It’s 2003, early in the new millennium but regrettably late in the story I’m aiming to tell. Doris Tanner died in 1997, and all the women who registered as architects before her are gone as well. In their absence, I reach out to others who may have known her – retired architects and engineers, clients, friends – anyone with memories to share.

Perspectives

“Doris Tanner. What did she do?” Bernie Wood asks the question that soon becomes a recurring theme in my quest. He turns to fellow architect Gordon Forbes during a visit to his retirement home in Edmonton, hoping for insights.

“Well, Doris,” Gordon says. “The only thing I know she did was one I was involved in originally: the Air Force Association clubhouse up on Kingsway.” He describes helping the 700 Wing RCAF Association plan and raise funds for the building, only to see Doris Tanner chosen as architect. The memory of being passed over for that job still brings a note of irritation to his voice: “If you’re going to do something for nothing, don’t expect to get anything back.”

Architects and engineers who’ve retired from Edmonton to balmy British Columbia also have trouble recalling much about Doris Tanner, but over coffee in Victoria’s inner harbour a few projects surface. “She designed Ebenezer United Church, quite a unique structure out in the west end,” says engineer Percy Butler, who also recalls some “nice modern” houses. “But she never really got into big work.”

“Doris’s own house on the south side was a notable design,” architect Bob Bouey offers. Talk turns to Doris’s husband the alderman (as city councilors were called at that time), and Bob describes social events where “we would tell Doris our problems, hoping she would whisper to him.”

Ebenezer United Church, completed in 1964. Image provided by the author.

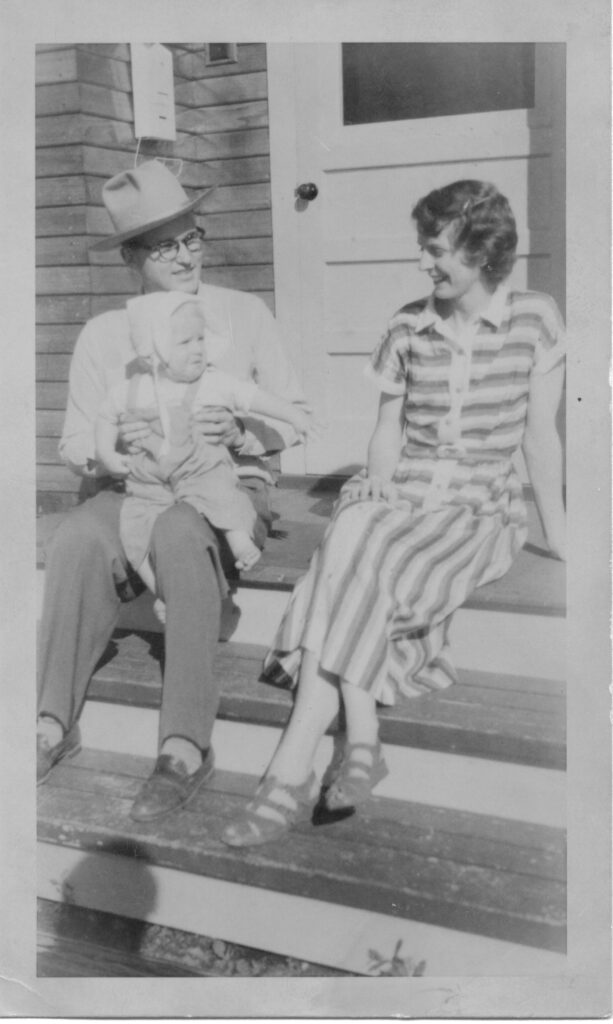

Four early female architects amid the men at 1948 AAA AGM – second row fr left Margaret Findlay, Mary Imrie, Doris Tanner front row Jean Wallbridge. Image provided by the author.

