Edmontonian Hilwie Hamdon (née Taha Johma, 1905-1988) was a community leader and founding member of the historic Al Rashid Mosque, the first purpose-built mosque in Canada. Her leadership in the Arab and Muslim communities of Edmonton was critical in establishing the Ladies’ Muslim Society, a civic-minded group of women that organized numerous social and fundraising events to support aid efforts both at home and abroad. Hilwie Hamdon’s work with the Al Rashid Mosque and the Ladies’ Muslim Society is an integral part of Edmonton’s history of community activism and faith-based initiatives from the 1940s to the 1960s.

Turmoil and Change: Greater Syria and Arab Migration West

By the time Hilwie Hamdon was born in 1905, the Middle East faced a number of significant socio-political changes. Her ancestral village of Lala in the Beqaa Valley was still part of a region known as ‘Greater Syria’ (Bilād al-S̲h̲ām), a region that had been part of the Ottoman Empire since 1516.[1] While the region included people of a range of ethnicities and religions, they would often be referred to as being Syrians, or at times, the misnomer ‘Mohammedans.’ However, this would soon change after the colonial period when borders were redrawn and nation states emerged. With the end of French Mandate rule in 1943, the country now known as Lebanon is where Hilwie Hamdon came from.

As the result of the turmoil leading up to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in 1914, along with widespread famine, many families like the Hamdons left their villages and towns for a sense of stability and better economic prospects.[2] The uncertainty of the period caused many to migrate to North and South America. For example, some 20,000 immigrants left the Eastern Mediterranean and traveled to the United States between the 1870s and the 1930s. Another 220,000 migrated to Central and South America for destinations such as Argentina and Brazil.[3]According to historian Baha Abu-Laban, by 1901 there were approximately 2,000 people of Arab origin in Canada and by 1941, the population had grown to 11,857 people.[4] The Arabs who settled the Canadian Prairies, “operated general stores, bakeries and cafes in towns throughout the West and some were traveling merchants, visiting the isolated farms on foot or by horse and wagon in summer, and sleigh in winter.”[5]

From Lebanon to Canada: A Fort Chipewyan Arrival

In a 1964 interview with the Edmonton Journal, Hilwie recalled how she arrived to Fort Chipewyan wearing a full-length fur coat that her new spouse, fur-trader Ali Hamdon, had purchased for her – one that was ultimately too big, but would soon be necessary for her new life in northern Alberta.[6] With Ali by her side, Hilwie had set sail on the Queen Mary from Beirut to New York City before making the arduous journey north to Fort Chipewyan by train and riverboat up the Athabasca River in 1922.[7]

Remarkably, the voyage Ali Hamdon undertook to the Beqaa Valley in 1922 to visit family, and ultimately find a spouse, was also documented in the Edmonton Journal. In the interview, Ali describes how he boarded a ship from New York City, sailed to Southampton UK, and then to Egypt where he then traveled through Palestine by car until he reached Beirut.[8] Ali spent a year abroad before returning to Canada with Hilwie to settle in Fort Chipewyan, whereupon they first lived in a backroom of their store for several years before moving an eight-room frame house with their six children.[9]

