Read The Last Black West: Oklahoma Freedmen Seek Refuge in Alberta, Part 1.

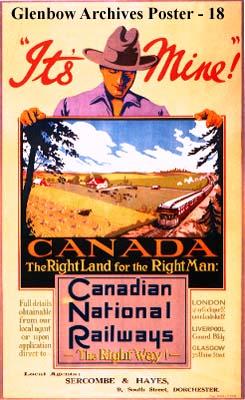

As we noted in Part 1, early 20th century western Canadian immigration propaganda had the unintended consequence of bringing a Black presence to Alberta and Saskatchewan. While the glowing stories about the “Last Best West” were targeted at white, Midwestern farmers, these ads had particular resonance with Black Freedmen from Oklahoma. With the discovery of oil, the land base of the Oklahoma Freedmen was under assault.

“It’s Mine! Canada – The Right Land for the Right Man. Canadian National Railways – The Right Way!” Canadian National Railways, circa 1920-1935. Glenbow Archives Poster Collection, accessed via Alberta on the Record.

The case of Sarah Rector demonstrates the particularities of a little-known but related moment in history. Rector was a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation whose land sat on a vast oil deposit sixty miles west of Tulsa. While newspapers proclaimed Rector to be the “first Black millionairess,” an NAACP investigation revealed that she was exploited by a court-appointed white guardian, who made himself rich managing Rector’s assets. Booker T. Washington and W.E.B DuBois raised awareness about Rector’s situation. While she found a safe haven in Kansas City, other Freedmen were not so lucky.

Freedmen are the descendants of enslaved Africans held by the Five Tribes in Indian Territory. Even if you know nothing about the particular African-Indigenous history of the Freedmen, you have undoubtedly felt their long-lasting cultural influences. From Slavery to Freedom, called the most “authoritative, definitive and comprehensive” history of African-Americans, was written by John Hope Franklin, a Chickasaw Freedman. The spirituals “Sweet Low, Sweet Chariot,” and “Steal Away to Jesus” (a favourite of Queen Victoria) were written by a Choctaw Freedman named Wallace Willis.[1]Freedmen were at the heart of Seminole life from Florida and Oklahoma. Freedmen often spoke two or three languages (a tribal language or two, plus English), sang Indigenous hymns, and cooked hybridized Euro-African-Indigenous food like cornbread and barbecue.

How many of the Black Pioneers of Alberta were of Freedmen ancestry? It is very difficult to know for certain. R. Bruce Shepard estimated that only ten percent had an Indigenous ancestor.[2] Harold Martin Troper’s research suggests that many more African-Americans had kinship ties to the tribes but would have kept that a secret in Canada. Alberta author and teacher Gwendolyn Brooks had Muscogee (Creek) ancestry, and she remembers some wealthy Creek Freedmen funding their relocation to Canada with money made from their Oklahoma allotments.

Black immigrants might not have disclosed connections to Indigenous nations in Oklahoma for a good reason: the federal government in their new home had been carrying out a genocidal campaign against First Nations. Furthermore, many Canadian government officials mistook Blacks for “Indians,” making them subject to the repressive policies of the Indian Act.

Frank Oliver, the Edmonton publisher who served as Minister of the Interior from 1905 to 1911, heard about a distinction between “State Blacks” and “Freedmen,” and became alarmed. Oliver sent an agent to Oklahoma to investigate the Black townships after receiving angry letters from the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire in Edmonton. “We view with alarm the continuous and rapid influx of Negro settlers,” the IODE wrote, “[this] immigration will have the immediate effect of… discouraging white settlement in the vicinity of the Negro farms and will depreciate the value of all holdings within such areas.”[3]

As nothing in the Immigration Act of 1906 specifically barred certain people on race, nationality, or ethnicity, Oliver waited for his agent to report back before acting. Inspector White (yes, that was his name) highlighted the miscegenation between African and Native peoples making plans to immigrate to Canada. The report is worth reading in detail:

The Indian has brought into the mixed race the cunning that the Indian is credited with, and has raised the lower and more harmless instincts of the negro, but only to a more brutal level, and with the combination he thus becomes a more undesirable person. He has worked alongside of the Indian until he has acquired a lot of that individual[‘s] shiftless methods and added to his own indifference of surroundings to his own carelessness in everything that elevates.[4]