Back in Edmonton, retired engineer Henry Kasten has clearer memories, having worked on some Tanner projects. “Doris was an interesting case of a lady architect,” he says. “She must have taken her architecture about the same time as [Jean] Wallbridge and [Mary] Imrie, but she kind of vanished from the architectural scene because she – she became a housewife. She married Ches Tanner, and she raised a pack of kids. But you could tell that she knew her stuff about architecture.”

If Doris Tanner had been a man, I wonder, would the scope of her work spring more readily to mind?

Connections

Whether or not her pack of kids stunted Doris’s architectural career, their very existence opens another avenue of investigation. Archival searches for family connections turn up information about her father, Hubert Newland, who introduced progressive ideas as the provincial Superintendent of Schools. About her husband Ches, a chartered accountant, businessman and farmer as well as an alderman. But little else surfaces until Edmonton architect Vivian Manasc mentions knowing Merrill, one of Doris’s four children.

I first meet Merrill and her sisters, Susan and Laura, at the home office built in 1957 by and for Mary Imrie and Jean Wallbridge, who ran Canada’s first all-female architectural firm. I soon realize it’s a return visit as the three describe playing in and around this modern bungalow perched high above the North Saskatchewan River while their mother talked shop with “Mary-and-Jean,” who melded into one entity in their young minds. Now they see similarities to their mother’s designs in this space, from the large bank of windows overlooking the river valley to purposeful built-in furniture.

It turns out that Doris, Mary and Jean worked together early in their careers. First, at Rule, Wynn & Rule Architects, where Doris was gaining summer experience while studying at the University of Manitoba. Then, at the City of Edmonton, where they were paid less than their male counterparts despite City Architect Maxwell Dewar’s attempts to secure a salary equal to their work. Doris’s civic projects included St. Joseph’s Separate School and an acoustically fine addition to Victoria Composite High School.

Doris and Mary pondered launching a partnership together around this time, but shelved that plan. Perhaps they were swayed by a letter from Doris’s mother advising that, although the duo “might make a good stab at it,” Doris would need to delay having children out of fairness to Mary – and “there is no advantage to be gained in postponing that job.” Mary teamed up with Jean instead, with Doris doing some work alongside.

Immersed

As her daughters reminisce, I’m struck by the passion Doris Tanner felt for the career most contemporaries say she merely dabbled in. Laura, who practices Buddhism, recalls describing meditation to her mother as “a single point of concentration – total absorption,” to which her Doris replied: “That’s what I do when I design.”

Athletic, brilliant in math, a gifted painter, blessed with a photographic memory and parental support, Doris had other options. In fact, she was offered a math scholarship but chose architecture instead – and persevered despite harassment from her University of Manitoba classmates, who were all male. Returning to Edmonton, she engaged in architecture her entire adult life, creating sleek, modern buildings warmed by generous use of wood and ample windows. “She never wasted an inch of space and could produce innovative and beautiful environments from very little,” Susan tells me. “And like any talented artist she was preoccupied with light, including passive solar heat.”

Construction sites drew Doris like a magnet, her children trailing behind. “It wouldn’t matter what other deadlines were happening, or what the sign said about no trespassing. Our mother would crawl over the fence and go inspect the entire site,” Merrill says, and first-born Susan adds “That’s why she always wore pants.”

Mothering

Doris continued to work after Susan was born in 1948, supported by her mother and a nanny. She followed Maxwell Dewar from City Hall into private practice the next year but left the firm after Jim’s birth in 1951, consumed by care for her colicky and sleepless son.

Seventy years later, I meet Jim in an Edmonton coffee shop just blocks from the Highlands home where Doris grew up. He credits time spent under and at his mother’s drafting board, tracing the world map and learning to use her tools, for a continuing interest in design. He also recalls reading Jane Jacobs at her insistence and discussing urban design issues together, gathering insights he’d later use as a council member in Foothills County, Alberta.

All four children describe a reserved, even introverted mother who encouraged them to be active, independent and creative. A mother who outlawed paint by numbers but made sure they had art supplies, musical instruments, a sandbox, help with fort building and a backyard skating rink. A mother who showed her love not so much in words, but in actions. “She was a strong believer in the healing power of a cup of tea,” says Laura, who studied architecture and now runs a design business.

