- mikâwê (mother)[1]

When Dr. Anne Anderson was born on a river lot farm east of St. Albert in 1906, she was so tiny and frail that her mother worried for her survival.

“I was so small my mom made my bed in a shoebox lined with rabbit fur,” said Anderson at her 84th birthday party. “She thought I was going to die. She asked a medicine man to make me strong.”[2]

The medicine man reassured Elizabeth Callihoo that her daughter would not only grow to be a strong, determined woman, but that she would accomplish great things in her life.[3]

It didn’t take long for Anderson to start proving this prophecy right. The eldest daughter in a family of ten children, she grew up fast and began working to support her family at sixteen when her father died of acute appendicitis.[4] This ended her school career, which had included some years of study at Bellerose School in St. Albert and the nearby Grey Nuns Convent. Because she was taught in English only, her mother insisted that Anderson and her siblings speak their own language at home.

“She spoke to us and we had to answer in Cree,” recalled Anderson. “She said ‘the white lady at the school can teach you English but this Indian home must always have the Cree language’.”[5]

2. pâhku’chimew (promise)

When Anderson’s mother was dying, she promised her that she would pass on the Cree language by teaching it and writing it down.[6] For centuries, Canada’s colonial policies sought to eradicate Indigenous languages, tearing children away from their parents and sending them to residential schools, where they were punished for speaking their mother tongues.[7]

“Not allowing the aboriginal Cree-speaking people to use their own language in their own environment has produced a very confused generation,” wrote Anderson in the preface to one of her books. “One must live in his own cultural environment to remain happy. Today Cree is not spoken by many of the younger generation, but more and more are becoming interested in learning and preserving the language.”[8]

It was largely due to Anderson’s efforts that this spark of interest was rekindled, carefully tended, and has grown into a powerful fiery passion for the language.

Photos provided by the ECAMP Team, August 2020.

3. kiskino humâkewiskwew (teacher)

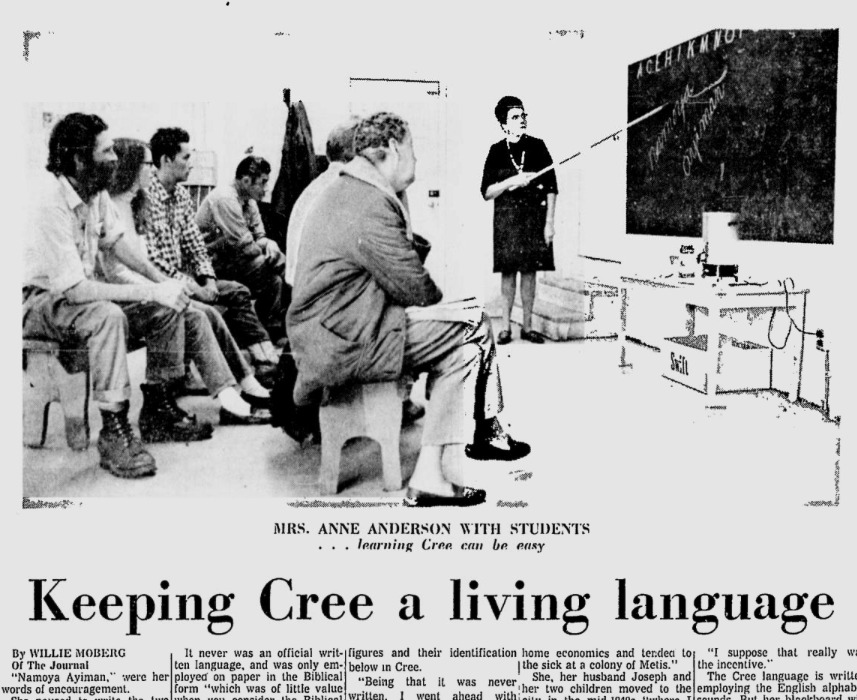

Anderson’s first foray into teaching came when she placed an ad in the newspaper offering to tutor people in Cree. She expected to receive only 10 responses, if that, and was blown away when 50 people expressed interest.[9] She began teaching private lessons, and then started teaching classes in Edmonton’s public schools. This helped her expand her instruction greatly, but it came with its own set of challenges. Although her students were enthusiastic, many of the public school administrators were indifferent,[10] if not outright hostile,[11] to her activities.

