The summer of 2010 was a memorable time: I started dating my future husband, and I started exploring Edmonton’s river valley trail system. It turns out, from the perspective a born-and-raised Edmontonian, a good first date is taking the girl you like, who is new to Edmonton, on the beautiful nature trails the city is famous for. I was stunned that city residents have access to such an expansive stretch of nature! Just a few minutes after entering a trail, the city just disappears. I felt engulfed in nature, from the dirt pathways to the trees. On certain trails by the river’s edge, seeing the river and dense forest was a sight to behold.

One day, while on a trail around Sir Wilfred Laurier Park near the Valley Zoo, I saw this crumbling set of cement columns by a steep cliff across the North Saskatchewan River. I asked my boyfriend, “what is that?” He said, “That’s the End of The World.” I suspected it was more of a nickname than a formal name, but it felt fitting. I was learning about different attractions in the city, like Fort Edmonton Park, the Art Gallery, and couldn’t recall the End of The World being listed.

We saw people trying to walk as close to the edge as possible. I can imagine that standing on that cement ledge would feel like you were on the edge of the world, looking out at a vast horizon a view that would be majestic. It did not occur to us to visit then, but in our future walks along the river valley, I happily pointed it out whenever I recognize it.

View of Keillor Point, from across the river at Laurier Park. Photo credit: Corey Grajkowski, November 2020.

A digital map satellite view of Keillor Point location from Google Maps, captured in November 2020 by the author.

What is now colloquially known as “The End of the World” was, at one point, part of Keillor Road. It ran from Fox Drive, located at the bottom on the valley, up to a stretch of Saskatchewan Drive in the Belgravia neighbourhood and is located at the top of the river valley at 7433 Saskatchewan Drive NW.

The road was named after Dr. Keillor, a medical officer during World War I. He purchased the land in the area in 1918 after it was repossessed from John Walter, who lost his fortune in a 1915 flood. Keillor farmed on the river valley flat and, after his death, the city purchased the land for $250,000. This area became the location of the Whitemud Equine Centre. In 1995, due to the high costs of maintaining the road in need of continuous repairs to ensure the stability of its pillars and foundation, the city held a referendum, and the road was closed.

In the fall of 2002, a landslide took out Keillor Road and the associated trail system, leaving behind the short platform and pillars now known as the End of the World. Due to the height of these structures and the absence of any safety railing, the area was fenced off by the City and entrance to the area was prohibited. Signage to deter trespassing was erected and people who visited the End of the World were ticketed by police officers.

To access the End of the World one would walk down a well-worn but steep footpath through the trees from Saskatchewan Drive. You arrive on to the flat platform (the size of a catwalk), where you can have stable footing to take in the view and take pictures. For the brave of heart, you can choose to sit down on the platform and let your feet dangle, looking down at the 5 meter drop below. For those even more daring, one can work their courage to step on to the very front of the catwalk, right on the front column that is visibly starting to crumble.

Countless blogs, news articles, and social media posts describe the motivations of visitors as well as how they felt upon visiting this hidden gem in the city. End of the World was so popular that it was recognized by location apps like Google Maps. Some Edmontonians made an annual ritual of visiting the site, to conquer their fears and take in the view to help uplift their spirits. People invited visitors from different provinces and countries to proudly showcase this stunning vantage point of the city, to talk about the history, and to locate nearby attractions that can be seen from the site, such as Fort Edmonton Park and the Valley Zoo. People take pride in showcasing locations that are considered to be hidden gems.

The location also became a communal secret for some youth to go to an exciting location and smoke or have a few drinks, and for some, as an underground location to go for a party. Countless photoshoots had used this location to document life milestones such as engagements and weddings. The seclusion and the physical challenge to get to the site provides additional appeal to some visitors. Being able to proclaim that one has conquered their fears and gone to the End of the World held a strong appeal.

The increase in visitors caused some concerns for the residents along Saskatchewan Drive whose homes were by the location’s entrance. Residents were concerned about litter, noise from activity at all times of the day and night, and the occasional accidents caused by someone falling down. One night, gunshots were fired from there with the bullets allegedly landing in a home in Windsor Park, understandably escalating concerns of residents.

As a result, the Belgravia Community League, spearheaded by Roger Laing, formed the Belgravia Community League’s End of the World Committee to address these issues. In a news article the group was quoted as stating that a goal of the renovation is to “drive away the vandals by inviting the public.”

Post-renovation entrance to the End of the World. Photo credit: Corey Grajkowski, November 2020.

View of the river valley cliff from the platform at Keillor Point, previously known as the ‘End of the World.’ Photo credit: Corey Grajkowski, November 2020.

I had a conversation online with a fellow Edmontonian who passionately advocated against the renovations that were proposed.

I was vocally against the changing and ruination of the End of the World by the City of Edmonton, spearheaded by a wealthy neighbourhood that didn’t want “outsiders” to visit. There was never a serious injury on site. There was some vandalism and other sorts of light “law breaking” like drugs, but there was never any serious issues ever reported during the time it was the End of the World. Instead, you would go and see wedding parties taking photos. You would meet up with the “troublesome teenager element” you’d be warned about by the neighbours and they would tell you stories and offer you some weed. It was a communal secret that people would share and it was lovely.

