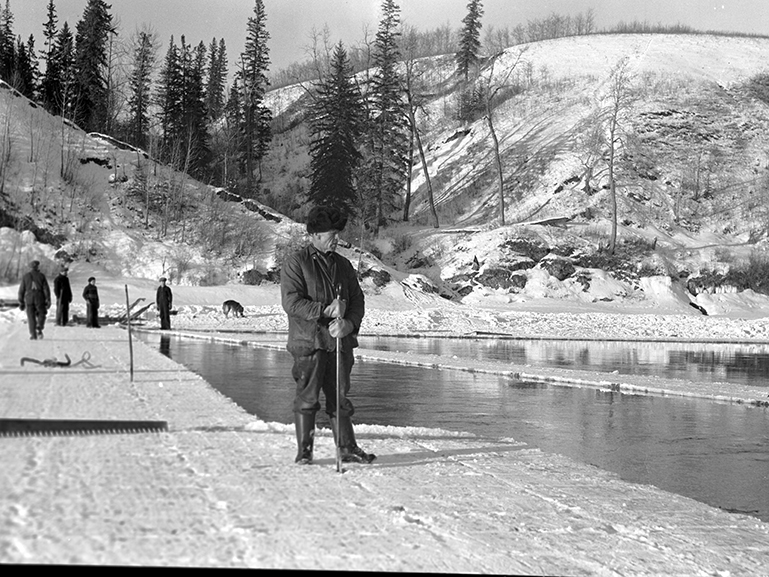

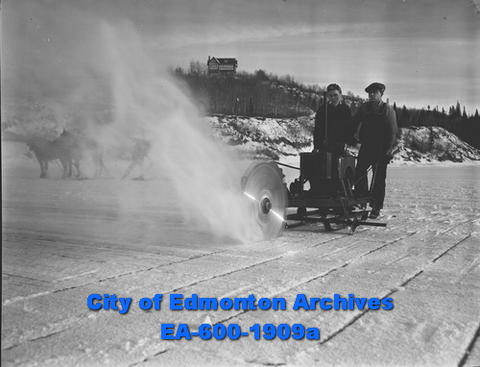

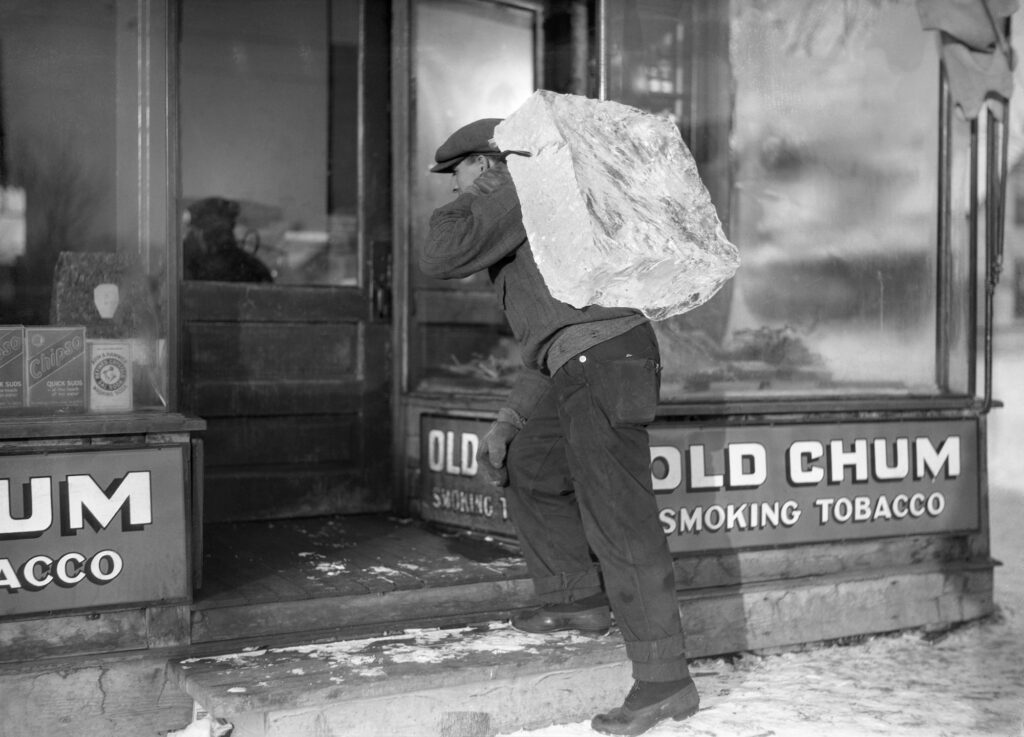

There is a fascinating series of photos in the Hubert Hollingworth Collection at the City of Edmonton Archives which shows men harvesting ice from the frozen North Saskatchewan River in 1938. Like the sequence in the Disney animated movie Frozen, crews worked to carefully cut the ice into 50- to 100-pound (22- to 45-kilogram) chunks and hoisted them onto horse-drawn wagons. The chunks were then hauled to nearby cold storage barns. The one at the Edmonton Ice Company had room to store 8,000 tons (7,257 kilograms) of ice – enough to last through the summer and until the next winter’s harvest.

Even with the arrival of somewhat unpredictable electricity and the burgeoning popularity of refrigeration in the 1920s, many citizens and businesses clung fiercely to their insulated cubicle iceboxes. “Ice is the Safe Form of Home Refrigeration,” declared an Arctic Ice Company advertisement in the June 30th, 1927 edition of the Edmonton Journal.1 “Ice is the simple, natural way to secure the proper low temperatures of your refrigerator. Ice costs less than any refrigerating method and never goes out of order.”

The “ice age” in Edmonton began at the turn of the century with the establishment of the Edmonton Ice Company and the City Ice Company, followed by the Arctic Ice Company and the Twin City Ice Company, in 1912. They were headquartered on the Ross Flats (today’s Rossdale) on 100 Street between 97 and 98 Avenues, with storehouses for ice and stables for horses and delivery wagons.

Ice was gathered from the North Saskatchewan at various locations, mostly upstream from the city, and from Wabamun Lake, 70 kilometres to the west. The harvest provided seasonal employment for 40 to 60 men.

A 1912 article extolling the virtues of the new Arctic Ice Company said: “The pure snow waters of winter flow into the lake over pebbly reaches from the highlands and produce a body of water unexcelled for clearness and purity.” 2 The ice taken from the North Saskatchewan was “as pure as nature can make it. Coming as it does from the snow-fed stream of the surrounding country, filtered through the immense gravel beds along the river, and fed from thousands of pure springs, the water is as limpid and as translucent as a diamond.”

