The owner of any historic home will wonder about the generations that have lived within its walls. When I recently moved into a 1914 foursquare in the Westmount Architectural Heritage District, the city of Edmonton encouraged me to research the first occupant of my house, Alfred Carrothers, in return for a historic plaque.

As the father of young children, and an educator myself (I recently moved to Edmonton to teach history at MacEwan University), I was heartened to learn Carrothers was the Manager of the Alberta School Supply Company. This was a firm, one commentator noted, that carried on “most commendable work in the wholesale handling of school supplies,” including “Preston Ball-Bearing Desks,” “Acme Plate Blackboards,” and “‘Hero’ ventilating room heaters” (crucial on frigid winter days in one-room schoolhouses).[i]

Carrothers was also a family man. Born in Ontario in 1883, he married Edith Avarne Walkeden of Birmingham, England, in Regina in 1908. The two then settled in the booming frontier-town and new provincial capital of Edmonton. Here, they filled their new home with three sons, as well as occasional boarders, usually female schoolteachers, amid Edmonton’s boomtime housing shortage. Every morning, Carrothers boarded the streetcar on Edward (124th) Street to get to his offices downtown. His children stayed home with Edith. They were still too young for the brand-new Westmount School, a grand brick edifice on the city’s marshy western edge. Amenities and convenience likely lured the Carrothers in the same way they attracted my family to the neighbourhood over a century later.

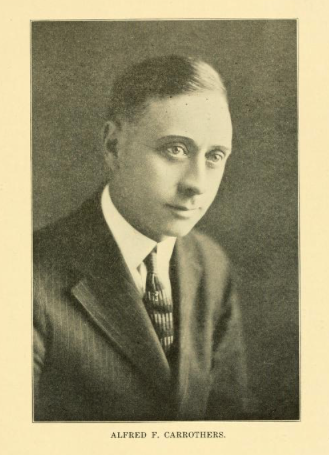

As time passed, Carrothers’ business dealings diversified. A biographical sketch in the 1924 publication Alberta, Past and Present, offers a striking photograph, and describes Carrothers as one of the “leading investment bankers of the city,” who had “made good use of his time, talents and opportunities” in the “general supply business” and as the stockholder of coal companies in both Britain and British Columbia. The entry assures its readers that Carrothers, “alert, energetic and determined,” a “strong Conservative in his political views” and a “Methodist in religious faith,” was “essentially a member of the class of doers, gifted with initiative and quick resolve.” His success, the article concludes, was “the result of unabating industry, self-confidence and a readiness to assume responsibility.” In sum, Carrothers was an archetypal success story, the type of pioneer businessman our province, rich in minerals and in reverence for entrepreneurs, likes to celebrate. But is this boosterish 1924 biography to be believed? If its final lines seem overblown—“he is highly regarded in business circles and has many friends, whose esteem he has won and retained by reason of his high principles and fine personal qualities”—it may be because they concealed a darker truth. Carrothers’ tidily combed hair and measured pose projected confidence and resolve, but his sideways glance betrays a yawning insecurity, an imperiled future, and an already guilty conscience.[ii]

In photographs, Carrothers tilted his head to the left, perhaps to conceal a birthmark, listed as a distinguishing feature in a 1935 immigration document debarring him from entry into the United States. Image of Alfred Carrothers from Alberta, Past & Present (1924), p. 229.

Anyone reading the New York Times on July 2, 1918 would learn that Carrothers, having left his young family in Edmonton, had been living for nearly a year in the luxurious Waldorf Astoria on New York City’s 5th Avenue (the hotel’s original location was later demolished to make way for the Empire State Building). It was here that Manhattan authorities, in coordination with Canadian police, arrested Carrothers for “securing money by false pretenses” and extradited him back to Edmonton.[iii] For this provincial notable turned would-be-mogul, life in the Big Apple no doubt appealed (horrendous hotel bills notwithstanding!). Court records, however, suggest he was in New York to evade justice. In 1916, the Alberta Attorney General started amassing evidence Carrothers had been borrowing money, in sums exceeding $350,000 (more than $5 million today), against the credit of fraudulent debentures issued by the Alberta School Supply Company. Carrothers may have needed the money to fulfil contracts to purchase cattle in Mexico, or to recoup lost money from Russian Imperial Bonds, which he had been trying to resell months before the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. Whatever the case, witnesses from rural Alberta school districts, some of them new immigrants with limited English-language abilities, testified they had entrusted their finances to Carrothers, whose slick and confident demeanor convinced them to unknowingly sign forged documents. Carrothers claimed it had all been a misunderstanding, but he soon fled the country—an implicit admission of guilt that likely influenced his conviction and six-month prison sentence delivered in December 1918.[iv]