“I was teaching in the public schools, but they would only allow a half an hour a day,” said Anderson. “The little Native kids wanted to stay longer in the classroom but they (the schools) wouldn’t allow them to. I used to say, some day I’m going to have my own school.”[12]

4. kiskino’humâto kamik (school)

After 16 years of teaching in the public school system, Anderson was able to open the Dr. Anne Anderson Native Heritage and Cultural Centre in 1984. The centre quickly became a vital community hub, providing not only Cree classes for children and adults, but also serving as a library, a repository of cultural artefacts, and a storefront for Indigenous and Métis arts and crafts.[13]

Anderson provided most of the funding for the centre from her own money, and she had to make frequent pleas for financial support to the provincial government (and when that failed, to the wider community).[14] At one particularly dire moment in the centre’s history, a collection of Edmonton Métis and Indigenous groups organized a hastily assembled benefit dance, which raised over $1,000 to keep the centre alive.[15]

Despite these financial challenges, surging demand, and shoestring budgets, Anderson and the teachers she employed continued to teach hundreds of people—not only at the centre, but also university students at the U of A and Grant MacEwan, patients at the Charles Camsell Hospital, inmates at the Fort Saskatchewan Correctional Centre, women at the YWCA,[16] and young people in group homes.[17]

5. musinahikew’êniw (writer)

Concurrently with her teaching, Anderson (or Doctor Anne, as she had become known in the community)[18]had started to fulfill the second half of her promise to her mother, and preserve the Cree language in writing as well as by teaching it. Her first book, Let’s Learn Cree, was written with the help of her niece Elaine at the kitchen table of her Jasper Avenue apartment. It was published in 1970.[19] Although it was a simple textbook, it was nonetheless ground-breaking; “at the time, the only books in Cree were religious stories written by missionaries.”[20]

Shortly thereafter, Doctor Anne founded Cree Productions, a company dedicated to producing educational resources that could spread the Cree language beyond the reach of her own classes.[21] Under its umbrella, she began to write more books. She proved to be phenomenally prolific, filling the long-unsated desire for Cree content by cranking out dozens of titles—not just on the Cree language, but also books about Métis history, herbal remedies, Indigenous legends, children’s colouring books,[22] and even cookbooks.[23]

6. meskewe’yihto usina’hikun (dictionary)