In the 1920s, the electric refrigerator was beginning to catch on, yet Arctic Ice remained bullish about future prospects and constructed a new facility at their Rossdale property. A 1927 company ad in the Journal noted that the cost of a small mechanical refrigerator was equal to 20 years of ice delivery and that the “annual cost of electric current alone for the household mechanical refrigerator will pay the ice bill for three average families for two years.” Not only that but, “you can fill your ice chamber and be gone for a day or two and know that your food is fully protected…no fuses to blow, belts to break…”

A newspaper spread for Twin Ice Company in the June 30, 1927 edition of the Journal put it this way: “There is no substitute for ice. Our reputation is based on reliability. Every day, rain or shine, hot or cold, our ice man will call at your door, ready to provide you with pure ice and honest weight.” Edmonton ice was in demand near and far, and Arctic Ice shipped train car loads of ice “anywhere in the West.”

History shows that the electric refrigerator eventually won the home battle, but the “ice age” in Edmonton wasn’t done just yet. Whenever the power went out and food was subsequently spoiled, those who had held on to their iceboxes could proud say, “I told you so.”

James Gillett, who started working as an iceman for the Arctic Ice Company in 1909, remembered the teams used to be able to haul three tons of ice per trip. “People used a lot of ice in those days,” he was quoted as saying in an August 16, 1967 Edmonton Journal article. “I remember one route I worked on had 62 customers in two blocks. The kids used to follow along for shavings of ice to suck and sometimes if I took too long on a call, the kids would get in the back of the wagon and chip their own ice slivers.”

“It was a good trade,” Gillett said. “We made about as much as any other labourer in the city. I think I earned about $2.85 a day when I started in 1909.” Eight of Gillett’s sons (he had 11 children!) worked at some point for the ice company.

Harold Blacklock, who began working for the Arctic Ice Company in 1943, recalls ice harvesting began on the river once it was thick enough for safety, usually 20 inches (50 centimetres) or so, and usually in January. “Before freeze-up, a spot was chosen where there was [sic] no rapids and the water was deep enough to run smooth. A special plow, which cut about four inches deep, was used to cut the ice in strips two feet wide. This plow was pulled by a team of horses,” he stated.

