The history of missionaries as they relate to the development of post-contact Canada is long, complicated, and often very emotional, especially when it relates to Indigenous groups, cultures, and identities. For many years, missionaries and their work were praised, and some became celebrated figures in public history, such as Fr. Lacombe, Bishop Grandin, and Rev. McDougall in the Edmonton area. Clearly, the impact of their work and actions are still at play today, and it is vital to acknowledge that the collective actions of missionaries and the religious institutions they represented were devastating to Indigenous communities throughout what is now called Canada.

Individual missionaries undertook individual actions, and when reflecting on the legacy of missionaries in our history, our understandings are deepened when we reflect on both the wider context and the smaller details. For example, when one evokes the name “Rundle” in the Edmonton area, most people tend to focus on Rundle Park along the North Saskatchewan River. Once a landfill in northeast Edmonton, the land is now one of our city’s most beautiful, if bumpy, parks. But where does the name Rundle come from? And who was this person?

Clockwise from left: 1. The sign to Rundle Park, located in the North Saskatchewan River Valley near the Beverly neighbourhood. 2. A Google Maps screenshot of Rundle Park. Note the many locations named after Robert Rundle in this part of Edmonton. 3. The Rundle Family Centre in Rundle Park. Photos courtesy of the ECAMP Team, October 2020.

After 1821, the Hudson’s Bay Company had a monopoly over the fur trade in the northwest and wanted to keep it that way. There was still plenty of profit to be made trading with various Indigenous groups that travelled long distances to trade, and the fewer distractions they had from commerce, the better. However, the Hudson’s Bay Company was still subject to the whims of outside influence. In England, pressure on the company started to mount from Christian evangelical groups to send missionaries to convert Indigenous populations and others in the northwest.

Sensing an opportunity to appease these groups, while also improving public opinion and keeping the Company sympathetic to the British Government, the HBC agreed to send missionaries west. The Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society was chosen for this role. There is no exact reason given for why this group in particular was chosen, but historians have proposed some potential ideas. One possible scenario grouped them as a ‘better’ alternative to the Roman Catholics who had been trying to increase their prominence in the west. Managers within the company worried that if missionaries were successful, then Indigenous peoples would be less likely to participate in the fur trade. Compared to the Roman Catholic Church, the smaller Wesleyan Society had far less influence and power to interfere with Company business.

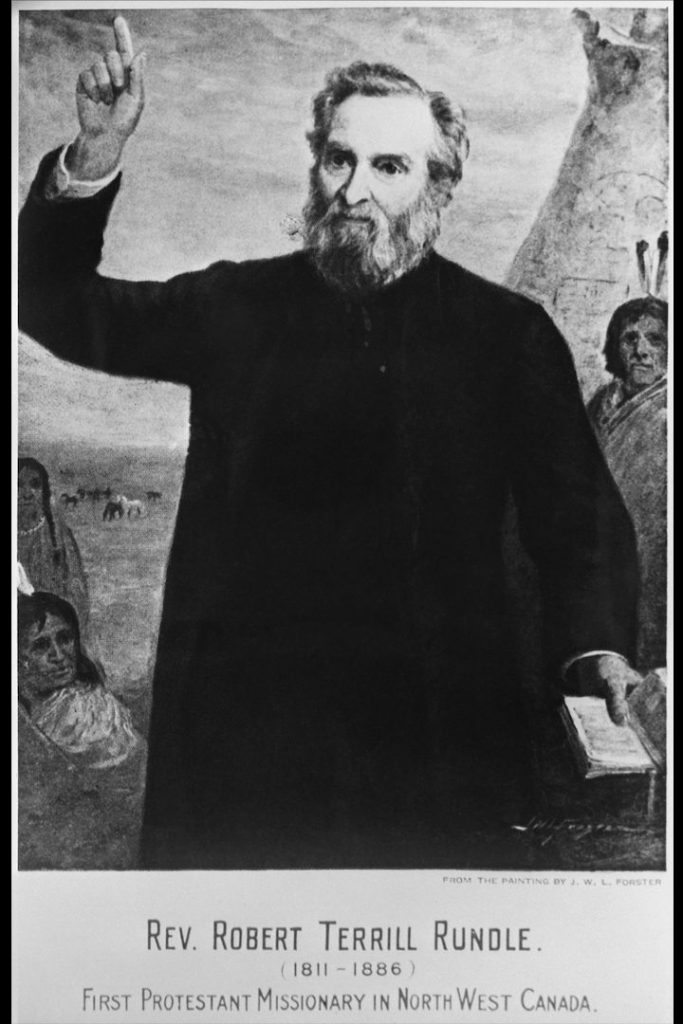

Enter Reverend Robert Terrill Rundle.

Image courtesy of the Glenbow Archives, NA-642-1.

