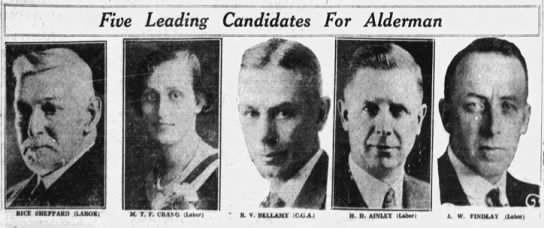

When Margaret Crang won a seat as an alderman in the 1933 municipal election, she set the record as the youngest person ever elected to Edmonton City Council—a record she holds to this day.[1] At just 23 years of age, Crang defied the predictions of “veteran civic campaigners who insisted ‘no woman will get into the aldermanic chair’,”[2] winning over 10,000 votes and coming in second place in a field of seventeen. Only the top five candidates won seats.[3]

On election night, the Edmonton Journal described Crang as “extremely quiet in personality” and “stunned by the news of her election.”[4] But it wouldn’t be long before Margaret Crang overturned that perception as well, becoming a loud and confident voice for social justice and anti-fascism both in Edmonton and around the world.

Margaret Tryphena Frances Crang was born in Edmonton—the only candidate in the 1933 election who could make this claim, as she was quick to point out.[5] She grew up in Garneau, with the Crang family home located where the University of Alberta Law Building now sits.[6]

Before her election, she was, in many ways, a stereotypical list-checking overachiever: a high school student with an outstanding academic record, a “dangerous competitor” in track and field events, and a “brilliant and influential member” of student executive committees.[7] She also fit the gifted-student archetype by fantasizing about remaking the world according to her own vision:

“As a young girl in my teens, I found myself rather addicted to spasms of conviction. Like all adolescent youth, I was given to the projection of desperate ideals of personal and social perfection. The fact is that I really believed that I had a mission to save the world, and what is worse, I knew exactly how the thing was to be done. I was out to mould the world in conformity with the heart’s desire.”

– Margaret Crang, “Where My Convictions Have Led Me”[8]

A picture of Margaret Crang from The Gateway, November 3, 1933. Accessed at: http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/GAT/1933/11/03/3/Ar00306.html

But she had one thing that most prodigies don’t: a father who had served as an elected official for more than two decades,[9] who raised her to participate in election campaigns[10] and who encouraged her to follow in his footsteps.[11] Crang credited her father not only for her precocious political acumen, but also for instilling the foundational values and ideology that would guide her career in public life—namely, as a self-identified “out and out socialist eager to see the present economic system changed into a socialistic state, that thousands of people now suffering might have a better lot in life.”[12]