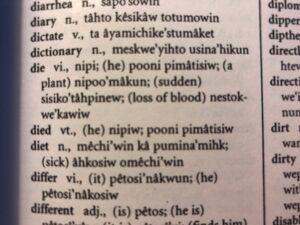

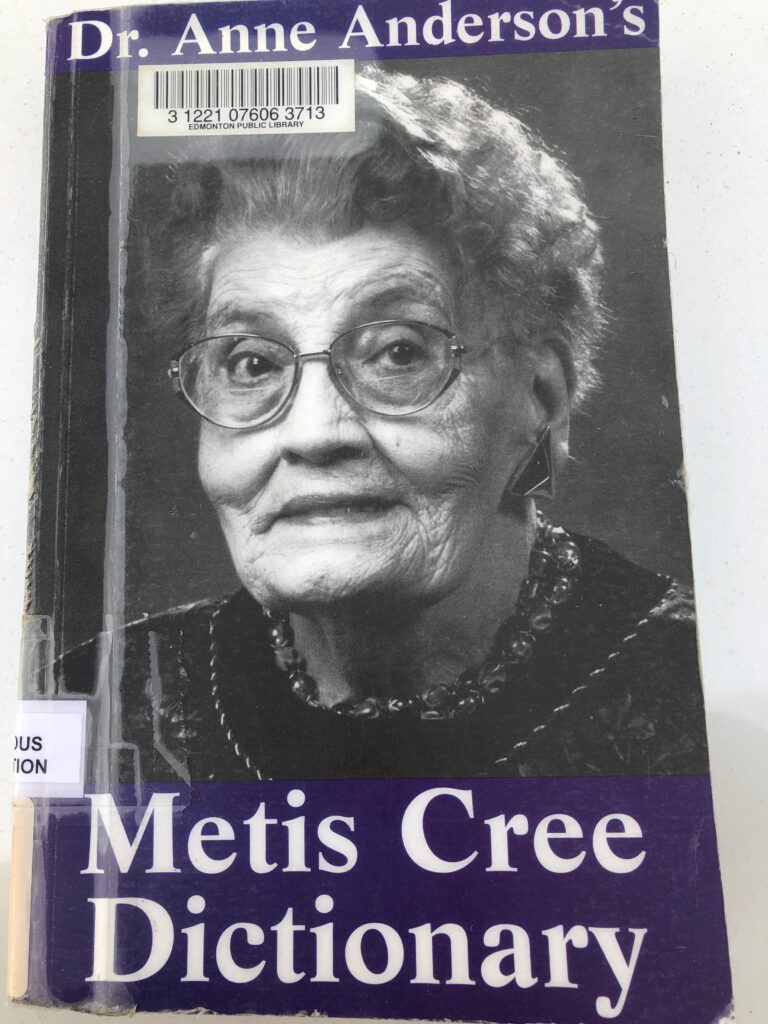

All told, Doctor Anne wrote nearly 100 publications.[24] The jewel in her literary crown was her dictionary. In 1975, she translated a 38,000-word English dictionary into Cree,[25] creating Dr. Anne Anderson’s Metis Cree Dictionary, one of the most comprehensive catalogues of the language ever assembled. She continued to update this dictionary over the years, noting that new words were constantly having to be created for new inventions like microwaves and computers.[26] As the years progressed, her research extended beyond translating Cree in the Roman alphabet, and into studying Cree syllabics.[27]

7. mâmitone’yichikun (memory)