Arriving at Fort Edmonton in the fall of 1840 at the age of 29, Rundle quickly found that his job would be a lot tougher than anticipated. His troubles started in the Fort itself, where he had difficulty getting people to attend his Protestant services because many of the Métis and European labourers were Catholic. He was also shocked to learn many of them worked on Sundays, practiced as the Christian “Sabbath.” While he urged them not to work, his pleas were often ignored by those accustomed to their routine and company men that put the Company first.

Unperturbed, Rundle took his job seriously and was every bit devoted to his religion as he was to the conversion of Indigenous peoples. While the Company would have preferred Rundle to remain at Fort Edmonton, Rundle found that his greatest opportunities to learn and teach came when he left the Fort to meet with the Indigenous peoples in their own camps. This allowed them to choose whether or not to meet with him on their own terms.

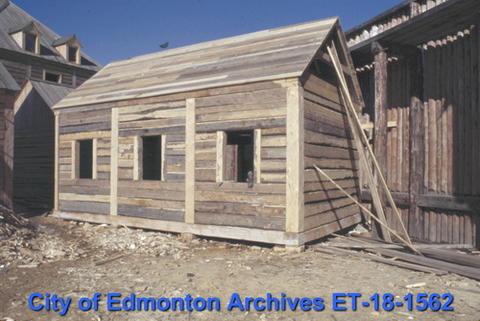

By 1843 a small three-room chapel was built for him; two for his own use, and the other for his sermons. By 1845, he had learned enough Cree and Assiniboine to begin leading services in those languages instead of English. By 1848, he must have left the northwest feeling as though he had accomplished much.

While Rundle was a devoted missionary, his first few years made him quite homesick. He wrote letters home to his brother and sister like clockwork, describing his life, work, and even the most mundane things, such as his chapel’s layout. Unfortunately for Rundle, his siblings were less inclined to communicate. By the fall of 1843, he had only received one letter from them, while he had sent them near-monthly correspondence. His desire for outside contact was clear at this point, as halfway through writing a letter in September of 1843, Rundle noted that the express canoe (used to deliver the mail) had arrived and that he was going to check it before completing his letter so that he could respond to any mail they had sent him. After the break in writing, his continued response was:

‘Well the Express is arrived

Too bad-too bad

Too bad-too bad-too bad

Too bad-too bad-too bad

Too bad-too bad-too bad

Too bad-No letters!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

I am aff. Your brother

R.T. Rundle’

By 1844, he sent a similar letter to his father, bemoaning the lack of contact the two had had during his time in the northwest.

It was perhaps for this reason that Rundle sought other companionship while isolated from his family- the cute and cuddly kind. As it turns out, Rundle had an affinity for cats. On one occasion, when he was travelling in 1846, he opted to bring his favourite cat with him from Fort Edmonton. The cat would prove to be more trouble than it was worth. One fateful morning, Paul Kane (an Irish artist travelling with Rundle) observed what could only be described as a comedy of errors.

“Mr. Rowand, myself, and Mr. Rundell [sic], having determined to proceed to Edmonton on horseback . . . we procured horses and a guide and, on the morning of the 12th September, we arose early for our start. The Indians had collected in numbers round the fort to see us off, and shake hands with us, a practice which they seem to have taken a particular fancy for. No sooner had we mounted our rather skittish animals than the Indians crowded around, and Mr. Rundell, who was rather a favourite amongst them, came in for a large share of their attentions, which seemed to be rather annoying to his horse. His cat he had tied to the pummel of his saddle by a string, about four feet long, round her neck, and had her safely, as he thought, concealed in the breast of his capote. She, however, did not relish the plunging of the horse, and made a spring out, utterly astonishing the Indians, who could not conceive where she had come from. The string brought her up against the horse’s legs, which she immediately attacked. The horse now became furious, kicking violently, and at last threw Mr. Rundell over his head, but fortunately without much injury. All present were convulsed with laughter, to which the Indians added screeching and yelling as an accompaniment, rendering the whole scene indescribably ludicrous. Puss’s life was saved by the string breaking; but we left her behind for the men to bring in the boats, evidently to the regret of her master, notwithstanding the hearty laugh which we had had at his expense.”

In that situation, it would be understandable to only care about yourself and your safety. However, Rundle’s main concern was for his cat, as it was noted later that while he flew through the air, Rundle cried out not for himself, but for his cat.