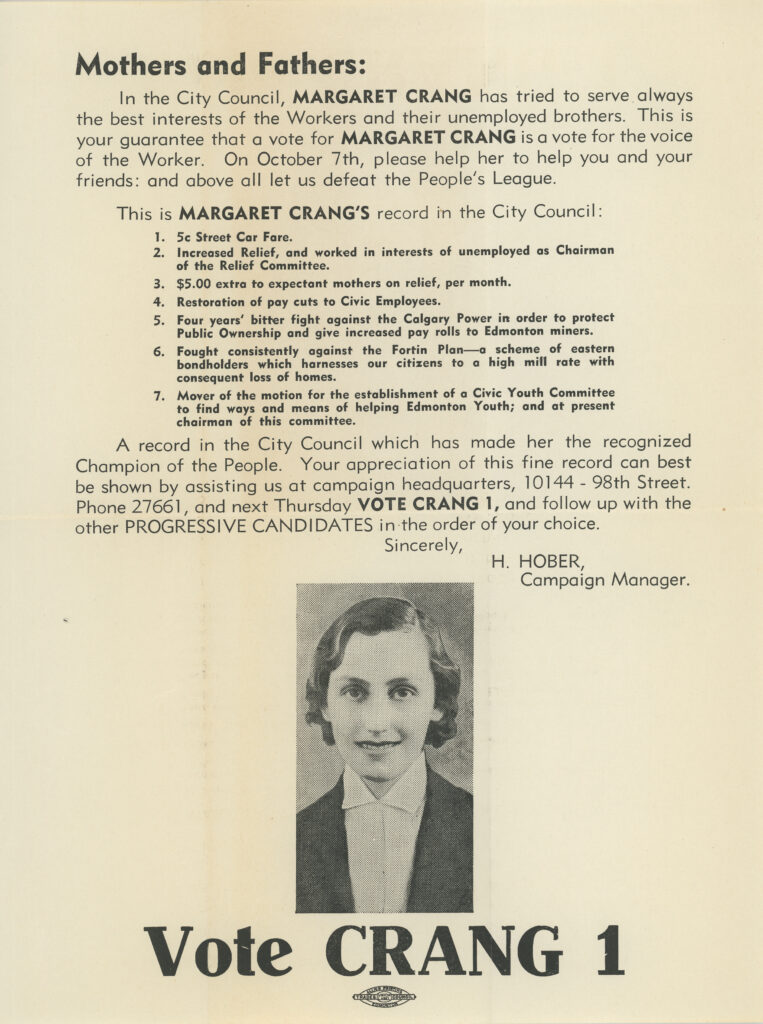

That conviction led her to run on a detailed platform of policy proposals, including everything from cash relief payments and medical attention for the unemployed, fair wages for civic employees, more resources for ex-servicemen, and appointing a woman to the relief commission.[13]

In her election and throughout her term, Crang didn’t try to downplay her gender, but highlighted it as a unique selling point. She spoke of “the dire need for representation that must have been felt by the women of Edmonton”[14] and evoked first-wave feminist thinking when she argued that “a woman can decide questions of better food and housing that come up in connection with relief better than a man.”[15]

Of course, she faced a constant headwind of benign, paternalistic sexism. Nearly all the reporting about her mentioned her attractiveness or what she was wearing, whether the actual story was about her first court appearance as sole counsel[16] or serving as “the youngest acting mayor in the history of Canadian cities.”[17]

But Margaret paid it no mind. She was too busy. Whether she was successfully pushing for a 5-cent streetcar fare and pay raises for workers[18] or threatening to resign from council if relief allowances to the unemployed were not increased,[19] Crang fought tirelessly for “the highest welfare of the laboring classes.”[20] She gave barnstorming speeches on “The Insanity of War”[21] and “The Menace of Fascism,”[22] declaring that war was the inevitable end product of capitalism[23] and advocating for an international strike of the unified working classes, should the rich and powerful try to force them to fight each other again, as they had in the First World War.[24] She criticized the two major parties (the Liberal/Conservative dichotomy was old even then) as two sides of the same elitist coin[25] and urged her progressive peers to get their proverbial sh*t together:

“We should take a more definite and concerted action on certain lines and show the people we are actively working for them. The people are looking for leaders and we should give them leaders.”[26]

When it came time for Crang to contest her second election, she dominated. Contrary to some reports, Margaret Crang wasn’t actually the first woman elected to Edmonton City Council—that honour goes to Izena Ross, who was elected in 1921 and served a one-year term.[27] But Crang was the first woman ever to be re-elected, and by a resounding majority; in the 1935 election, she took over 11,000 votes and came in first place.[28]