Whatever his claims of personal rectitude, Carrothers’ 1918 Manhattan arrest was part of a larger pattern of white collar criminality. Following his release—even as Alberta Past and Present published its negligently unvetted biography—Carrothers pursued new schemes, illegally selling prefabricated lumber houses, and forging signatures in order to receive his business partner’s mail, possibly with the prurient desire to read details of a marital affair. For these new offenses, Carrothers escaped jail time. But he was not so lucky in 1928, when Edmonton police raided his office, now in the CPR building on Jasper Avenue, following nearly a dozen public complaints.[v]

Carrothers, then the manager of Columbia Rivers Saw Mill near Valemount, BC, had placed multiple newspaper advertisements offering applicants a salaried job in return for a personal investment, ranging from $250-$500 ($3800-$7500 today) “as a security you will take an interest in the business.” Carrothers, however, pocketed the investment and never delivered the promised job. The Mill, though a real concern, had ceased operations the previous year when lumberjacks went on strike for unpaid wages. Those who fell for Carrothers’ scam were often marginal or unemployed. One victim, a ward of the Neglected Children’s Department, confessed his bewilderment that Carrothers would want to hire him without any experience. In each case, to gain their confidence, Carrothers presented contracts (expired, as it happens) for rail ties from Canadian National Rail, along with a “book called Alberta Past and Present, which contained a write up on A.F. Carrothers.” A copy was seized by police and presented as evidence at the trial. “He showed me a book Whose Who [sic] in Alberta,” one witness testified, “and his picture and name was among prominent men of Alberta…to prove his standing.”

By this time, a recidivist like Carrothers exhausted any remnants of leniency. If Alberta Past and Present had boasted of his “many friends,” a letter from his own lawyer complained Carrothers “owes us a lot of money” and noted the defendant had “practically no friends, certainly none who will put up any money for him.” Struggling to make bail, Carrothers spent much of the trial in jail—there was no escape to New York this time. Ultimately, Justice Walsh (the same judge as in 1918) sentenced Carrothers to three years in the Prince Albert penitentiary, the maximum possible sentence. His cell walls must have been a bleak contrast to the wide open spaces, full of promise, that he had encountered when he first moved to the prairies some twenty years prior.[vi]