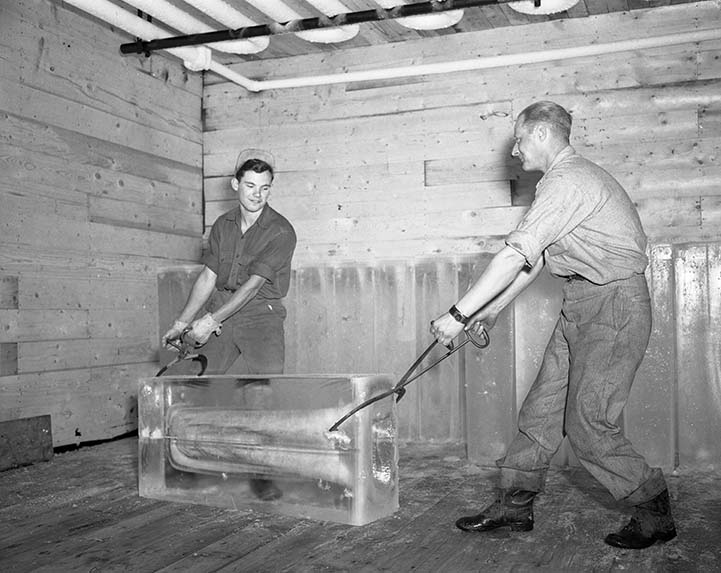

The ice was cut into blocks two feet by four feet (60 to 120 centimetres) while still in the water and then lifted out with a grappling hook attached to a chain. A team of horses would then pull the block out of the water and it would be loaded on a sleigh to begin its journey to the icehouse and then to a waiting ice box.

The days of horse-drawn ice wagons came to an end in 1949, when the company bought a fleet of trucks. Ice was harvested off the river every winter until 1950, when Arctic Ice opened its new $150,000 manufacturing plant at 10091-97 Avenue.

The plant, designed by Edmonton architects Martland and Aberdeen, replaced the smaller structure on the site and boasted a production capacity of 72 tons a day. That was enough ice to meet the city’s requirements and maintain an enormous reserve of 1,500 tons (1.36 million kilograms) against the possibility of machinery breakdowns or power failures.

Reporting on the July 1950 opening of the facility, the Edmonton Journal noted it was the most modern of its kind in Canada and explained the advantages of refrigeration cooling systems and plant ice. “Although manufactured ice is naturally purer than river or lake ice, probably its greatest advantage is that it can be cut to an exact size. The user is sure of always obtaining the same size block and is spared the familiar bother of trying to cram an oversized chunk of ice into a small refrigerator.”

Even with the switch to manufactured ice, the company did not totally leave the past behind. It harvested ice at Wabamun Lake well into the 1960s, cutting 600-pound (272-kilogram) blocks from the lake for sale to the Canadian National Railway, which stored them in ice houses at Calder and Jasper.

The ice (22,000 tons of it in the winter of 1963/64) was used in non-mechanical refrigerator cars to protect perishable freight such as fruit, vegetables and frozen food. That winter, the crew cut 15 acres (six hectares) of ice, marking the lake surface into blocks 22 inches wide and 44 inches long. Floats of 80 to 100 partly cut blocks were pried off the main ice by specially designed steel bars. The ice pushed to the edge of the lake, was loaded by conveyor chain onto flat deck trucks and then brought to the railway line.

Harold Blacklock worked for a time during the Second World War as a tong man at the Calder icehouse until the freezing cold from the ice gave him arthritis in his hands and he decided to find other work. “I would catch a block of ice as it came down the rails and lead it to its final resting place. I had a helper who would push it. Two others worked as we did, taking alternate blocks. One man worked steady with an ice chisel smoothing the level of the ice and filling between the blocks with ice chips.” 3

