Royal Beginnings

Coronation Park is a 35-hectare park in west central Edmonton. It was named to honour Queen Elizabeth II’s 1953 coronation. For its small size compared to others in the city, the park — a gem of green space in the heart of the city — has many historically significant sites. One of those is the one-of-a-kind Queen Elizabeth II Planetarium, the first one in Canada.

Like the park it’s in, the planetarium has a royal connection: it commemorates the July 1959 visit of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip. Then-Mayor William Hawrelak stated, “In commemoration of this Royal Visit… we respectfully request of your Majesty’s permission to name this building the Queen Elizabeth II Planetarium. In your presence today we humbly demonstrate our allegiance, our gratitude, and our affection.”

On September 22, 1960, then-Mayor Elmer Roper presided over the dedication and opening of the planetarium. Alberta Supreme Court Chief Justice C.J. Forward read a congratulatory letter from the Queen’s Secretary. University of Alberta professor E.S. Keeping presented a 68-pound fragment of the Bruderheim meteorite, which had crashed to Earth in March that year. The rock became the centrepiece of the planetarium’s astronomy display.

Bold Design

Team members from the City Architect’s Office, including Walter Telfer, Richard Falconer Duke, and Denis Mulvaney, designed the planetarium in a modern expressionist style. The building is the central focal point of Coronation Park, and it represents the crown jewel in the Queen’s sceptre. Aerial photos of the area show how the park’s pathways form an outline of a sceptre.

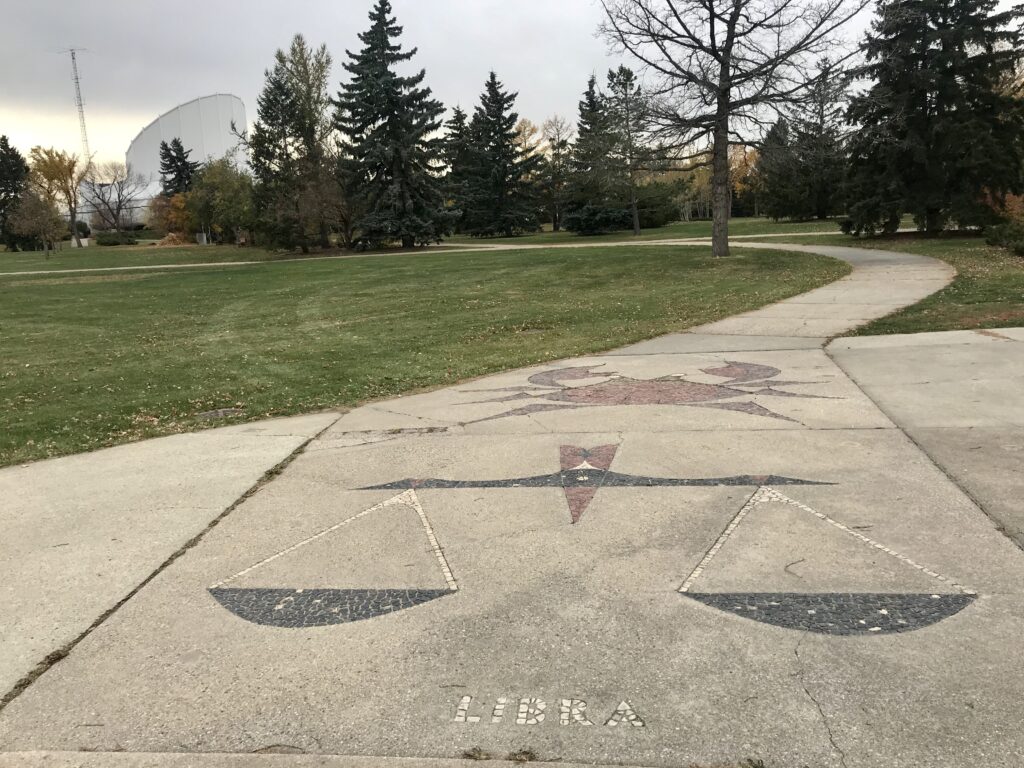

The building’s distinctive structure resembles a hovering spaceship. It has a curved front exterior, floor-to-ceiling windows with gold-coloured frames, and an eight-metre dome. The dome was originally orange but was later painted silver. The front patio features the twelve astrological signs represented by inlaid stone mosaics that artists Edith and Heinrich Eichner created in 1966.