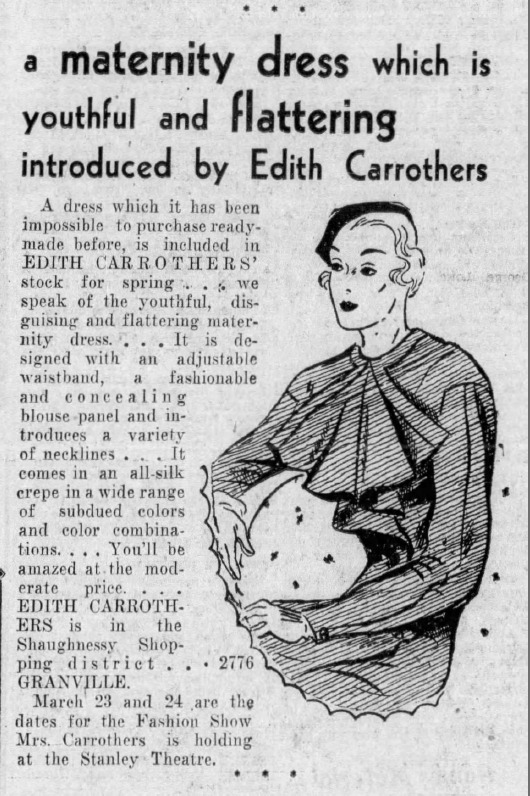

How did such antics impact Carrothers’ wife and children, who first made my Westmount house a home? Edith likely reconciled with her husband after his first arrest (they were, at least, still living together during the 1921 census). By 1931, however, they were estranged, and in 1935, Carrothers travelled with a 21-year-old blonde, probably on a romantic elopement, to the Vance Hotel—a prominent Seattle landmark, the Pacific Northwest’s equivalent, perhaps, of the Waldorf Astoria. Carrothers, however, was detained by US Immigration and denied entry, no doubt owing to his arrest and extradition in 1918.[vii] Edith, meanwhile, had moved to Vancouver with her sons, where she opened a successful ladies’ wear shop in the Granville fashion district, which became an enduring institution specializing in “distinguished gowns and suits.”[viii] Edith’s sons also appeared by this point to have disavowed their father—he was conspicuously absent from their wedding announcements, and the eldest dropped his legal name, Alfred, in favour of his middle names, Tennyson Avarne, the latter honouring his mother.[ix] Though Edith’s life did not generate the same legal paper trail as her husband, she successfully petitioned a court to have Alfred declared “officially dead” in 1945. Summer 1936 was the last time she had seen him alive—shortly before yet another arrest and conviction.[x] Though Alfred actually lived until 1962, Edith’s new status as a widow allowed her to collect life insurance—a reminder of the precarious social and financial situation of single women in early twentieth-century Canada.

Alfred Carrothers was attracted to Alberta’s prosperity and opportunity. Yet his downfall reminds us of the corruption that often accompanies the quest for easy money. In his Alberta Past and Present biography, parts of which he likely dictated himself, Carrothers cashed in on the mythology of the self-made man, of the resourceful, independent “class of doers” transforming the frontier with capitalism and civilization. The success he did achieve, however, rested, in part, on his abuse of public institutions—the Alberta school system, government rail contracts—and on a series of confidence tricks against Edmonton’s less fortunate—immigrants, the unemployed, the credulous, and his own wife and children. And though the legal system eventually caught up with him, it let him off for too long: back in 1918, Justice Walsh lamented the law “provided a fourteen year sentence for a horse thief” but less than a year “for crimes such as Carrothers ha[d] committed.”[xi]

Over the past century, my house has been renovated many times, but it still retains its original charm. When I imagine its first occupants, residents of Edmonton’s newest rather than oldest neighbourhood, I prefer to remember Edith rather than Alfred. Her hard work, resourcefulness, and personal and economic recovery offer a more edifying early chapter to the house and city I now call home.

Aidan Forth © 2021

[i] Archbishop Emile Joseph Legal, Short sketches of the history of the Catholic church and missions in Central Alberta (Winnipeg: West Canada Publishing, 1914), p. 160.

[ii] John Blue, Alberta, Past and Present: Historical and biographical, Volume 2 (Chicago: Pioneer Historical Publishing, 1924), pp. 228-231.

[iii] “Arrest of Canadian Broker. Alfred Carrothers Held Here on Request of Edmonton Police,” New York Times, July 2, 1918. Local news also reported the arrest: “Alfred F. Carrothers Stands Trial on Charge of Securing $20000 by False Pretenses,” Edmonton Journal, December 18, 1918.

[iv] Provincial Archives of Alberta, GR1983.001 5034 Box 55; GR1983.001 6899A, Box 78; Fort Saskatchewan prison ledger GR1979.0139 item 305, p. 171.

[v] Provincial Archives of Alberta, GR1983.001 Box 143, GR1972.0026 6742/C, Box 107.

[vi] Provincial Archives of Alberta, GR1983.0001/5907 Box 157; GR19840067, File C/442,Box 261.

[vii] He also appears to have lied about his age. National Archives, Washington DC, Manifests of Alien Arrivals in the Seattle, WA District, A4107, Roll 7.

[viii] “Week-end fashions for young cosmopolites,” Vancouver Sun, May 23, 1936, p. 13.

[ix] “Carrothers-Baxter Nuptials Thursday,” Vancouver Sun, June 23, 1933.

[x] “Former Broker Presumed Dead,” Vancouver Sun, November 1, 1945; “One Years Term for Business Broker,” The Daily Province, July 24, 1936.

[xi] “Carrothers gets Six Months in Provincial Jail,” Edmonton Journal, December 21, 1918.