80 million hectares of gridded settlement sites defying both geography and community lines. Métis families were offered land certificates (scrip). These allotments were parcels of 160 or 240 acres in designated locations. Frequently, these lands were situated far from where families had lived or were subpar portions of scrub and swamp unsuitable for farming. Unwanted land certificates were then traded or sold for a fraction of their value to unscrupulous land speculators. Countless Métis relatives were left landless and destitute. Disenfranchised families began living on ten-foot-wide strips of land alongside roadways and other infrastructure; easements offering space for canvas tents and shacks of salvaged wood. These strips offered a tiny piece of earth with some south exposure to grow a garden, perhaps. This loss of hearth and homeland rendered the kitchen garden ever more vital.

In the spring of 1870, a steamboat passenger travelling from Missouri passed smallpox onto some Crow traders who then passed it to the Peigan. The sickness quickly spread throughout what is now known as Alberta. By the summer of 1870, thousands of people had died. The mortality rate was especially high for Métis and Indigenous populations. By July-end, the first smallpox case was reported at Fort Edmonton. Two-thirds of the community’s population became ill and over 300 perished.

While everyone tended to the sick and dying, the gardens grew amuck. Rows went unweeded. Rebellious cabbages shot their flowered bolts toward the sun. Ranks of trellised green beans went unharvested, drying stiff on the vine. The knotweed, mustard, and unruly lambsquarter found sanctuary amongst the cultivated. Purple stars of wild thyme hid in the shadow of uninvited grasses, herbaceous of all sorts that sprouted along the foot rows shook their downy heads of seed into the breeze while no one was looking.

The wave of disease passed by Fall, but a second outbreak moved through Lac Ste. Anne in October. The lakeside mission that regularly supplied Fort Edmonton with fish and vegetables lost one in ten of its citizens. To make matters worse, a large buffalo camp was caught in a prairie wildfire. Many carts and tents loaded with the winter meat supply burned where they stood. The Fort Edmonton chief factor reported 3,544 deaths that calendar year, not including those who perished of malnutrition or starvation. For those that survived, the stash of withered seeds gathered by forward-looking horticulturalists augured the reappearance of hope and plenty in the spring of 1871. The land and the garden would continue to provide.

In spite of famine due to the loss of the bison, and despite western disease and disenfranchisement, the Métis People endured. Their misfortunes met with a signature cooperative spirit, sharing music and homegrown food through dark days of want. Perhaps Métis parents felt a measure of relief calculating the future yield of the kernels held lovingly in their hands. Maybe there would be enough cabbage, enough bushels of beets to trade with other families, or to sell at the roadside stand. Enough for another pot of soup, with boullettes to celebrate a new year. The garden teaches us about gratitude, that “enough is a feast”, as my mother says. In dark times, go to the garden.

Read In Dark Times, Go to the Garden: Part 2

Jenna Chalifoux © 2021