Premium Programming

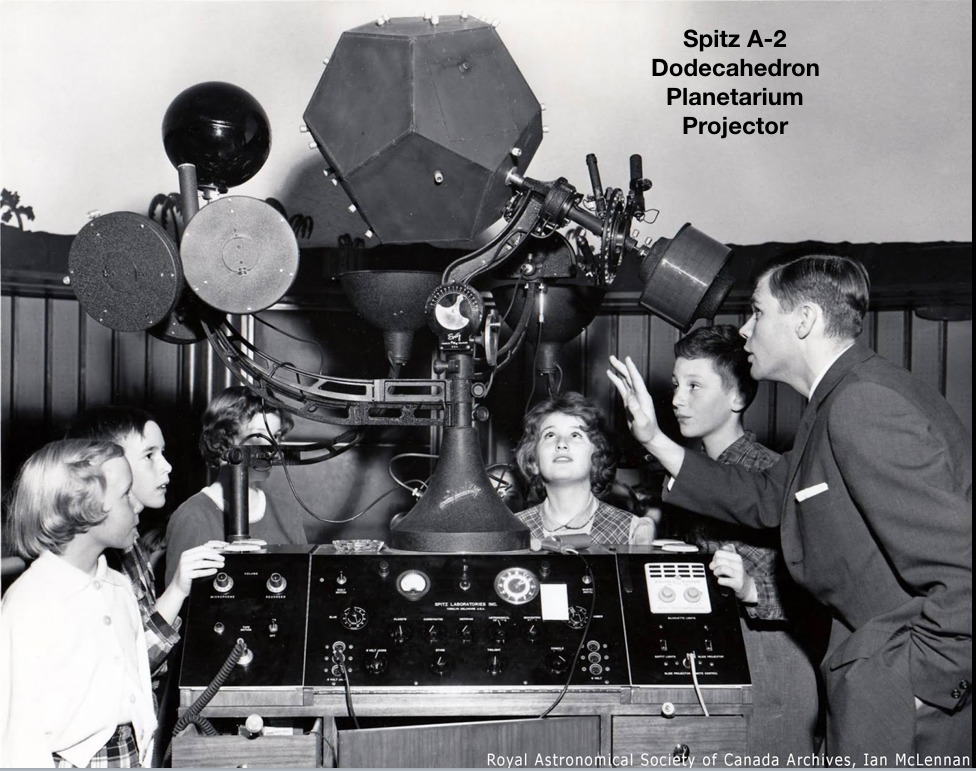

Ian McLennan, who worked at CFRN Radio and Television at the time, had helped the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Edmonton Centre lobby City Council in 1958 to build the planetarium. Council approved the project in March 1959. As the opening date neared, J.W. Wright, Director of Parks and Recreation, asked McLennan to be the founding director. McLennan says it was “the proverbial offer that could not be refused.” As part of his duties, he worked with his team to create the astronomy and night-sky presentations, where staff projected images of planets, stars, and constellations onto the dome to educate and entertain visitors.

Although never in a planetarium before then, McLennan used show production basics from the TV industry to create these shows. “At the encouragement of the mayor of Edmonton at the time (Elmer Roper), I took a tour of several major planetariums in the USA. That’s when I discovered (to my amazement — and even horror) that we were doing more sophisticated programming in the QEP… [which] began to attract world-wide attention from others in the planetarium profession.”