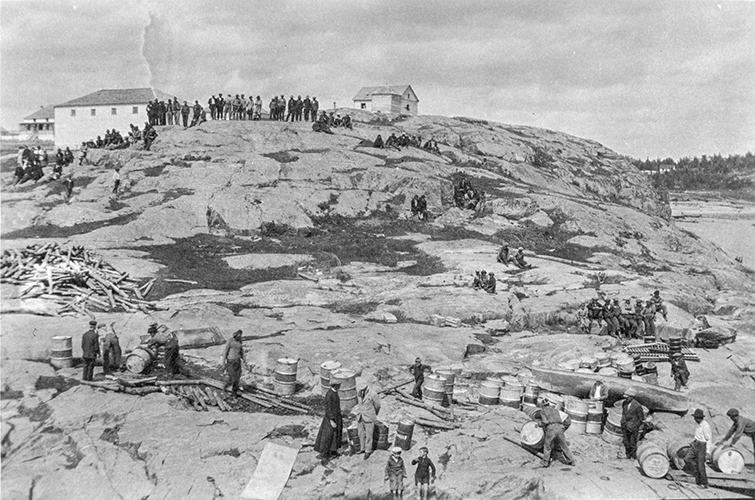

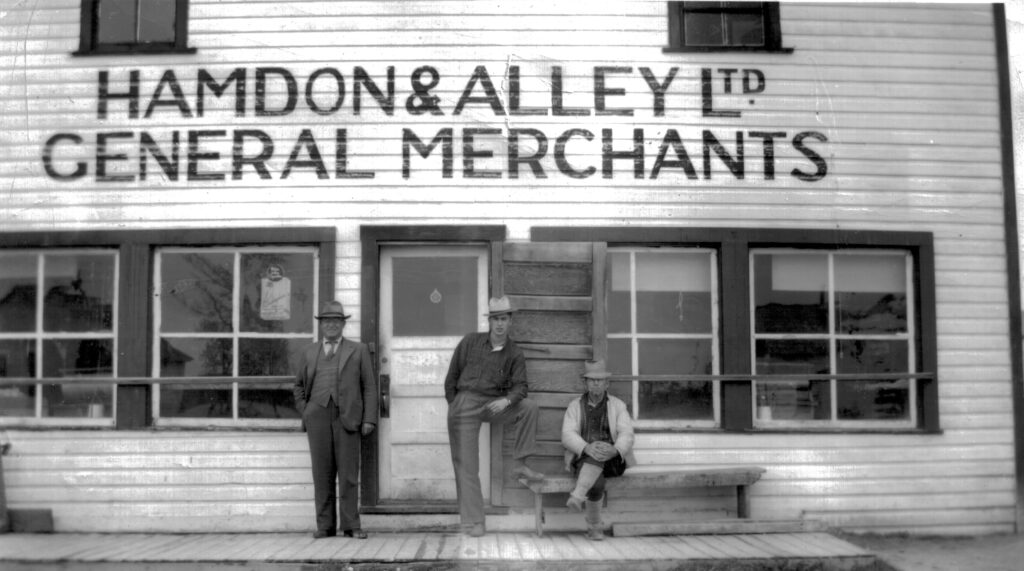

On the traditional territories of the Dene, and later the Cree and Michif, Fort Chipewyan (colloquially known as ‘Fort Chip’) was a trading post set up by the Northwest Company in 1788. Now part of Treaty 8, it was the site of intense, extractive trade, land and resource struggles between the Northwest Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company for several decades.[10] From the 1920s-1940s, Ali Hamdon was an independent fur-trading merchant who owned and operated Hamdon & Alley Ltd. in Fort Chipewyan, with additional posts in Fond-du-Lac and Black Bay Saskatchewan. During their early years in Fort Chipewyan, the Hamdons were among the few non-European immigrants in the predominately Indigenous community, and their livelihood in Canada were deeply dependent on the fur-trading economies of northern Alberta.[11]

Raising the Al-Rashid Mosque

With her children steadily growing, Hilwie decided to move to Edmonton in order for them to pursue educational opportunities and to connect with Arabs in the city. Upon settling to Edmonton in 1933 on her own and with her young children in tow, Hilwie quickly made connections with other Arab families by regularly organize gatherings in the city.[12] The Hamdon home soon became a place for hot meals and social connections, particularly for newly arrived bachelors from the Middle East.

While the Hamdon home was a frequent gathering place, according to Hilwie’s son Sidney, the establishment of the Al Rashid Mosque is what became one of her crowning achievements.[13] By the 1930s, the growing Arab Muslim community needed a larger space to congregate, and in early 1938, a group of Muslims approached Edmonton Mayor John Frye for help. Hilwie quickly became the group spokesperson and convinced the Mayor for the city to donate the land to build the mosque on. Funds were raised through numerous dinners and teas, but also by direct donations from individuals and families throughout Alberta and Saskatchewan, including many Christian and Jewish Arabs.[14] Built in 1938, the construction of the Al Rashid Mosque was the result of Prairie-based grassroots efforts.