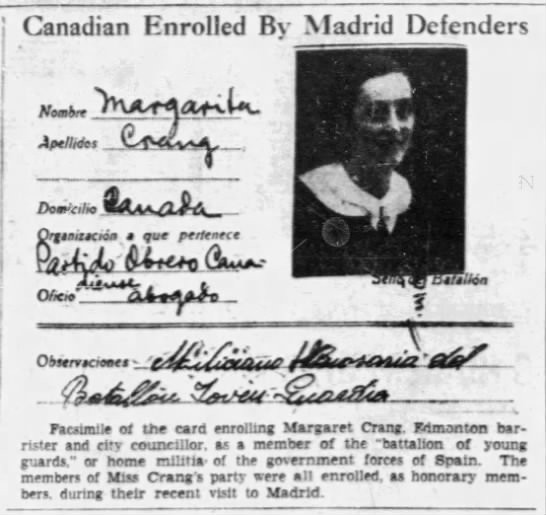

Her second term proceeded much as the first, with determined policies to improve the material conditions of her constituents and passionate denunciations of fascism. The latter led her to Europe in September 1936, where she participated in the Brussels Peace Congress and then snuck through a tunnel from France into Spain to get a first-hand view of the Spanish Civil War. Crang was an ardent supporter of the democratically elected government, and accurately predicted that “a Fascist win in Spain would mean a certain breakdown of the remaining democracies of continental Europe and would culminate in a world war.”[29]

To demonstrate her support for the government—and her solidarity with the milicianas, women as young as 17 who were fighting for democracy—while visiting the frontlines north of Madrid “she went up to the sandbag barricade and, borrowing a rifle, fired two shots for the government side.”[30]

When news of this got home to Canada, it sparked an outpouring of criticism in newspapers across the country. Crang was painted as a hypocrite who had betrayed her pacifist ideals[31] and was “unwomanly” for having taken up arms: “Spain may sink to whatever depths of degradation she chooses in employing her women as hired killers. But here in Canada we entertain a higher respect for our womenfolk,” harumphed a particularly agitated editorial.[32]

It’s debatable whether this short Spanish escapade lost Margaret Crang her seat when she ran for re-election in 1937—it was more than a year later, and Labor candidates were wiped out across the board, with not a single incumbent retaining their seat.[33] Crang was convinced it cost her a few votes,[34] and some historians have more baldly claimed that it “destroyed her political career.”[35] She made two failed comeback runs for a seat on city council, and had three unsuccessful attempts at becoming a provincial MLA, before washing her hands of politics.

Even out of office, she continued to be a voice for marginalized people—sponsoring the petition of the first Black woman who applied to be a nursing student at the Royal Alexandra Hospital,[36] defending the religious freedom of a persecuted Jehovah’s Witness in court,[37] and advocating fiercely for the rights of Chinese and Sikh immigrants.[38]

Crang eventually left Edmonton to work as a reporter for the Montreal Gazette. A diagnosis with Cushing’s syndrome led to physical impairments for much of her life, and she moved across Canada and the United States to seek treatment before ending up in Vancouver—an eccentric aunt in a “ratty old dressing gown” who grew marijuana on her windowsill.[39]

Margaret Crang only served on Edmonton City Council for four years. But her short tenure left a long legacy. Her firebrand advocacy had an impact on the space for women in politics—and not just in Edmonton. Midway through her second term, Crang was briefly mentioned in a Globe article about the “gradual intrusion” of women into municipal government across Canada. The only quote from a woman in this article is a female councillor saying, “I am going to sit and listen for a while, because I realize I have things to learn” with the paper noting that “her statement is indicative of the spirit of women in entering the new municipal sphere.”[40]

Margaret Crang was not that type of woman. She spoke her mind and fought for the principles she believed in, even if it ruffled feathers. She was a woman of “extraordinary pertinacity and nerve.”[41] She served with humility, but also with conviction. And she paved the way for generations of young women, just as she had hoped on election night in 1933, when she kicked open the door to City Hall:

“’Since this is the first time I have run for city office,’ she said that evening, ‘it is almost too much to expect to be elected… But if I have led the way for other women to take active part in civic affairs, I have accomplished one of my objects.’”[42]

Bruce Cinnamon © 2021

Note regarding the title: AOC refers to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Beginning in 2019 to present day, she is the United States representative for New York’s 14th congressional district. As of publication, AOC is the youngest person to serve in in the U.S. Congress.