White did pause to note that Creek Freedmen, “possessed … wealth much greater than most of the white settlers of the State.” Indeed, with their 160 acre allotments (see Part 1 for details), Freedmen had been doing well until Oklahoma statehood enshrined Jim Crow laws which disenfranchised them. Freedmen ran their own schools, newspapers (often in Cherokee, Creek, etc), and banks. The problem was not “shiftlessness” and “carelessness,” but rather a new regime of white nationalism enforced by lynching that made some Freedmen and African-Americans want to leave. In a 1997 memoir, Gwendolyn Hooks, a descendent of Black migrants raised in Keystone, Alberta, noted that Canadian government agents often referred to the settlers as “Indians.”

Inspector White’s report was the final straw for Oliver. He pushed Wilfrid Laurier’s government to issue Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324, which read, in part: “For a period of one year from and after the date hereof the landing in Canada shall be and the same is prohibited of any immigrants belonging to the Negro race, which race is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.”[5] The Order-in-Council never officially became law, but its publication demonstrated the hypocrisy of Oliver, who elsewhere claimed that Canada did not discriminate on the basis of race for entry.

The history of anti-Black racism in Edmonton is well documented. It is a painful and enduring part of the city’s history that has recently begun to be chronicled.[6] R. Bruce Shepard noted that Edmonton was at the centre of Canadian anti-Black racism in the 1910s. Even though the Klan’s influence waned in the U.S. South after the 1920s, the organization continued to grow in Edmonton, achieving peak influence in the 1930s. De facto—if not de jure—segregation occurred in swimming pools and movie theatres.

A descendant of the Black Pioneers, Deborah Dobbins, recalled that Black Edmontonians were relegated to the toughest and dirtiest jobs in meatpacking and janitorial work. So, between the rise of the Klan and the second-class treatment of Black people in Edmonton, most of the Black Oklahomans and their children stayed on the farm.

While Black pioneers had achieved self-sufficiency in places like Amber Valley, Campsie, and Keystone, rural life was extremely hard. Gwendolyn Hooks remembers children splitting wood, pulling root vegetables, and clearing land before and after school. A 50 mile trip to Leduc from Keystone would take four days by horseback.

The turning point seems to have been World War II. With many men leaving to for the fight in Europe, railroad jobs opened up to Blacks. The promise of an $80 a month wage lured many men off the farm and into Calgary and Edmonton. New arrivals to Edmonton found homes around Shiloh Baptist Church, which organized football and baseball teams, among other cultural activities. The first location was on 101 Avenue between 94 and 95 Streets, and Shiloh still holds services, albeit in a different location.

Big demographic changes led to the rapid urbanization of Alberta’s Black population by the 1950s. By this time, Black-owned businesses popped up around Shiloh Baptist Church, and Black superstars Rollie Miles and Johnny Bright powered the Edmonton Football Team to CFL dominance. By this time, the presence of African-Americans and their descendants had infused this northern city with gospel, soul food, and a championship sports team. A newfound visibility for Edmonton’s Black population was on display at the legendary Harlem Chicken Inn, owned by Hatti Melton. Melton’s remarkable—and somewhat mysterious—life deserves its own chapter in this story, which we’ll learn about in the third and last installment of the series.

Dr. Russell Cobb © 2021

Read The Last Black West: Oklahoma Freedmen Seek Refuge in Alberta, Part 1

[1] Judith Michener, “Willis, Uncle Wallace and Aunt Minerva,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=WI018.

[2] R. Bruce Shepard, Deemed Unsuitable (Toronto: Umbrella Press, 1997), 104

[3] Eli Yarhi, “Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324 — the Proposed Ban on Black Immigration to Canada”. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published September 30, 2016; Last Edited February 26, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/order-in-council-pc-1911-1324-the-proposed-ban-on-black-immigration-to-canada

[4] Quoted in Harold Martin Troper, “The Creek-Negroes of Oklahoma and Canadian Immigration, 1909–11,” The Canadian Historical Review 53, no. 3 (1972), 277.

[5] Yarhri.

[6] See the work of Bashir Mohamed and Chris Chang-Yen Phillips.