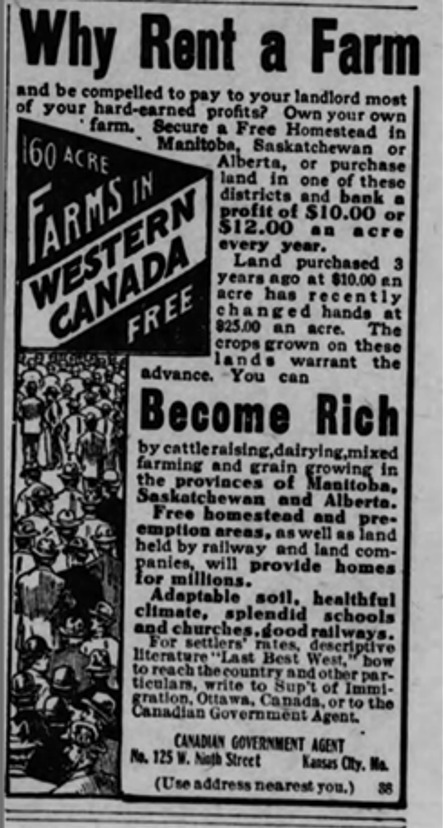

Advertisements promoting the “Last Best West”—a frontier open to all pioneers—have become an ingrained part of the Canadian national mythology. Like many myths, the imagery has a narrative power that does not always correspond with historical reality. We know that Canadian immigration policy explicitly favoured white British settlers and the government wanted to ban Black settlers. So, what explains this curious ad below?

The ad appeared in a newspaper in Boley, Oklahoma, on February 11, 1911. The Boley Progress ran glowing stories for years about fortunes made by wheat and dairy farmers on the Canadian prairies. Such ads appeared in American newspapers of the time, but the Boley Progress was different: it served an all-Black readership in a town Booker T. Washington called “the most enterprising Negro town… in the United States.”[1]

The first ads promoting Canadian immigration started running in the Boley Progress in 1908 and continued for almost four years. Its readers, then, would have been particularly receptive to the idea that Alberta and Saskatchewan held “adaptable soil, healthful climate, and splendid schools” over the years.[2]

The Boley Progress was not an aberration. Oklahoma had dozens of Black-owned newspapers that served readerships in all-Black towns, as well as the cities of Tulsa and Oklahoma City. The Tulsa Star, published out of “Black Wall Street,” ran a piece about the excellent crop yields in Alberta. “Anyone taking up land, will find Alberta an ideal province,” a source said. As scholars have noted, the “journalism” of these articles and the images conveyed by the “Last Best West” campaign were all part of a concerted effort to bring in white immigrants and push Indigenous people onto reserves.[3]

In an ironic twist, many of the Black people who managed to settle on the Prairies were not only of African descent, but citizens of Indigenous Nations themselves.[4] In the Black towns of Oklahoma, part of the attraction of western Canada was that it was, in fact, populated mostly by Indigenous people. “The lure to Canada was the fact that people who lived in this region were Indians and not whites,” wrote Jimmy Robert Melton in a thesis about the settlement of Amber Valley.[5]Melton estimated that around one-third of the Black immigrants were either citizens of the Creek or Seminole Nations or were related to those nations through kinship ties.[6]

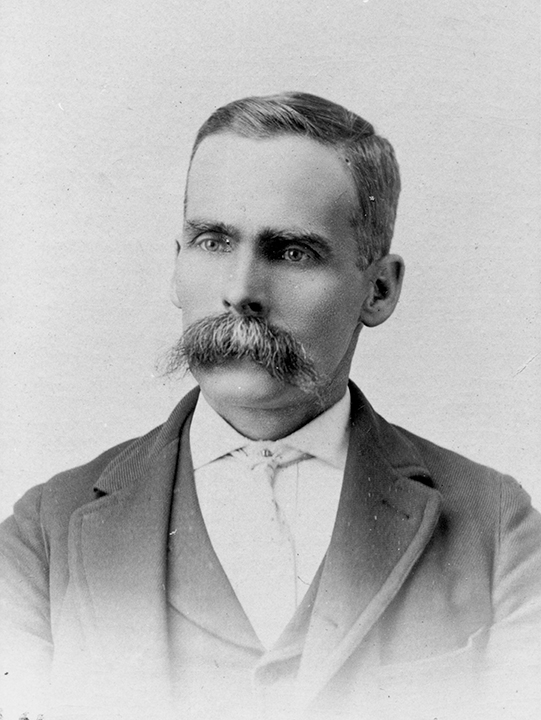

So, to sum it up: the Canadian government sold the idea of settlement to mixed Black and Indigenous people in Oklahoma while also acting to dispossess Indigenous people from their homelands. It was a bizarre scenario that owed much to the actions and ideologies of one man: Frank Oliver. Did Oliver know what he was doing?