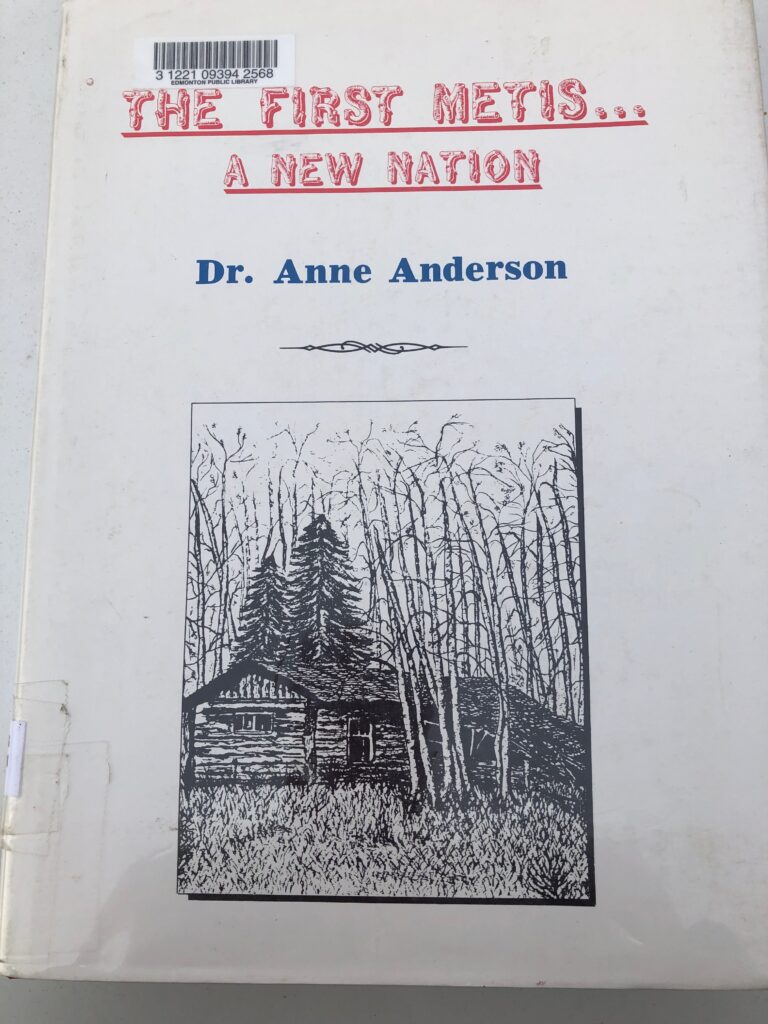

A decade after having written her dictionary, Doctor Anne produced another landmark title in her ever-growing bibliography. The First Métis – A New Nation provided a historical overview of many Métis families in Alberta, documenting stories that might otherwise have been lost. The book offers a glimpse into the way of life of Métis and Indigenous people in the Edmonton area, and how rapidly and profoundly it changed over the generations.

“For hundreds of years the wisdom of the nomadic people was ignored,” wrote Doctor Anne in the introduction to this vital record. “However, today, they are teaching us their wonderful, and sometimes strange, ways. It is too vital a matter to ignore them any longer… It is my hope that this book will better acquaint the world as well as those who read it with the history, nature, and character of these people. There is truly a wealth of history behind these particular nomads. The blood of their veins runs through the veins of my body with complete understanding in our togetherness.”[28]

8. notikwew (elder)

One of the most remarkable things about Dr. Anne Anderson is that she only started her illustrious career in her mid-sixties. Despite her promise to her mother, as it so often does, life got in the way. Doctor Anne got married and had children. She moved to Spruce Grove, and then to Oregon, and then back to Alberta to live in Edmonton. She worked as a supervisor at a Métis settlement (and learned to type, which would prove very helpful later on) and then worked in nursing. She didn’t teach Cree to her own children, following her first husband’s desire to hopefully spare them from the discrimination that their generation had faced and “let them grow up as white people.”[29]

But her promise to her mother was always there, and one day she finally had the time to commit to it.

“In 1966 I had nothing to do, but, I [recalled] what my mother said to me just before she died. She said: ‘Don’t you ever forget that your mother is Indian, and she is very proud of it.’”[30]

So, Doctor Anne placed her auspicious newspaper ad. And the rest, as they say, is kayâs âchimo’win.

Photo courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives, EA-742-1.

9. pêkisk we’wina (words)

There are so many words to describe Dr. Anne Anderson. kiskinoh’tahi wew (leader). notinikew êyiniw (fighter). âwiyak kâ kiskeyihta tânisi pêkis’wewina tesi tusina he (linguist).

She was once described as the mite (heart) of the Métis Nation.[31] She was a pillar of her mâmâwi e âyâhk (community) and a relentless advocate for her nistum pimachi’howin (culture).

She amassed many accolades throughout her life—an honourary doctorare from the University of Alberta, an Order of Canada, a City of Edmonton park in her name featuring a bronze buffalo.[32] But her true nukutumâ’kewin (legacy) is in the words that people use every day, words like muskêkêw’wiskwew (nurse) and musinahikew’êniw (poet); âyisêni’wak (people) and tayoh’kew (storyteller); and, of course, muske kê’wêyiniw (doctor)—the iskwew mistahi kâ nâpeh’kâsot (heroine) of her pêkis’kwewin (language).

Bruce Cinnamon © 2020

[1] Regarding the quote in the article title: “Metis Elder, cultural advocate passes away.” Terry Lusty, Sweetgrass Writer, St. Albert. Alberta Sweetgrass Volume 4 Issue 6, 1997. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.ammsa.com/publications/alberta-sweetgrass/metis-elder-cultural-advocate-passes-away

[1] All translations are taken from Dr. Anne Anderson’s Métis Cree Dictionary. Edmonton, Duval House Publishing, 1997. This article uses standard text for nêhiyawêwin (the Cree language) words and italics for English translations to emphasize that Cree is the traditional language of the area now known as Edmonton, and English is the foreign language on this territory. This decision is inspired by Christine Stewart’s “On Treaty Six from Under Mill Creek Bridge” in Toward. Some. Air., Banff Centre Press (2015) and Tracy Bear’s doctoral thesis Power in My Blood: Corporeal Sovereignty, University of Alberta (2016).