Although Doris said raising children was more important (and more difficult) than her career, architecture remained her first love. In the mid-1950s, when her husband spent a year at M.I.T. as a Sloan Scholar, she studied acoustics and housing at nearby Harvard. From 1968 to 1977, when Ches served on city council, she drafted his speeches, designed improvements to proposed civic projects, promoted affordable housing, lobbied for underground light rail transit and marshalled evidence against that era’s version of a downtown sports Omniplex. She did far more than “whisper” in Ches’s ear, and she did it on her own terms.

Unique

In 1957, between the births of Merrill and Laura, Doris completed two houses that illustrated her talent for innovating on a budget.

The first house, designed for the Tanner family, had a roof that slanted from single storey to storey-and-a-half from side to side, providing a perfect perch for Santa’s sleigh at Christmas time. Located in Edmonton’s Belgravia neighbourhood, the home’s single-storey end held an (unusual for the day) open-plan kitchen and living area with a vaulted ceiling and expansive views to the backyard. Polished plywood walls and particle board floors, finished to resemble cork, provided the warmth of wood at low cost. Heat from a fireplace in the open area naturally rose to the tall end of the house, which held six bedrooms (three a half-floor up and three down) and two bathrooms.

Slant-roofed family home, completed 1957, present day, front view & rear view. Images provided by the author.

The home was a study in time- and space-saving detail. Bedrooms sharing a wall with the living area had sliding wooden shutters, which could be opened to offer snacks, deliver laundry or check in without going up or down stairs. A freestanding wall unit provided moveable storage space, with doors on one side and a flip-down table and a high shelf on the reverse. “Other kids would arrive home and find their mother had moved the furniture,” Susan says. “I would arrive home to find the walls had moved.”

Grounded

Doris’s daughter Merrill joins me in touring the second of Doris’s innovative 1957 houses at the invitation of Charlie Richmond, who purchased the home in 1980. Designed for Lee and Areta Green, it overlooks Fulton Ravine just east of Wayne Gretzky Drive. Built on grade (unusual in Alberta), its low profile and large gabled windows put inhabitants “right into the environment,” Charlie tells us, delighted by that effect. Light from three directions penetrates almost every part of the house, he adds. “So even in winter you don’t feel like you’re living in a cave.”

Clockwise from left to right: The backyard of the Green House in 2013. Interior of the Green House. Green house, 1957, overlooking Fulton Ravine – innovations include DuAl blocks. Images provided by the author.

For the walls, Doris used Du-Al blocks, large rectangles made from cement and wood shavings, then filled with cement onsite for added strength and insulation. The blocks came from a nearby factory, one of several joint ventures involving Lee Green and Ches Tanner. Other innovations, such as straw mat roof insulation, failed to withstand Alberta’s climate; in taking the measurements needed for respectful restoration, Charlie discovered precise and repeated use of just five dimensions. “I really learned to appreciate what was in your mother’s mind,” he tells Merrill. “There’s a certain genius to choosing a small number of dimensions and then exploiting that.”

Compact

In 1958, the year her fourth child Laura was born, Doris began working on contract for Canadian Engineering Surveys (CES). That partnership continued until 1969, bringing larger commissions such as the Mayfair Hotel, a residential high-rise in Yellowknife, packing plants across the prairies – and the 700 Wing recreation centre.

In 2004, Laura and I tour the 700 Wing building, which evolved into the Chateau Louis Conference Centre when the association’s fortunes declined. The 700 Wing’s loss was the chateau’s gain, says Nigel Swarbruk, conference centre general manager. Noting how the banquet rooms all converge at a spot near the entrance, he adds: “This is a beautiful building to manage because it’s so compact. You can be in any of the rooms in just a few steps.”