Before we get to Frank Oliver and the arrival of Black pioneers to Edmonton, we need to travel back to Oklahoma at the end of the 19th century. At that time, the state was known as Indian Territory, and the Five Tribes retained their sovereign nations in the eastern half of the state. These nations–the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole–were labeled as the “Five Civilized Tribes” by the US federal government. The “civilized” label was applied because those tribes had become agricultural people, adopting many white settler practices. The most controversial of these practices was chattel slavery, and by the time the Five Tribes were evicted from lands in the American South, as many as one in three people living in those nations was of African descent.

Unlike their brethren in the United States, enslaved Africans in Indian Territory intermixed with members of the tribes, forming kinship networks, in which some Black people integrated into Indigenous clans and held important positions in the Five Tribes.[7] While some wealthy tribal citizens bought enslaved Africans from white traders, other enslaved Africans ran away to tribal nations. The Seminole Nation in particular proved to be a refuge for escaping enslaved peoples in Florida. The very word “Seminole” is thought to be a corruption of the Spanish word cimarrón, which designated a “runaway slave.”

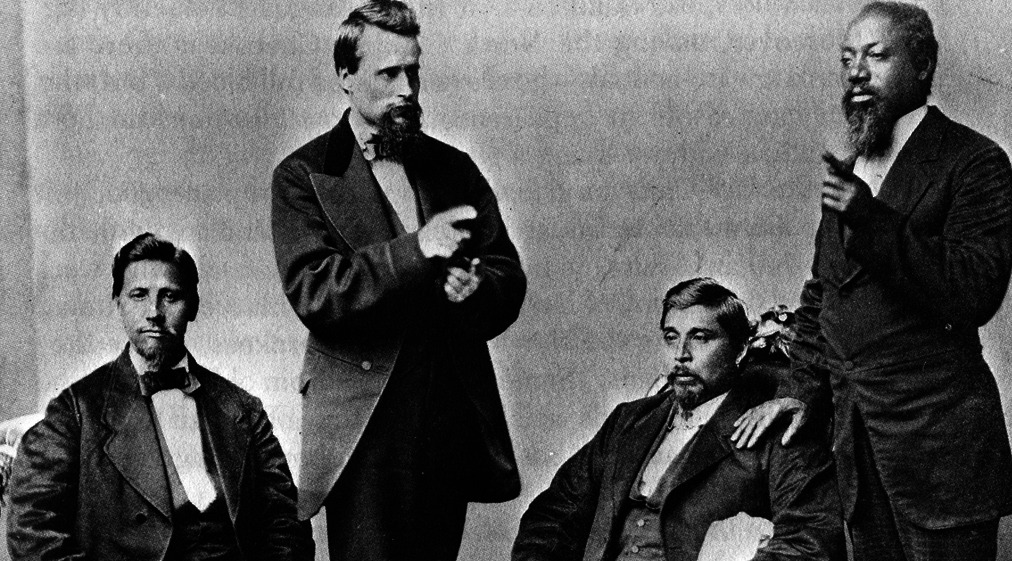

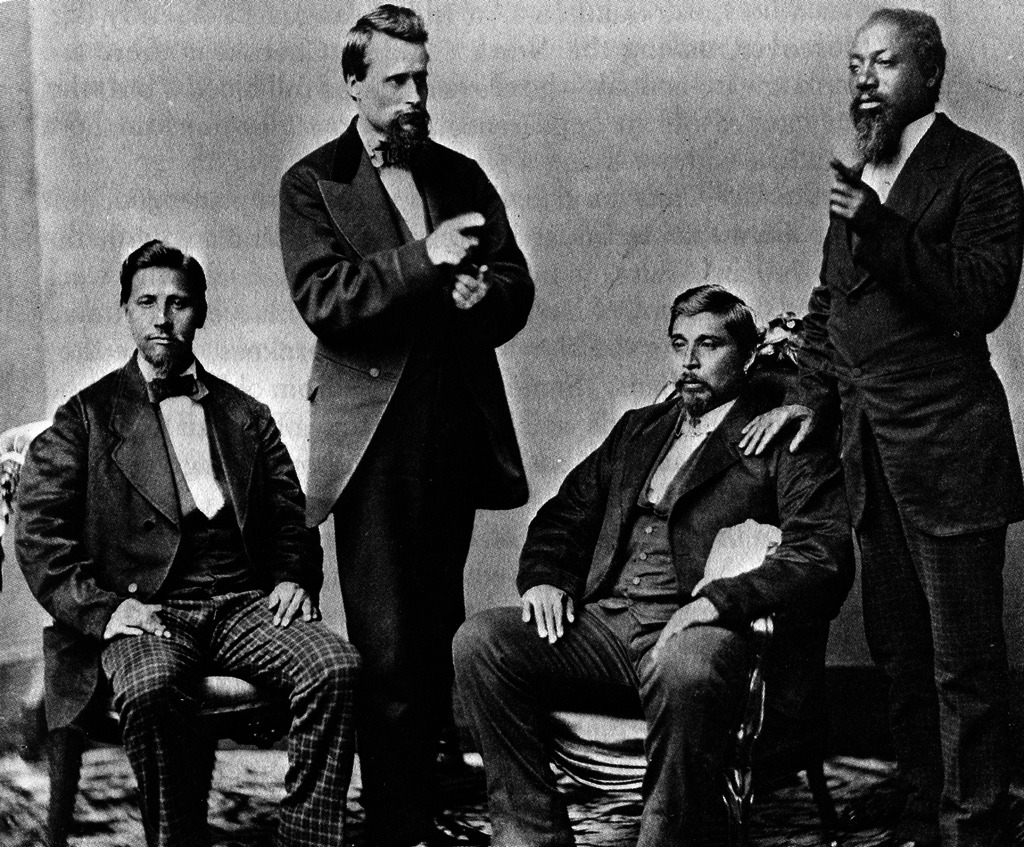

After the Civil War, many mixed-race citizens of the Five Tribes became prominent in government. They were judges, chiefs, and farmers. Black people served important roles as interpreters and translators, as they often spoke a variety of languages, including Creek, Cherokee, English, French, and Spanish. A photo of the Supreme Court of the Creek Nation after the Civil War demonstrates the degree of racial mixture in this one nation, with one member, Judge Silas Jefferson, clearly of African descent.