Unfortunately, the city decided to destroy that beauty and in the interest of “safety” cut off the interesting parts of the End of the World and made it into a rather benign lookout point, now known as Keillor Point. We took something beautiful and unique to our city and decided to pre-emptively destroy it, because we were worried about the “what ifs”, despite years of no major issues being reported.

Unfortunately, the neighbours around the landmark championed to destroy it and won after all. I don’t go visit that spot anymore and don’t tour people around to it. So they got their wish, less people visiting it.

The city determined that renovations ought to be done to ensure safety for a location that was frequently visited but is potentially precarious in terms of its condition. Beginning with public engagement in 2015, and some design work was done in 2016. In 2018, stairs and railing were installed, and then in 2019 was the finishing touches with the installation of a granular trail and landscaping. The name “Keillor Point” was officially recommended by the City’s Naming Committee and adopted by City Council to capture the history of the location.

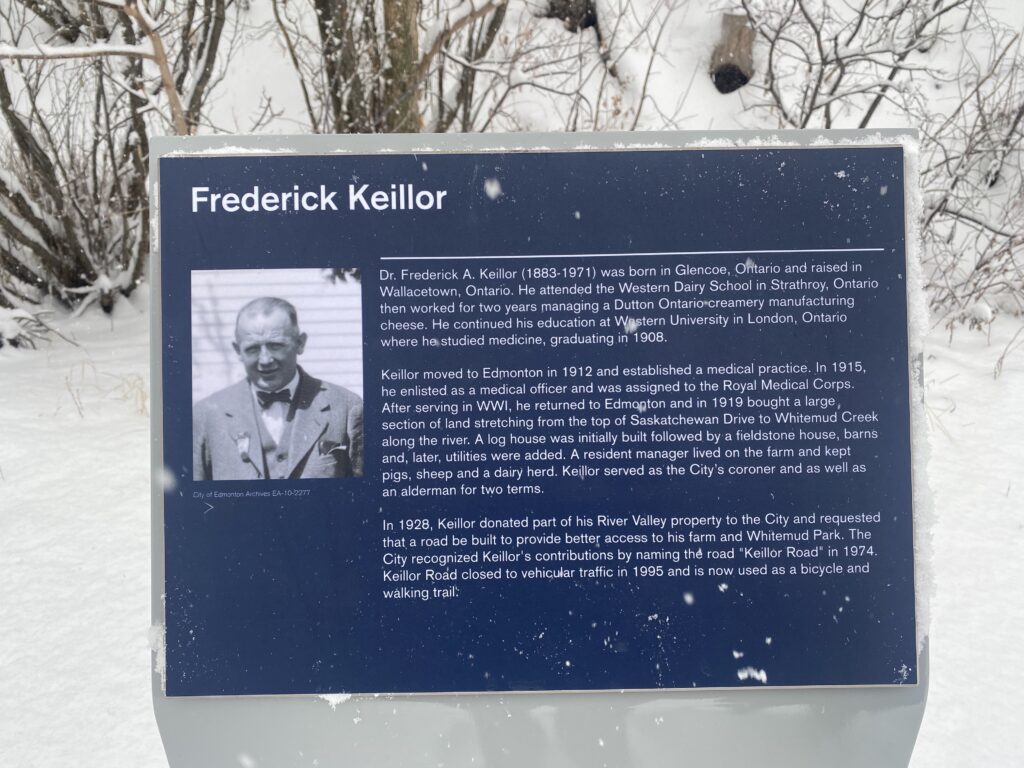

This plaque was installed as part of the renovations of the Keillor Point. It is located at the bottom of the wooden stairs. Photo Credit: Giselle General, November 2020.

Trail sign directing people to Keillor Point. Photo Credit: Giselle General, November 2020.

In November 2020, my husband and I finally decided to visit Keillor Point. It was a very snowy day, fresh snowflakes heaping on sidewalks and roads. The directional sign by the entrance to the site felt like a greeting, with a style similar to other parks and trails of the city. I could not imagine visiting this place in the winter if the pathways, wide sturdy staircase, and the railings are not there. For Edmontonians who are blessed to have an expansive nature trail and river cutting the city in half, viewing points that are dotted over the city are treasured. Similar to the Funicular and the Touch the Water project, there is an increasing awareness that access to the river valley ought to be more inclusive, which can be a motivation to the renovation of the location. The view of the river from Keillor Point, in all of its winter glory, is still a sight to behold. I brushed off the snow on the plaque that outlines the history of the location and we took in the view together.

The opportunity to be in a location to take in the vastness of nature is a universal human sentiment. This is why, for Albertans, going out camping and hiking places like Elk Island, Banff, Jasper and Canmore is a frequently sought-after activity. It is also why many enjoy traveling to other countries and visit oceans, deserts and forests. It would sometimes take hours or days to let modern life fade away even just for a while and rest our spirit, mind and body. With our river valley trail network, and unique vantage points like this, we Edmontonians get a chance to do this, in a more convenient fashion.

Giselle General © 2021