Sophie’s Way is a twist of concrete winding up a short but steep hill in the Edmonton river valley. The path is marked by a street sign on the Victoria Park Golf Course and Driving Range. This past winter while cross-country skiing, I stumbled, well, slid onto Sophie’s Way. The trail name sparked my curiosity to find Sophie and eventually led to a deeper understanding of Edmonton and its history of names.

If it hadn’t been for COVID-19, I wouldn’t have been on the Victoria Park golf course. Before the pandemic shut down everything, I regularly went to a fitness studio on Jasper Avenue. Now I had to find other ways of keeping in shape. The river valley trails offered exercise at the regulated two-metre distance and provided fresh air while quarantining in a downtown condo. So off I went with my skis. It was while gliding past a northeast section of the golf course that I noticed a path leading up to a tee-off. Next to it was a city street sign with the words Sophie’s Way written on it.

“Who is Sophie?” I wondered while catching my breath. “Why does she have a path named after her?”

At home, I looked up the name on the internet and couldn’t find anything. I searched and searched and found nothing connecting Sophie to the golf course. However, I did come across a history of the area and the different names it has had.

Left: A street sign marking Sophie’s Way. Photo courtesy of the author, May 2020. Right: A Google Map image of the Victoria golf course. Sophie’s Way is marked by the pink dot. Image captured by the ECAMP Team, November 2020.

We use names to honour people and history. We name streets, buildings and parks after those we want to remember. Names anchor us to our communities, our land. Without names, identities and cultures can be displaced and sometimes, disappear. Names also tell stories. The land the Victoria Park Golf Course and Driving Range calls home was first used by several Indigenous nations, such as the Nehiyawak (Cree), Nahkawininiwak (Saulteaux), Nakota Sioux and Niitsitap (Blackfoot) as a gathering place and burial grounds. Each nation had a name for the land.

The Nakota Sioux traditionally call the area ti oda, Many Houses, and the Niitsitapi call it omahkoyis, Big Lodge. The Nehiyawak traditionally call Edmonton amiskwaciy-wâskahikan, translating to Beaver Hills House. Mackenzie Brown, an Indigenous advocate, writer and artist, said the Nêhiyawêwin language isn’t like English. Nêhiyawêwin is verb- and action-based and the action of naming tells the story of the land.

“When that name is changed, you miss the real meaning. Amiskwaciy-wâskahikan, Beaver Hills House, was a place where people would come and forage. There was a diverse amount of plants and animals here. When the name was changed to Edmonton, it meant a place from England. It doesn’t tell the true story of the land,” Brown said.

Brown said colonialism had a massive impact on the way Indigenous people related to the land because it taught them that there were boundaries. The use of names meant drawing imaginary borders and lines while dispossessing the original inhabitants of their land and resources.

“We believe in the idea that land is to be shared. Not owned,” said Brown. “We all need to care for Mother Earth but colonialism turned the land into a resource, not a living being.”

In the late 18th century, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) claimed land near what’s now the city of Fort Saskatchewan and founded the Fort Edmonton trading post. Kathryn Ivany, a City of Edmonton archivist, said there are two versions about how Fort Edmonton got its name — and no one knows which one is true. Both stories have an English HBC employee naming the fort after Edmonton, U.K.

“Places were often named by the landowner,” said Ivany. “Settlers tried to eradicate the Indigenous names.”

Many of the traditional Indigenous names in Edmonton were changed to reflect settler cultures.