The U.S. Federal Government wanted to punish the Five Tribes for siding with the Confederacy during the Civil War. In reality, there was a civil war within the Civil War in Indian Territory and the issue of slavery was as hotly contested in Indian Territory as it was in the United States.

By the late 19th century, the federal government liquidated the tribes’ land base, and, in exchange, granted a quarter-section of land to each tribal citizen. With the notable exception of the Chickasaw, the Five Tribes granted citizenship to their former enslaved people and their descendants. The result was a tragedy for Indigenous sovereignty, but it resulted in a unique situation during an era of Jim Crow racism. While formerly enslaved people in the States never received their “40 acres and a mule” as reparations for slavery, their counterparts in Indian Territory suddenly owned 160 acres of farmland, much of it holding deposits of oil.

As Freedmen gained possession of land, they cultivated prosperous farms and dotted the territory with thriving all-Black towns. Fifty all-Black towns emerged before statehood in 1907.[8] This is precisely when names that would later become famous in Edmonton’s Black community—Melton, Mayes, Bowen, and Lipscombe to name a few—started showing up in Indian Territory. These people saw Indian Territory as the Promised Land, but they faced stiff opposition in obtaining land. The initial conflict was between Freedmen and “State Blacks,” who had come from the South. Freedmen may have been visibly Black, but, culturally, they sang Indigenous hymns, cooked Indigenous food, spoke Indigenous languages, and had Indigenous names (Silas Jefferson was better known as Ho-tul-ko-micco, “micco” being a title similar to “elder.”) This brings us back to Boley. The all-Black town had two colleges, one affiliated with the Seminole and Creek Nations, and one affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