Recognition

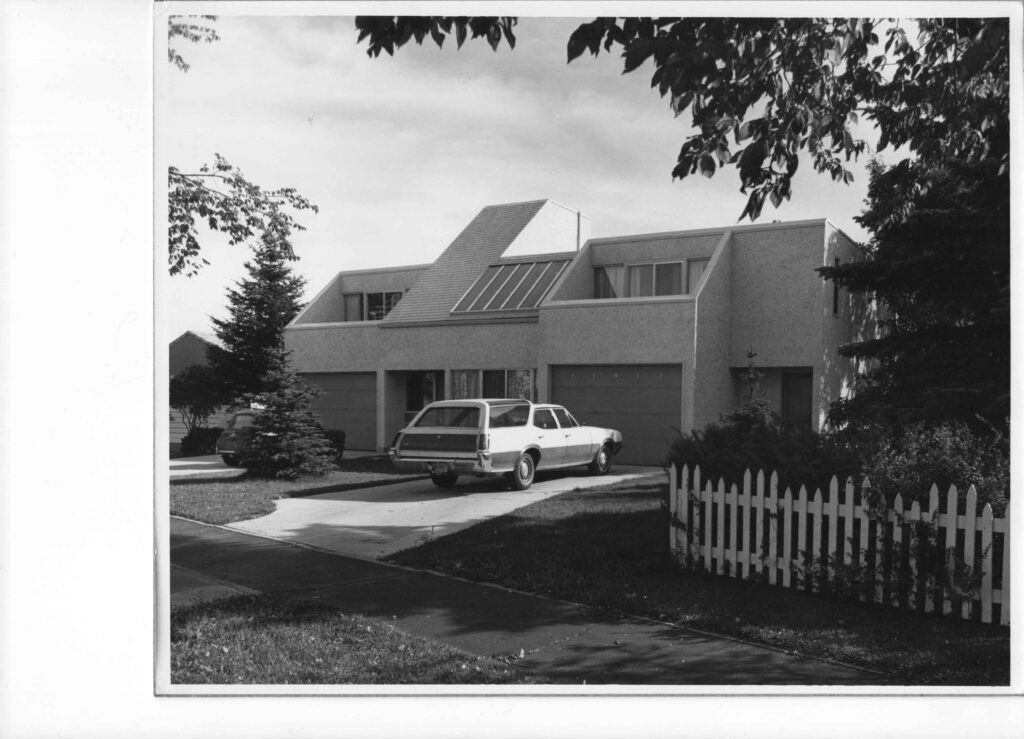

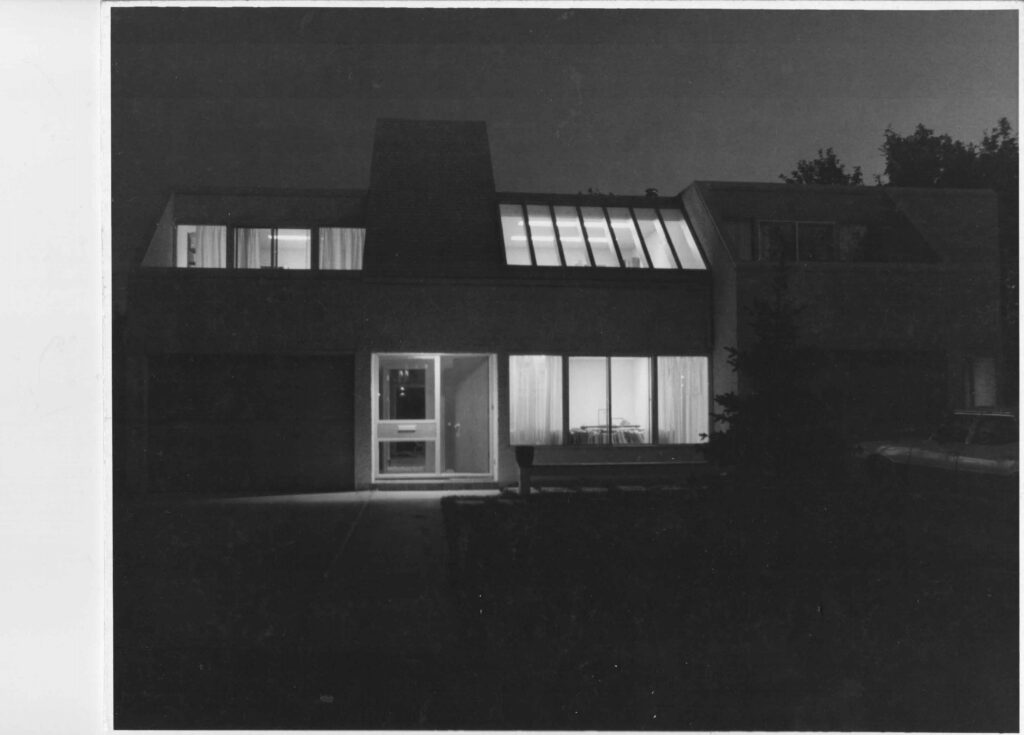

As her nest emptied in the early 1970s, Doris Tanner borrowed $100,000, purchased a lot just south of the University of Alberta and set about to kick-start a full-time solo practice by creating an innovative multi-family home. Numerous zoning issues later, her triplex beat out Hub Mall to win the 1974 Canadian Housing Design Council award for residential design. Two sections served as the Tanner family home and Doris’s office; the third provided rental income while demonstrating a way to integrate higher density into older neighbourhoods. To Merrill and Laura, who visit the compact yet airy space with me, it still feels like home.

Doris would later write that she entered the award competition as gender-neutral D.N. Tanner “so that no outside issues would arise.” Her handwritten explanation continues: “Impartial judgements of work done by women willencourage change in accepted creations.” The letter of congratulations she received was addressed to “Mr. Tanner.”

Despite such experiences, Doris objected when the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada requested input for an exhibit highlighting women in the profession. “It seems to me to be as discriminatory as ‘Blacks in American Architecture’ or ‘Jews in American Architecture,’” she responded. “Recognition should come from within the professions themselves – more judgeships, more fellowships, more women ‘Fellows’ of the RAIC.” She had no doubt women could prove themselves worthy. Architecture, she told her daughters, is just like sewing. “You simply make a plan, measure to fit, cut it out and put it together. Women do it all the time.”

Coda