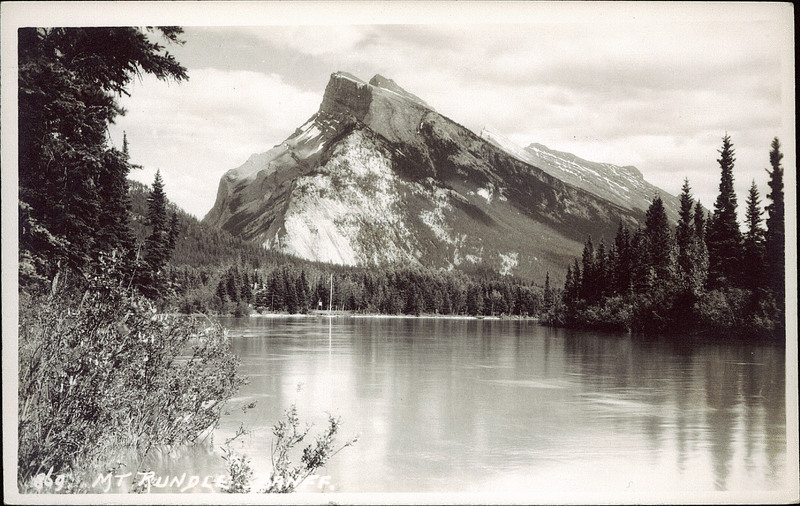

Rundle was only supposed to remain at Fort Edmonton until 1844. However, a replacement for him could not be found, and either due to a sense of duty, religious obligation, or pride, he opted to remain at Fort Edmonton until a suitable replacement was secured. His cause for leaving in 1848 was not due to a replacement, but an injury that required treatment in England. Still, Rundle seems to have become fond of the region; his journal makes that evident, as when he was forced to leave in 1848, it appears that he had every intention of returning (though, ultimately, he did not).

Every missionary that came to the west had different intentions, methodologies, and- ultimately- numerous outcomes. Robert Rundle was active in Western Canada from 1840 until 1848. And while he could not have foreseen the work of his successors, he was one of the first links in a chain that would lead to the establishment of the Indian Residential School System and its devastating legacy. For decades now, questions around the role missionaries played in the colonizing and settlement of this territory have been at play. Like current responses to monuments and place names of “celebrated” public figures, reengaging with the legacy of missionaries gives us the opportunity to learn more about them as individuals and see them for who they were and what motivations drove them.

Neil Cramer © 2020

Sources:

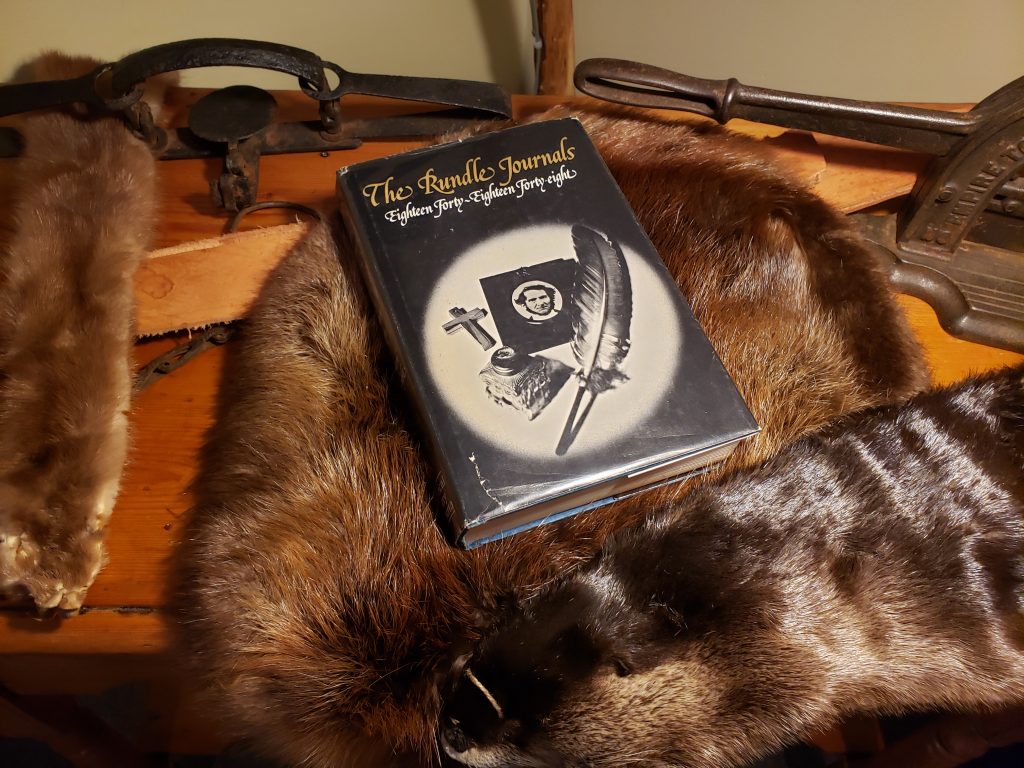

Robert Rundle, The Rundle Journals: 1840 – 1848., ed. Hugh A. Dempsey (1977).

Paul Kane, Wanderings of an artist among the Indians of North America (1859).

James Raffan, Emperor of the North. Sir George Simpson and the Remarkable Story of the Hudson’s Bay Company (2007).