When Oklahoma statehood came, however, all people of African descent found themselves victimized by a government every bit as racist as those in the Deep South. The first act of the Oklahoma Senate was a bill that categorized everyone with a drop of African blood as “Negro,” and subjected both Freedmen and “State Blacks” to the same discrimination. Some light-skinned Blacks found life easier if they could pass as “Indian,” even though that category posed its own problems.[9]

After statehood, Oklahoma witnessed some of the worst acts of racial violence in American history, most infamously the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. Lynchings, riots, and land theft were the order of the day. The discovery of oil on Freedmen allotments made things very precarious. Sarah Rector, a Creek citizen and the “richest black girl in America,” had to be spirited out of Oklahoma by Booker T. Washington’s men facing the threat of abduction.

Frank Oliver, the Edmonton promoter serving as Minister of the Interior (1905-1911), was horrified that his plan to recruit white, midwestern farmers to the Prairies was now taken up by Blacks—some of mixed Indigenous descent—in Oklahoma. Oliver was faced with a problem that will be familiar to anyone versed in the particularities of Canadian racism: he wanted to suppress Black migration without expressing his racism in explicit terms. Oliver did not want to upset relations with the United States, and Canada had an image to protect—a wide-open country with a history as a refuge to Black people.

To return to our question: Did Oliver know what he was doing? The government agents in charge of the “Last Best West” campaign simply did not understand the unique nature of Oklahoma: until statehood, it had been a haven for tribal sovereignty and Black freedom. Statehood had made both these things impossible, but Oliver—along with, to be sure, most Canadians—had no idea prairie propaganda would be taken at face value by oppressed people.

Oliver hired an agent who conducted a five-day investigation of the situation in Oklahoma. Black people, the agent said, were sending query letters to the Government of Canada, hoping to take the country up on its offer of free land. Oliver then instructed immigration officials to contact postmasters in Oklahoma to inquire about the race of the letter writers. Oliver hired a Black pastor from Chicago to tour the all-Black Oklahoma towns and preach on the harsh conditions in Canada.[10] Even these efforts, though, were not enough to keep Black Oklahomans away. And their first real stop in Canada after crossing the border in Emerson, Manitoba, happened to be in Edmonton.

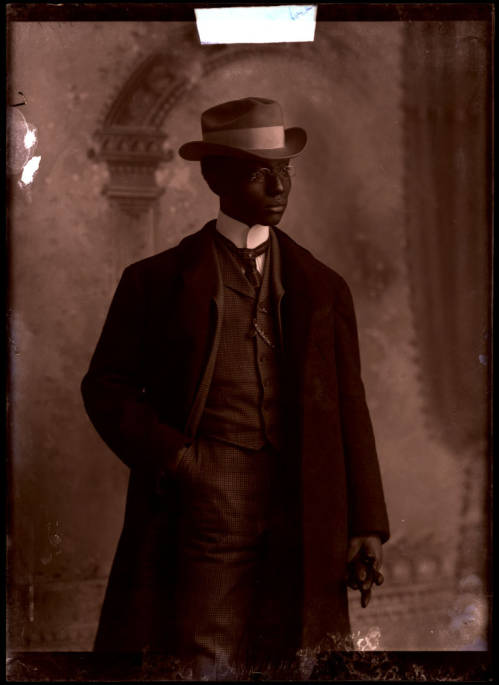

The first large group of Black pioneers arrived in Edmonton with nine carloads of a train equipped with horses and farm equipment. There, 194 people, led by Henry Sneed, waited in Edmonton for their homesteads to be ready.[11] Sneed’s first expedition to Canada had been a positive experience. He had been served at a saloon, seated next to a white man—something unthinkable in Oklahoma. Now, however, with a big group of Black migrants, Sneed found that Alberta was not the “ideal province” for all freedom-loving people that had been adverstised in the Boley Progress.