[1] “CRANG, MARGRET [sic] TRYPHENE FRANCIS.” Biographies of Council Members. Office of the City Clerk, City of Edmonton, 5 November 2014. Accessed 23 November 2020. https://www.edmonton.ca/city_government/documents/Chapter_18_-_Biographies.pdf

[2] “Miss Crang Is Admitted Alberta Bar.” The Edmonton Journal, 5 March 1934, Page 2. NB: this quotation is curious, as Margaret Crang was actually the second woman elected to Edmonton City Council—the first being Izena Ross to a one-year term in 1921-1922.

[3] “Labor Scores Smashing Victory – Re-elect Mayor Knott, 4 Aldermen, 2 Trustees; Plebiscite Is Carried.” The Edmonton Journal, 9 November 1933, Page 1.

[4] “Miss M. Crang Hears Results.” The Edmonton Journal, 9 November 1933, Page 19.

[5] “Fire Opening Guns In City Vote Battle; Hecklers Are Busy – Civic Election Candidates Run Gauntlet of Hecklers As Opening Guns Are Fired.” The Edmonton Journal, 3 November 1933, Page 7.

[6] Margaret Crang fonds. Provincial Archives of Alberta. Accessed 23 November 2020. https://hermis.alberta.ca/paa/Details.aspx?ObjectID=PR0067&dv=True&deptID=1

[7] “For Secretary of Women’s Athletics – Margaret Crang, Arts ‘30, Law ’32.” The Gateway, 15 March 1929, Page 4. Accessed 23 November 2020. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/GAT/1929/03/15/4/Ar00401.html

[8] As quoted in “Intriguing, exasperating, extraordinary; City’s youngest elected official will finally have her name on a little piece of Edmonton.” Paula Simons. The Edmonton Journal, 15 June 2013: E.1. Accessed 23 November 2020.

https://www.pressreader.com/canada/edmonton-journal/20130615/283158606189045

[9] “Family Seeks Civic Honors – Dr. F. W. Crang and His Daughter, Margaret, in Campaign.” The Edmonton Journal, 8 November 1933, Page 42.

[10] “Miss M. Crang Enjoys Clash – Youthful Candidate Champions Women on City Council.” The Edmonton Journal, 7 November 1933, Page 8.

[11] “Intriguing, exasperating, extraordinary; City’s youngest elected official will finally have her name on a little piece of Edmonton.” Paula Simons. The Edmonton Journal, 15 June 2013: E.1. Accessed 23 November 2020.

https://www.pressreader.com/canada/edmonton-journal/20130615/283158606189045

[12] “Dynamic `girl alderman’ is yet to be honored.” Jac MacDonald. The Edmonton Journal, 22 October 1989: B2.

[13] “Woman on Relief Body Advocated – Margaret Crang Wants Her Sex Represented on Commission.” The Edmonton Journal, 2 November 1933, Page 13.

[14] “Miss M. Crang Hears Results – Youthful City Councillor Is Overjoyed at Election.” The Edmonton Journal, 9 November 1933, Page 19.

[15] “Youngest councillor’s career in politics a casualty of civil war.” Trish Worron. The Edmonton Journal, 21 July 1996: F.1.

[16] “Miss Crang Makes Debut As Sole Counsel In Case – Slightly Nervous at Start But Quickly Gets Her Stride.” The Edmonton Journal, 18 June 1935, Page 9.

[17] “Capital Boasts Youngest Acting Mayor in Canada – Miss Margaret Crang Invests Chief Executive’s Position With New Charm.” The Calgary Daily Herald, 28 January 1935, Page 14.

[18] “Intriguing, exasperating, extraordinary; City’s youngest elected official will finally have her name on a little piece of Edmonton.” Paula Simons. The Edmonton Journal, 15 June 2013: E.1. Accessed 23 November 2020.

https://www.pressreader.com/canada/edmonton-journal/20130615/283158606189045 – See reprinted campaign pamphlet trumpeting Crang’s record on council.

[19] “C.L.P. Endorses Relief Increase – Ald. Crang Prepared to Resign if Boost Not Effective June 1.” The Edmonton Journal, 23 May 1934, Page 15.