Not simply limited to the practice of Islamic rituals, the mosque would provide women like Hilwie the space to have an active role in the social and community life of Muslims in Edmonton. While the first floor of the mosque was dedicated to communal prayer, the basement was the site of numerous multi-faith and multi-ethnic social gatherings.

Teas, Dinners and Bake Sales: The Organizational Efforts of the Muslim Ladies’ Association

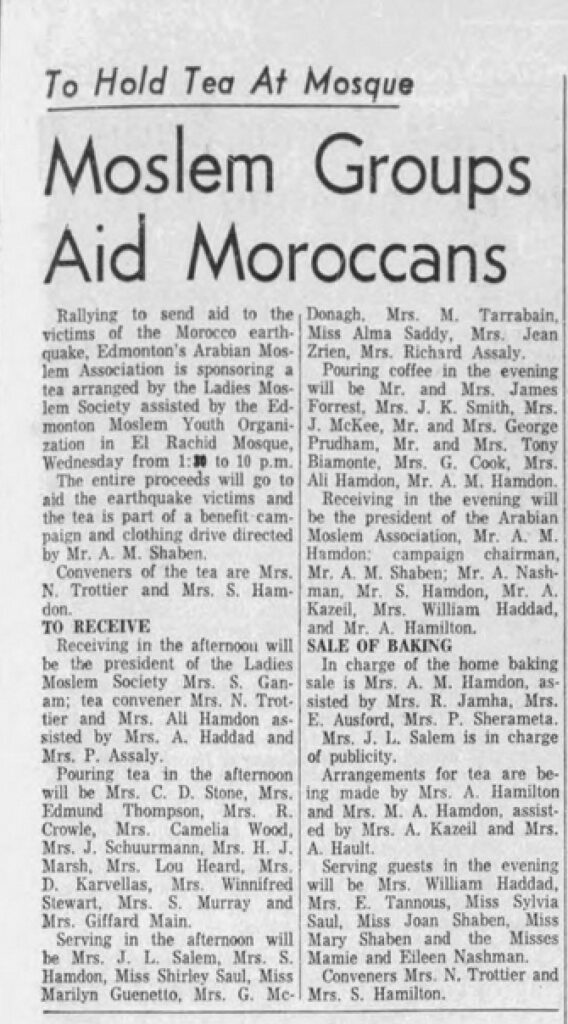

A large part of the Al Rashid Mosque’s early history is the Ladies’ Muslim Society, a group of community-oriented women who organized teas, dinners and bazaars to fundraise for the creation of the mosque. Their activities however were not limited to the mosque; the group regularly organised a number of initiatives to support a broad range of social and humanitarian efforts. From sending supplies for WWII efforts to increased resources for school children in Edmonton, the women would regularly organize public events and place ads in the Edmonton Journal. For example, in 1960 the Society organized a tea fundraiser for the relief efforts for the Agadir earthquake of 1960. The daylong coffee and tea event raised awareness, clothing and funds for one of Morocco’s largest natural disasters that saw a death toll of 12,000 people.[15]

Moreover, these social events would also introduce the larger public to the foods and customs of the Middle East. As one of the primary cooks for the events, Hilwie would make foods such as the meat and grain dish known as kibbeh, Syrian bread (khubz ‘arabee) and meat pies (fateyar) for hundreds of people at a time. Reflecting on Arab life on the Canadian Prairies, writer Habeeb Salloum notes that “it was a struggle for first generation Syrian immigrants to express and preserve their culture by preparing their daily meals” primarily because many ingredients for recipes were difficult to obtain.[16] Numerous recipes would need to be adapted using ingredients found locally, however they would still maintain the culinary richness of their forebearers.

Among some of the significant members of the Association were Hilwie, along with her daughter-in-law Faye Hamdon, Rikia Saddy, and Justine Kazeil Troittier. In addition to serving as the President of the Muslim Ladies’ Association Hilwie was one of six charter members of the Al Rashid Mosque, which also included: Miriam Darwish, Rikia Saddy, Miriam Teha, Vera Samuel Jamha and Margaret Ali El Hadjar.[17] For many years, these women were instrumental in both the fundraising and the social life of the mosque.