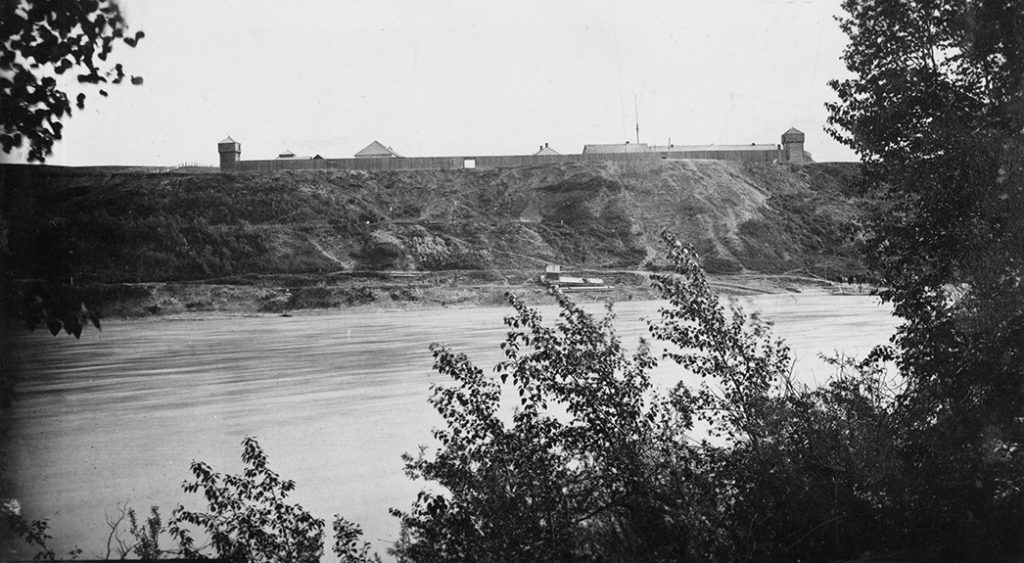

In the early nineteenth century, HBC moved its trading post into the Rossdale area. The land was named after Scottish businessman Donald Ross, who had a homestead on the flats. Around 1830, Fort Edmonton moved to a rise just above the North Saskatchewan River because of flooding. Ivany told me that HBC’s Rossdale lands were then used at various times for a nine-hole golf course, a racetrack, a cemetery, and a shooting range. I learned a lot about the area’s rich history from the archivist but she wasn’t able to find anything about Sophie’s Way. Ivany suggested I talk to Cory Sousa, the principal planner for the city’s naming committee.

Edmonton’s naming committee is the gatekeeper of official civic names from streets to municipal facilities. Formed in 1956, it is one of the oldest of its kind in North America. Anyone can forward a name to the committee and it will decide, through a five-step process, if the name fits the criteria for a civic landmark. So how did Sophie’s Way fit the criteria? Sousa has been in his job since 2008 and has never heard of the pathway. He said the name doesn’t come up in the database.

“It’s bizarre,” he said. “It’s not on record or on any of the maps.”

I took the mystery to social media. One person responded with the possibility that Sophie was the daughter-in-law of former mayor and businessman John A. McDougall. Sophie and her husband, John C. McDougall, had lived in Hilltop House — a two-and-a-half-storey brick mansion built in 1913 on top of a steep downtown escarpment. I contacted the Edmonton and District Historical Society (EDHS) about the theory but alas, another dead end.

Information is surfacing about John A. McDougall and his business partner Richard Henry Secord. They started the McDougall & Secord Company at the tail end of the 1880s as competition for HBC’s fur trade. The pair also exploited Indigenous peoples through land dealings. Despite this, their names are found throughout Edmonton with two neighbourhoods bearing the names Secord and Central McDougall.

McDougall and Secord weren’t the only ones with a history of oppression. Oliver’s namesake, Frank Oliver, was an early settler and Member of Parliament who not only maltreated Indigenous peoples but minorities, too. The Oliver Community League is calling on the city to rename the inner-city neighbourhood.

In the case of Oliver, McDougall and Secord, the historical wrongs go beyond erasing the history of the area’s first inhabitants by commemorating figures who oppressed Indigenous people. Meanwhile, in a sign of change, the company responsible for the name Edmonton is leaving the city’s core. HBC is closing its store in the City Centre Mall. The Bay/Enterprise LRT station is the last vestige of HBC downtown, a few metres away from Amiskwaskahegan (Beaver Hills House Park).