Planetarium staff were dedicated to high-quality programs. They conceptualized, scripted, and developed shows with special effects and auxiliary projectors to enhance viewer experience; they even commissioned unique music and art. Some programming was themed to special astronomy events. For example, McLennan says, “I flew to NASA-JPL in Los Angeles to intercept the images coming back from one of the first Mars exploration spacecraft, Mariner IV. We couriered the close-up images of Mars… back to the planetarium.”

Community Response

Although initial interest in the planetarium was low, word of mouth about the new experience began to spread and, as McLennan says, “it became a must-see for many in the public realm — and then a very popular destination daily for school classes.”

Once the community discovered what the planetarium offered, it became a much-loved venue. McLennan says that he still talks to people, such as noted architectural critic Trevor Boddy and science writer Christopher Gainor, who “recall with great fondness attending Queen Elizabeth Planetarium as young students. They, and others, have very specific memories of being dazzled by the wonders of the universe — a memory that has lasted the better part of a lifetime.”

The Lull in the Middle

According to the Edmonton Historical Board, the planetarium’s popularity peaked in 1967, with 33,500 visitors that year. On December 31, 1983, it closed to the general public because the Edmonton Space and Science Centre (now TELUS World of Science – Edmonton) was due to open elsewhere in Coronation Park in 1984. From 1984 until about 2000, the science centre ran science and computer camps out of the building. In 2001, some science centre equipment and staff were moved over there because the main science centre needed more space.

Masood Makarechian was one of the staff members who moved there at that time. He worked on the Science in Motion team that toured the province providing science education to K – 12 schools in areas 100+ kilometres outside Edmonton. They used the space for office work and the dome for practicing the star shows that they delivered to schools. Makarechian first became aware of the planetarium when he went there on a field trip in junior high. Looking back on when he became a staff member, he recalls thinking, “‘Hey, I was in this building before; I remember being here once.’ And that instantly created that connection, like ‘I came here as a student. Now I’m here as a teacher.’”

When Science in Motion returned to the main science centre in the early 2000s, the former planetarium languished empty and unused and slowly fell into disrepair.

Inner Workings

Because the Queen Elizabeth II Planetarium has been closed to the general public for so long, many Edmontonians know only its signature exterior. McLennan says that in the building’s early days, its unique design provided an attractive work space. Large southern-exposure windows provided plenty of light, but they also caused problems with exhibits that needed light control. He also says, “We learned that public washrooms should never be placed right next to a star theatre. The ill-timed sound of a toilet flushing doesn’t enhance the quiet, dignified contemplation of a beautiful, rotating galaxy!” To reduce noise, they later padded the theatre doors.

Makarechian says that in some ways working there with the Science in Motion team in the early 2000s was “kind of like going to the Paris Opera… there’s beautiful stone on the walls and a bust of Copernicus… on a marble base, and you sort of feel like you’re in this fancy… building. And then there was the sense of decay… this is falling apart a little bit and not being taken care of, and [I felt] a little bit of sadness around that…. It felt like this is an abandoned jewel.”

Modern-Day Revival

In 2017, the City of Edmonton designated the planetarium as a municipal historic resource, which it defines as any “built structure, object or cultural resource… that is primarily of value for its history, architecture, urban context and integrity.” The designation was one of several steps that paved the way for a new era for the planetarium, one in which it sparkles once more as the crown jewel in Coronation Park.

Based on guidelines from the City and from Parks Canada’s Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada, the planetarium has been renovated and upgraded. TELUS World of Science – Edmonton and the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Edmonton Centre had input into the design. The renovation honours the heritage importance and uniqueness of the exterior by restoring those elements to their original condition or, if original materials cannot be kept, by simulating their appearance. The project also enhances the building’s interior and includes the following changes:

- insulation, repairs, and repainting the original dome (to gold)

- new mechanical equipment and LED lighting to meet current sustainability standards and building codes

- wheelchair-accessible, non-gender-specific public washrooms for visitors to the planetarium and the surrounding park

- mosaic renewal (expected in 2021)

In a 2019 Transforming Edmonton web article, Darren Giacobbo, City of Edmonton Program Manager with Facility Infrastructure Delivery, said, “In 1960, the original dome hosted its first show and now here we are today, 59 years later, restoring this historic building for future generations.” [Watch the progress of the dome restoration here.]