In the next two decades Doris completed at least two dozen projects ranging from the Homestead Housing Co-operative to an expansive home for Tevie and Arliss Miller that, like Mary-and-Jeans’ home office, takes full advantage of its perch above the North Saskatchewan River. She continued working even when memory loss began limiting her capacity, at times with her daughter Laura’s support.

Inspired by their mother’s quiet, odds-defying confidence, Doris’s children also have juggled marriage and children with entrepreneurial careers. Like their mother, they cross-fertilize ideas and challenge convention, delivering outside-the-box solutions in such arenas as legal equality, voice and singing therapy, sustainable design and Indigenous/Aboriginal rights. In doing so, they honour a legacy that gives them great pride.

Cheryl Mahaffy © 2021

Miller house, view of rear from below. Image provided by the author.

Interior of Miller house, view from upper level of Tanner’s most elaborate residence. 1983. Image provided by the author.

Sources

Doris Tanner’s children – Susan, Jim, Merrill and Laura – for memories, photographs, clippings, letters and the loan of artifacts.

Charlie Richmond, current owner of Lee and Areta Green home, for sharing blueprints, vellums, time and information; his son Elison Richmond for photography; Harlan Green for joining a tour of the home his parents commissioned.

Other Tanner clients, including members of the 700 Wing, members of Ebenezer United Church of Canada and Arliss Miller, for sharing artifacts, memories, tours and time.

Former colleagues and friends, for their memories.

Amy von Heyking, “Selling Progressive Education to Albertans, 1935-53”. Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire De l’éducation, Vol 10, no. 1, May 1998, pp. 67-84 (doi.org/10.32316/hse/rhe.v10i1.1553), for information on Doris’s father as a leader in progressive education.