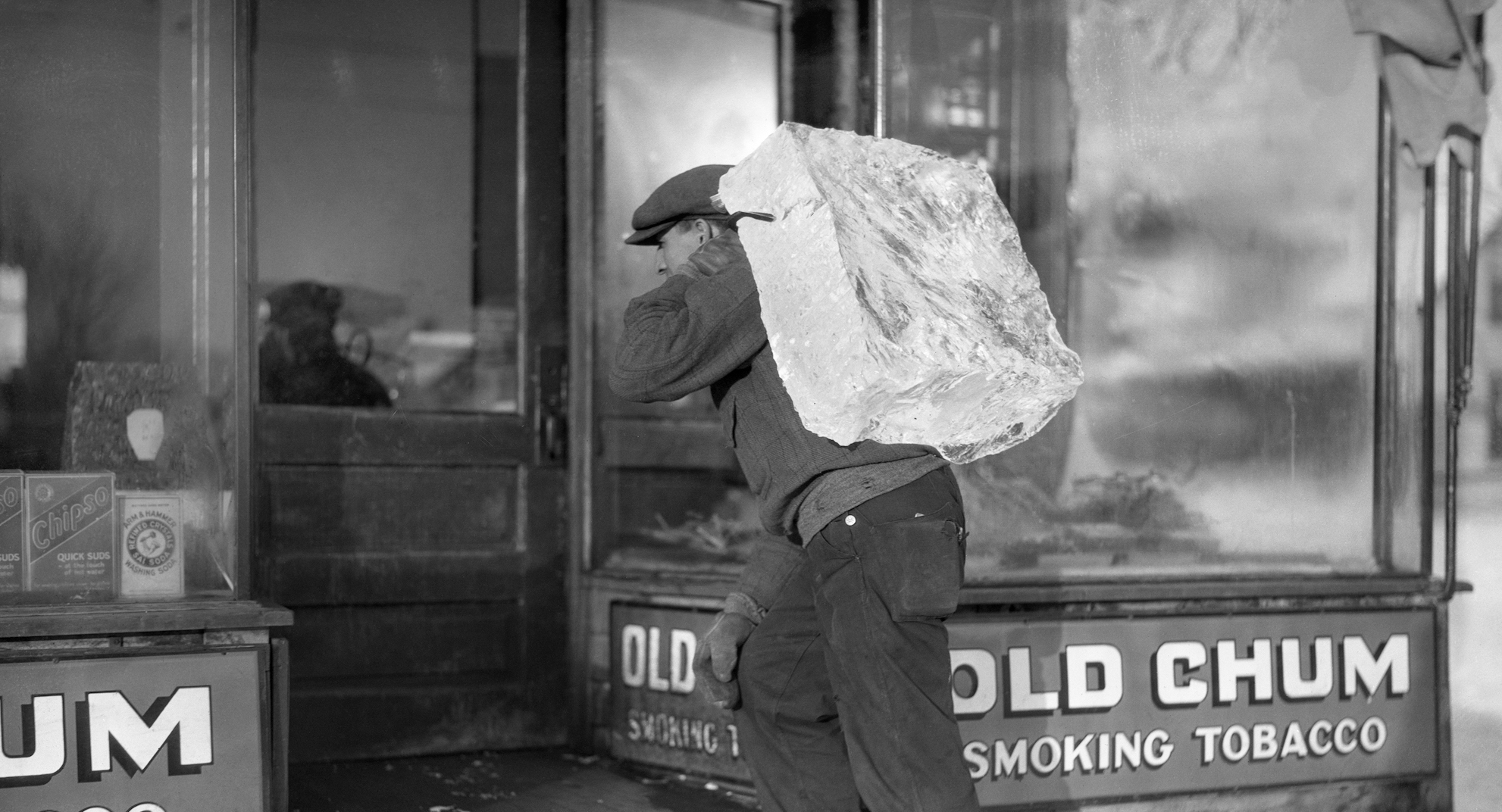

The 1950 Arctic Ice plant survived until 1978, when the City of Edmonton deemed it a fire hazard and too expensive to heat. Arthur Jellis, who appraised the property and buildings for the city, remembered watching ice harvesting as a boy and was quoted in a March 2, 1978 article in the Edmonton Journal. “It was a pretty big deal when I was a kid. The men would wear rubber aprons to keep their backs dry. They’d carry the big blocks on their backs.”

Years later, even after the refrigerator had become a fixture in nearly every household, there were those who still believed the old way was better. “I guess we won’t see ice wagons anymore,” Gillett said in the 1967 Journal story. “But I still say the food tastes better from a real ice box.”

Lawrence Herzog © 2021

[1] Clippings files, City of Edmonton Archives.

[2] https://www.edmonton.ca/city_government/documents/PDF/ArcticIceCompanyLimited.pdf.

[3] Harold Blacklock. Written submission held at City of Edmonton Archives.