David Murray, an Edmonton conservation architect who was part of the restoration team, wrote in an article for On Site Review in 2020, “This building has defied the odds that have destroyed so many mid-century modern buildings. … This is one modern-era building that remains relevant and has proven to be sufficiently robust to indefinitely continue its role as nourishment for the imaginations of our children.”

The newly renovated Queen Elizabeth II Planetarium — scheduled to open in fall 2021 — will support the City’s Coronation Park Master Plan. It will reinvigorate and enhance the park and provide a new community gathering place leased to and operated by the TELUS World of Science – Edmonton. Its President and CEO Alan Nursall says their business plan includes facility rentals, summer camps, preschool programs, and future dome show production. “It is a great asset for the community and for the science centre, and we look forward to welcoming the community back to the QEP and celebrating its remarkable place in our city.”

Relevance Beyond Edmonton

The relevance and historical value of the Queen Elizabeth II Planetarium reach well beyond Edmonton. Alan Nursall says it “is a landmark of city‐wide importance given its long‐standing community role, unique high-quality design, and historical associations. As the first public planetarium in Canada, the building also holds national significance. … We are thrilled to be able to help bring it back to life.”

Since Ian McLennan’s early days as the planetarium’s founding director, he has become an internationally known and respected planetarium expert. In February 2021, Edmonton City Council approved the renaming of the planetarium access road in Coronation Park to Ian McLennan Way. Of the venue’s past, present, and future value to our community, McLennan says, “the Queen Elizabeth Planetarium — which started as a very modest suggestion to commemorate the Queen’s visit to Edmonton in 1959 — has had an effect on the world of science centres and planetariums far in excess of its modest beginnings, or even its modest scale…. The long-term influence QEP has had on the museum and science centre field, world-wide, is far beyond anything any of us could have dreamed in the early 1960s.”

Tracey Anderson © 2021

Header photo: The Queen Elizabeth Planetarium, 1970. Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives, EA-320-1.

References

Capital Modern Edmonton. 2012. Edmonton Planetarium Coronation Park — 1959. http://capitalmodernedmonton.com/buildings-by-area/edmonton-planetarium/ retrieval date Jan. 11, 2021.

City of Edmonton. October 29, 2008. Policy to Encourage the Designation and Rehabilitation of Municipal Historic Resources in Edmonton (C450B).https://www.edmonton.ca/city_government/documents/PDF/C450B.pdf. Retrieval date Oct. 8, 2020.

City of Edmonton. September 24, 2019. Far Out: Canada’s First Planetarium Being Restored to Former Glory. https://transforming.edmonton.ca/far-out-canadas-first-planetarium-being-restored-to-former-glory-2/ retrieval date Oct. 5, 2020.

City of Edmonton. n.d. Queen Elizabeth II Planetarium Restoration. https://www.edmonton.ca/projects_plans/parks_recreation/queen-elizabeth-planetarium.aspx retrieval date Oct. 5, 2020.

Edmonton Historical Board. n.d. Queen Elizabeth II Planetarium.https://www.edmontonsarchitecturalheritage.ca/index.cfm/structures/queen-elizabeth-ii-planetarium/retrieval date Sept. 20, 2020.

Edmonton Historical Board. n.d. Robert Falconer Duke. https://www.edmontonsarchitecturalheritage.ca/index.cfm/architects/robert-falconer-duke/ retrieval date Oct. 5, 2020.

Murray, David. 2020. On Site Review: 36: Our Material Future. Queen Elizabeth II Planetarium. 44-47.

TELUS World of Science – Edmonton. March 2, 2021. International Expert in The Planetarium Field Has Edmonton City Road Named After Him. https://telusworldofscienceedmonton.ca/learn/international-expert-planetarium-field-has-edmonton-city-road-named-after-him/. Retrieval date April 7, 2021.