[2] “Still going strong at 84 years young.” Josie Auger, Windspeaker Staff Writer, Edmonton. Windspeaker Volume 7 Issue 24, 1990. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.ammsa.com/publications/windspeaker/still-going-strong-84-years-young-1

[3] “Dr. Anne Anderson: teacher, author makes good on a promise to her mother.” Cheryl Petten, Associate Editor. Windspeaker Volume 22 Number 11, 1 February 2005. p. 26. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/February%202005.pdf

[4] Profile by Marlaine Metchewais in My Heroes Have Always Been Indians: A Century of Great Indigenous Albertans. Ed. Dr. Cora J. Voyageur, Brush Education, 2018. pp. 29-30. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://books.google.ca/books?redir_esc=y&id=oV10DwAAQBAJ&q=anderson#v=snippet&q=anderson&f=false

[5] “Metis historian and teacher retires at 85.” Judy Shuttleworth, Windspeaker Contributor. Windspeaker Volume 9 Issue 22, 31 January 1992. p. 7. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/January%2031%2C%201992.pdf

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Dr. Anne Anderson Heritage and Cultural Centre – Cultural centre in jeopardy.” John Morneau Grey, Edmonton. Windspeaker Publication Volume 5 Issue 6, 1987. p.1. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2020-01/April%2017%2C%201987.pdf – Dr. Anderson: “Many Native people could not speak their own language, and were punished if they did (residential schools). Now they’re trying to get back to the proper groove so that they can be proud of their language, identity and culture.”

[8] Foreword (written in 1975), Dr. Anne Anderson’s Metis Cree Dictionary. Anne Anderson. Edmonton, Duval House Publishing, 1997.

[9] “Metis historian and teacher retires at 85.” Judy Shuttleworth, Windspeaker Contributor. Windspeaker Volume 9 Issue 22, 31 January 1992. p. 7. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/January%2031%2C%201992.pdf – “I just about died. I didn’t know what I was going to do.”

[10] Ibid. “The schools were terrible. I used to go to the Alberta Teachers Association and a lot of them, you know, they didn’t care. They were prejudiced and lots of things. I used to say your schools are not doing our kids a whole lot of good. They didn’t care if the children studied.”

[11] “Metis Elder, cultural advocate passes away.” Terry Lusty, Sweetgrass Writer, St. Albert. Alberta Sweetgrass Volume 4 Issue 6, 1997. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.ammsa.com/publications/alberta-sweetgrass/metis-elder-cultural-advocate-passes-away – “She fought a long and hard battle with the schools in Edmonton and the University of Alberta to include Cree language instruction in their curricula.”

[12] Metis historian and teacher retires at 85.” Judy Shuttleworth, Windspeaker Contributor. Windspeaker Volume 9 Issue 22, 31 January 1992. p. 7. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/January%2031%2C%201992.pdf

[13] “Dr. Anne Anderson Heritage and Cultural Centre – Cultural centre in jeopardy.” John Morneau Grey, Edmonton. Windspeaker Publication Volume 5 Issue 6, 1987. p.1. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2020-01/April%2017%2C%201987.pdf

[14] “Dr. Anne gets help, money.” Mark McCallum. Windspeaker Publication Volume 5 Issue 8, 1987. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.ammsa.com/publications/windspeaker/dr-anne-gets-help-money – “The government (Native Services) kept promising that they would give me funds to run the place And then all of a sudden, they phoned and said this couldn’t carry on anymore.”

[15] Ibid.