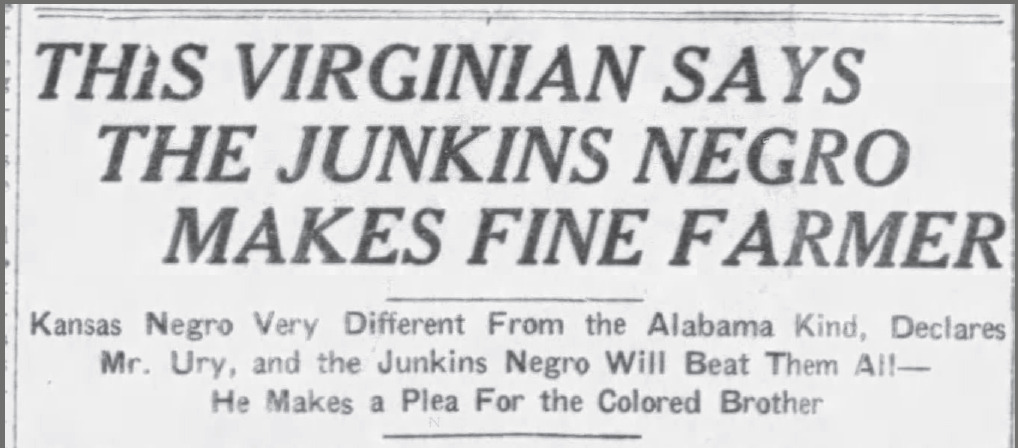

Reporters were ready to capture the moment of arrival in the new capital city. The Edmonton Bulletin—owned by Frank Oliver—ran a series of overtly racist caricatures of the refugees.[12] Even by the white media standards of the day, the descriptions and cartoons were vile. The Edmonton Journal adopted a more tolerant attitude. One edition of the evening paper featured a front-page story by a gentleman from Virginia who was appalled by the racism of Edmontonians. The man had come to Alberta to see the progress of the Black Pioneers.

The man, a certain Mr. Ury, had some choice words for Journal readers. “If some of those fellows who come prating around the streets of Edmonton, screaming to high heaven about the importation of negroes to the northwest would only stay home and do some work,” Ury said, “they might be proving themselves nearly as good as some of the negroes they think they can despise.”[13]

Ury went on to say that the Black settlement he saw in Junkins (later known as Wildwood), looked more prosperous, modern, and advanced than many of the White small towns around the province. As some Black families did, indeed, begin to thrive in their new Prairie environment, urban pressure against Black newcomers increased.

Frank Oliver had never meant to advertise Canadian land to African-Americans, but the newcomers were here to stay. While the gentleman from Virginia celebrated their resilience, Oliver sought to make life miserable for those already here, and to slam the door shut on those who might be tempted to follow.

Dr. Russell Cobb © 2021

Read The Last Black West: Oklahoma Freedmen Seek Refuge in Alberta, Part 2

[1] Larry O’Dell, “Boley,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=BO008.

[2] “Why Rent a Farm. Become Rich,” The Weekly Progress, February 2, 1911.

[3] See, for example, Daniel Francis, National Dreams: Myth, Memory, and Canadian History (Arsenal Pulp Press, 1997).

[4] See Harold Martin Troper, “The Creek-Negroes of Oklahoma and Canadian Immigration, 1909–11.” The Canadian Historical Review53, no. 3 (1972): 272-288. muse.jhu.edu/article/570441.

[5] See Jimmy Robert Melton, “Amber Valley: A black enclave in northern Alberta, Canada” (1994). Theses Digitization Project. 940. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/940, 31.

[6] The question of indigeneity among the Black Pioneers is hotly debated and should be researched further. For obvious reasons, many new arrivals to Canada may have chosen to hide their tribal affiliations. Melton, however, attests to warm relations among the Plains Cree and Black Pioneers.

[7] See Kevin Mulroy, The Seminole Freedmen: A History. (University of Oklahoma Press, 2007).

[8] Tulsa World, “The 13 historic all-Black towns that remain in Oklahoma,” updated November 20, 2020.

[9] A fascinating, although tangential, case in this regard is Buffalo Child Long Lance, a Black man who passed as Cherokee in North Carolina, and then ended up as a local celebrity in Calgary.

[10] See R. Bruce Shepard, Deemed Unsuitable, (Umbrella Press, 1997), 87

[11] R. Bruce Shepard, “Diplomatic Racism Canadian Government And Black Migration From Oklahoma, 1905-1912” (1983). Great Plains Quarterly. 1738. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1738

[12] Although the Black Pioneers are not typically described as “refugees,” the spate of lynchings and massacres that led to their departure from Oklahoma meet the definition established by UN Refugee Agency.

[13] “This Virginian Says Junkins Negro Makes Fine Farmer,” Edmonton Journal, May 11, 1911.