A Continued Legacy: The Hilwie Hamdon School

In recognition of her contributions to the City of Edmonton and to the Arab and Muslim communities, the Edmonton Public School Board named a school after Hilwie Hamdon in 2017. The school, which focuses on kindergarten to Grade 9, is one of four public schools in Canada currently named after a Muslim woman. The school’s philosophy is one that envisions that “students becoming responsible, ethical and respectful global citizens” – an ethos that echoes Hilwie’s own lifelong personal values.[18]

“She was deeply inspirational as a woman of faith, but without dogma,” remembers Hilwie’s granddaughter Dr. Evelyn Hamdon. Guided by her faith, Hilwie sought to create community and a sense of belonging amongst the numerous early Arab and Muslim settlers who made Edmonton home. Today, the Muslim community has grown and diversified, and the impact of community organizing and mutual aid remains. Hilwie Hamdon and the work of the Ladies’ Muslim Society serves as a reminder of the history of collective organizing and is a critical part of Edmonton’s history.

Nadia Kurd © 2021

[1] Provence, Michael. The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005), 5. “Greater Syria” included Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Palestine and Bilād al-S̲h̲ām was “a powerful construct, corresponding to term ‘Greater Syria’ which was often used in early 20th-century diplomatic and political parlance.” (https://archnet.org/authorities/6633)

[2] For more on the famine, see the online exhibition, “The Syrian Protestant College and the Great War (1914-18),” http://online-exhibit.aub.edu.lb/exhibits/show/wwi

[3] Khater, Akram. “Phoenician or Arab, Lebanese or Syrian ~ who were the early Immigrants to America?” Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies website. Accessed 30 December 2020. https://lebanesestudies.news.chass.ncsu.edu/2017/09/20/phoenician-or-arab/

[4] Abu-Laban, Baha. An Olive Branch on the Family Tree: the Arabs in Canada (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart), 1.

[5] “Old Stock Canadians: Arab Settlers in Western Canada.” Sarah Carter. October 1, 2015. ActiveHistory.ca. Accessed 30 December 2020. https://activehistory.ca/2015/10/old-stock-canadians-arab-settlers-in-western-canada/

[6] Ruth Bowen, “Beirut to Chipewyan,” Edmonton Journal, May 12, 1964, 13.

[7] Hamdon, Sidney. “Hilwie Hamdon,” Edmonton In Our Own Words, Goyette, Linda, and Carolina Jakeway Roemmich, eds. (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2004), 161.

[8] “Took Risks for His Wife: Braved Bandits on Syrian Trip,” Edmonton Journal, July 23, 1923, 5.

[9] Mohammed Hamdon, interview with the Author. January 9, 2021.

[10] “Fort Chipewyan.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, edited March 4, 2015. Accessed 30 December 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fort-chipewyan

[11] In 1927, Chinese immigrant Charlie Mah opened the Athabasca Café (Mah’s Cafe) in Fort Chipewyan. See: https://serenamah.com/f/women-of-inspiration-my-mom-the-mentor

[12] Sidney Hamdon, 296.

[13] Forster, Merna. 100 More Canadian Heroines: Famous and Forgotten Faces (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2011), 162.

[14] Interview with author.

[15] “On this Day, 1960: Thousands dead in Moroccan earthquake,” BBC News, Accessed 30 December 2020. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/february/29/newsid_3829000/3829809.stm

[16] Salloum, Habeeb, Leila Salloum Elias and Muna Salloum. The Scent of Pomegranates and Rose Water: Reviving the Beautiful Food Traditions of Syria (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018), 18.

[17] Awid, Richard. Through the Eyes of the Son: A Factual History about Canadian Arabs (Edmonton: Accent Printing, Ltd. 2000), 72.

[18] In an interview with the author, Hilwie’s son, Munir (Mo) Hamdon points out that when his mother came to Canada, she could not functionally read or write in either Arabic or English, which made the school naming particularly poignant. “School Philosophy,” Hilwie Hamdon School. Accessed 30 December 2020. https://hilwiehamdon.epsb.ca/aboutourschool/schoolphilosophy/