[16] Profile by Marlaine Metchewais in My Heroes Have Always Been Indians: A Century of Great Indigenous Albertans. Ed. Dr. Cora J. Voyageur, Brush Education, 2018. pp. 29-30. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://books.google.ca/books?redir_esc=y&id=oV10DwAAQBAJ&q=anderson#v=snippet&q=anderson&f=false

[17] “Dr. Anderson’s work preserving Cree honored by province.” Heather Andrews, Windspeaker Staff Writer, Edmonton. Windspeaker Publication Volume 9 Issue 1, 1991. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://ammsa.com/publications/windspeaker/dr-andersons-work-preserving-cree-honored-province

[18] “Metis historian and teacher retires at 85.” Judy Shuttleworth, Windspeaker Contributor. Windspeaker Volume 9 Issue 22, 31 January 1992. p. 7. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/January%2031%2C%201992.pdf

[19] Profile by Marlaine Metchewais in My Heroes Have Always Been Indians: A Century of Great Indigenous Albertans. Ed. Dr. Cora J. Voyageur, Brush Education, 2018. pp. 29-30. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://books.google.ca/books?redir_esc=y&id=oV10DwAAQBAJ&q=anderson#v=snippet&q=anderson&f=false

[20] “Metis historian and teacher retires at 85.” Judy Shuttleworth, Windspeaker Contributor. Windspeaker Volume 9 Issue 22, 31 January 1992. p. 7. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/January%2031%2C%201992.pdf

[21] Cree Productions. Métis Nation of Alberta. Accessed 05 October 2020. http://albertametis.com/affiliates/cree-productions/

[22] “Metis Elder, cultural advocate passes away.” Terry Lusty, Sweetgrass Writer, St. Albert. Alberta Sweetgrass Volume 4 Issue 6, 1997. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.ammsa.com/publications/alberta-sweetgrass/metis-elder-cultural-advocate-passes-away

[23] “Educator set out to preserve Cree language.” Kenneth Williams, Windspeaker Staff Writer, Edmonton. Windspeaker Volume 15 Number 1, May 1997. p. 26. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/May%201997.pdf

[24] Ibid.

[25] “Dr. Anne Anderson: teacher, author makes good on a promise to her mother.” Cheryl Petten, Associate Editor. Windspeaker Volume 22 Number 11, 1 February 2005. p. 26. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/February%202005.pdf

[26] “Metis historian and teacher retires at 85.” Judy Shuttleworth, Windspeaker Contributor. Windspeaker Volume 9 Issue 22, 31 January 1992. p. 7. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/January%2031%2C%201992.pdf – “It’s all changing. They say it’ll all be different in another decade. Nearly every decade something changes.”

[27] “Dr. Anne rejects Olympic booking.” Lesley Crossingham. Windspeaker Volume 5 Issue 20, 1987. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.ammsa.com/publications/windspeaker/dr-anne-rejects-olympic-booking

[28] Introduction and Preface. The First Métis – A New Nation. Dr. Anne Anderson. Edmonton, Uvisco Press, 1985.

[29] “Metis historian and teacher retires at 85.” Judy Shuttleworth, Windspeaker Contributor. Windspeaker Volume 9 Issue 22, 31 January 1992. p. 7. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.windspeaker.com/sites/default/files/2019-12/January%2031%2C%201992.pdf – “My son and daughter understand (Cree) but at that time it was very bad to be a Native person, there was so much prejudice and the kids were hurt very much in life. My husband used to say ‘don’t teach the children. I suffered and you suffered because of being Native. Just let them grow up as white people,’ and that’s what we did.”

[30] “Keeping Cree a living language.” Willie Moberg. The Edmonton Journal, 01 September 1970. p. 3. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=gYAb_yFic6IC&dat=19700901&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

[31] “Metis Elder, cultural advocate passes away.” Terry Lusty, Sweetgrass Writer, St. Albert. Alberta Sweetgrass Volume 4 Issue 6, 1997. Accessed 05 October 2020. https://www.ammsa.com/publications/alberta-sweetgrass/metis-elder-cultural-advocate-passes-away

[32] Ibid.