When names are changed, cultures can be untied from the land. But it can also be reclaimed. Mackenzie Brown said that many elders have held on to the traditional knowledge of names despite being forced into residential schools.

“It’s a testament to the fact that the Indigenous people don’t want to be assimilated after a hundred years of colonialism.”

The naming committee principal planner, Cory Sousa, said Indigenous naming is a top priority and the city is fine-tuning the process.

“We’re on Treaty 6 land. The people have been here for thousands of years and we haven’t recognized their history.”

A few communities already bear Indigenous names. Garneau, near the University of Alberta’s north campus and just off the popular Whyte Avenue area, is named after Laurent and Eleanor Garneau. The couple, whose heritage was Métis, participated in the Red River Resistance/Rebellion of 1869-70 before coming westward to Edmonton. As well, Mill Woods, Blue Quill and Bearspaw are all communities, which have incorporated Indigenous names in their public parks and schools. Tipaskin School is named after the Nehiyawak word for “reserve” and references Papaschase Indian Reserve 136. The reserve was on approximately 65 square kilometres of land, which now includes Mill Woods and other northwestern neighbourhoods. More recently, Edmonton has named the new LRT bridge that crosses the North Saskatchewan River the Tawatinâ Bridge, which is Nehiyawak for valley.

“By no means does it mean we’re limiting or ignoring other cultures,” said Sousa. “There are many Lebanese names, Iranian and Sikh names in Edmonton, too.”

Sousa points to Gurdwara Road, an honourary name for a street in Mill Woods. Sohan Singh Bhullar Park is in the same area. Sohan Singh Bhullar came to Edmonton in 1953 and helped newcomers feel at home. The park honours his work.

What was Sophie honoured for? A long-time Edmonton-area woman, Lavonne Hailes, theorized that the path’s name stemmed from the practice of giving names to golf course holes in the late 1980s. She thought Sophie was a reference to Sophie Morigeau, a late 19th-century Métis businesswoman. Lavonne emailed numerous contacts, asking if they knew anything about Sophie’s Way.

Finally, someone did. Sydney Gross, assistant to Ward 6 Councillor Scott McKeen, talked with a supervisor at the Victoria Golf Course. He told a story about a woman who was an advocate for citizens with mobility issues. Her name was Sophie and she belonged to a golf league that played on the course. She had trouble climbing the staircase that leads to the 13th green. A paved cart path was put in and a street sign, “Sophie’s Way,” was erected. I’m still waiting for this information to be corroborated but it seems like a plausible story.

This isn’t the ending I was looking for when I started following Sophie’s Way. I had hoped to introduce you to someone. However, Sophie’s Way is more than one person’s story, it’s many — it’s the story of the Indigenous people who first lived on this land, the story of settlers who renamed it and the story of the people who live here today.

Lea Storry © 2020

Sources

Brown, Mackenzie. “Amiskwaciy Waskahikan: Indigenous Experiences in Edmonton,” Explore Edmonton. Retrieved Aug. 1, 2020.

CBC News. “Plains Cree language used to name Edmonton LRT bridges” CBC Edmonton Retrieved June 25, 2020.

City of Edmonton. “Indigenous Place Names of Edmonton” City of Edmonton’s Open Data Portal. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

City of Edmonton. “Naming Process Committee.” Retrieved June 25, 2020.

City of Edmonton. “Victoria Golf Course and Driving Range.” Retrieved April 14, 2020.

Ivany, Kathryn. “River Crossing Stories, Donald Ross of Rossdale,” City of Edmonton. Retrieved Sept. 9, 2020.

Paches, Robyn. “Names—A Unifying Tool, OCL President Column” The Yards, Fall 2020, page 4.

Priestley, Mel. “Where did Edmonton get its name? The origin of Edmonton’s name isn’t glamorous, but it dates back almost a millennium,” Taproot Edmonton Retrieved June, 12, 2020.

Ryning, David. “King of the Hill, Hilltop House: A Gracious Echo of City’s Past,” Edmonton Community Foundation. Retrieved May 29, 2020.