[20] “Socialist State in Canada Ideal of Woman Alderman – Ald. Margaret Crang Tells Eastern Interviewer of Aims.” The Edmonton Journal, 10 June 1935, Page 2.

[21] “Miss Crang Luncheon Speaker.” The Calgary Daily Herald, 27 November 1935, Page 28.

[22] “Young Speaker Here Thursday.” The Calgary Daily Herald, 26 November 1935, Page 12.

[23] “Margaret Crang Discusses War At Luncheon – Calls Fascism Intensified Capitalism; Urges Women To Fight It.” The Calgary Daily Herald, 29 November 1935, Page 21.

[24] “Would Employ Strike Against Another War – Alderman Margaret Crang, Edmonton, Addresses Anti-War League.” The Calgary Daily Herald, 30 November 1935, Page 18.

[25] “Socialist State in Canada Ideal of Woman Alderman – Ald. Margaret Crang Tells Eastern Interviewer of Aims.” The Edmonton Journal, 10 June 1935, Page 2.

[26] “Labor Plans Drive For 1935 Election.” The Edmonton Journal, 28 November 1934, Page 14.

[27] “Intriguing, exasperating, extraordinary; City’s youngest elected official will finally have her name on a little piece of Edmonton.” Paula Simons. The Edmonton Journal, 15 June 2013: E.1. Accessed 23 November 2020.

https://www.pressreader.com/canada/edmonton-journal/20130615/283158606189045

[28] “Clarke Defeats Three Candidates in Civic Election – Ald. Margaret Crang, Labor, Tops Council Vote.” The Calgary Daily Herald, 14 November 1935, Page 1.

[29] “Science Club Hears Graduate on Spanish War.” The Gateway, 27 November 1936, Page 1. Accessed 23 November 2020. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/GAT/1936/11/27/1/Ar00105.html

[30] “Ald. Miss Crang Leaves Peace Parley To Fire Shots At Rebels Near Madrid.” The Edmonton Journal, 13 October 1936, Page 1.

[31] “A Peace Delegate With A Rifle.” The Ottawa Journal, 19 October 1936, Page 4.

[32] “The Lady Boasts.” The Vancouver Sun, 15 October 1936, Page 6.

[33] “’My God, are they sending women?’: Three Canadian Women in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939.” Larry Hannant. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, Vol 15, No 1, 2004. Page 168. Accessed 23 November 2020. https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/jcha/2004-v15-n1-jcha1027/012072ar.pdf

[34] “Dynamic `girl alderman’ is yet to be honored.” Jac MacDonald. The Edmonton Journal, 22 October 1989: B2.

[35] “Youngest councillor’s career in politics a casualty of civil war.” Trish Worron. The Edmonton Journal, 21 July 1996: F.1.

[36] “Negress to Start Training as Nurse.” The Calgary Daily Herald, 17 December 1938, Page 3.

[37] “Illegal Sect Member Fined.” The Calgary Daily Herald, 16 April 1941, Page 2.

[38] “Intriguing, exasperating, extraordinary; City’s youngest elected official will finally have her name on a little piece of Edmonton.” Paula Simons. The Edmonton Journal, 15 June 2013: E.1. Accessed 23 November 2020.

https://www.pressreader.com/canada/edmonton-journal/20130615/283158606189045

[39] Ibid.

[40] “Canadian Women Take Firmer Grasp of Public Affairs: Gradual Intrusion Into Municipal Government Evinces New Interest.” The Globe, Toronto, 3 January 1936, Page 10.

[41] “Alderman Crang.” The Gateway, 10 November 1933, Page 4. Accessed 23 November 2020. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/GAT/1933/11/10/4/Ar00401.html

[42] “Dr. Crang Slips, Falls, Sprains Arm – Labor Candidate and Daughter Remain at Home To Get Returns.” The Edmonton Journal, 8 November 1933, Page 42.

Further Reading:

Monto, Tom. Protest and progress: three labour radicals in early Edmonton. Edmonton: Crang Publishing, 2012.