Shortly after entering Emily Murphy Park, which sits on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River between Groat Bridge and the main campus of the University of Alberta, there is a dark grey statue of the park’s namesake. A depiction of Emily Ferguson Murphy (1868-1933) stands sturdily atop a granite base, in the middle of a large piece of concrete. The statue is comprised of a dark metal that suits her Victorian clothing comprising a hat, leather jacket, an ankle-length skirt and some leather gloves holding a book.

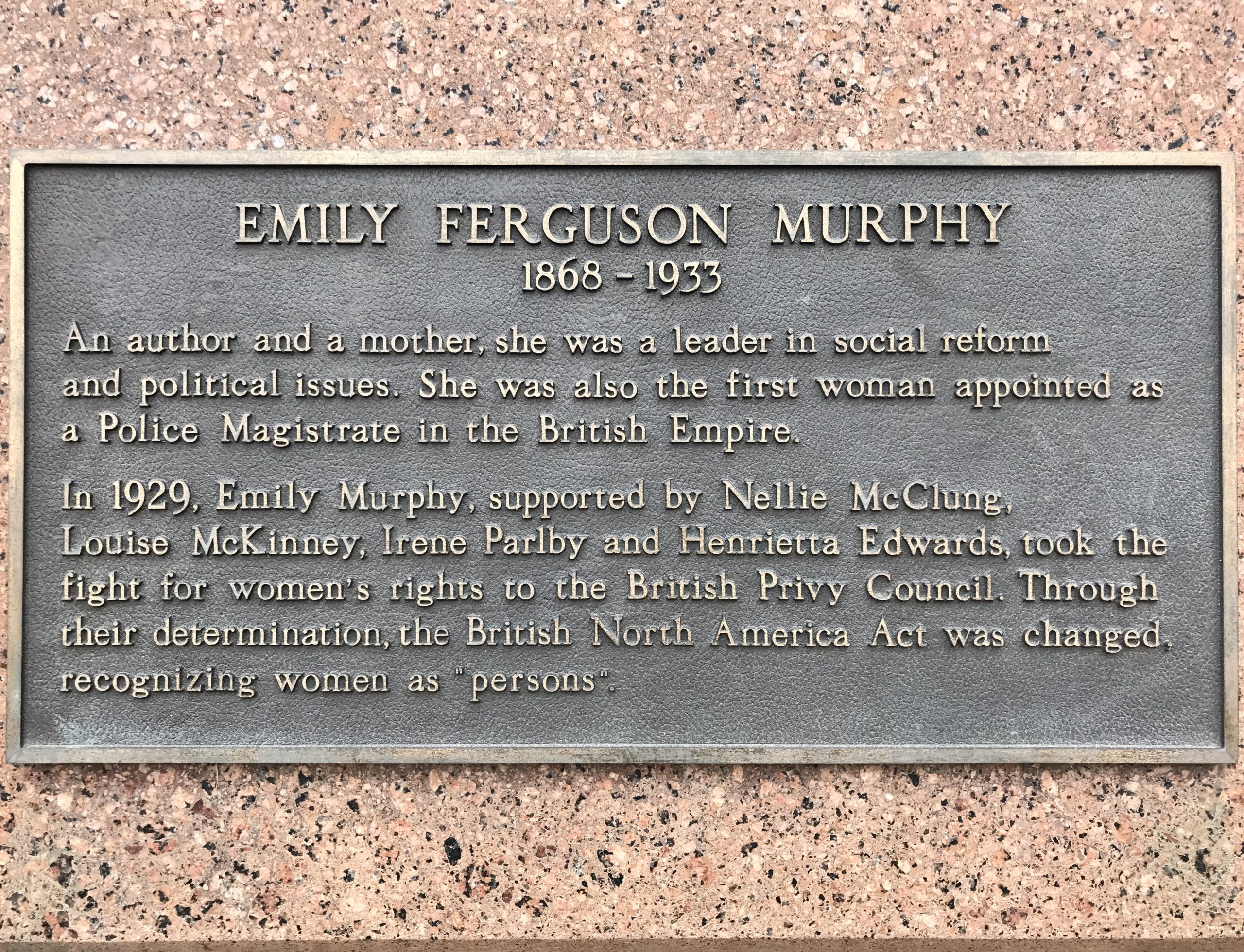

In many ways this is a very conventional historical monument. It reminds present day citizens of the lead role she played as a member of the Famous Five, and their successful fight to have women declared “persons” in Canada and therefore eligible to serve in the Senate. The brass plaque tells us: “An author and a mother, she was a leader of social reform and political issues.” With so much granite and metal, it makes it seem this historical story is immutable and complete.

Left to Right: The sign at the entrance to Emily Murphy Park. Each of the Famous Five have a park named after them in Edmonton’s North Saskatchewan River Valley. Photo courtesy of the ECAMP Team, October 2020. A close-up of one of the plaques from the statue of Emily Murphy. It reads: An author and a mother, she was a leader in social reform and political issues. She was also the first woman appointed as a Police Magistrate in the British Empire. in 1929, Emily Murphy, supported by Nellie McClung, Louise McKinney, Irene Parlby and Henriette Edwards, took the fight for women’s rights to the British Privy Council. Through their determination, the British North America Act was changed, recognizing women as “persons.” Photo courtesy of the ECAMP Team, October 2020.

But like so many historical figures, the life of Emily Murphy is being re-examined and re-evaluated. She is seen today as being more than just an important figure in early 20thcentury feminism and women’s suffrage. Increasingly, historians – amateur and professional – have begun to shed light on her beliefs about racial superiority and eugenics. Since the 1980s, historians have shown how many first wave feminists like Murphy fought for equal rights for predominantly white women, or more precisely, white, educated, upper-class, Protestant women.

In recent years, street protests have sparked public debate about whether we should be heralding the accomplishments of the historical figures celebrated in these monuments and statues. Protests have questioned the racist views of Christopher Columbus, the roles of Confederate generals in propping up slavery in the American south, John A MacDonald’s support for residential schools or, here in Edmonton, Frank Oliver’s federal and provincial political role in backing anti-immigration and anti-Indigenous policies.

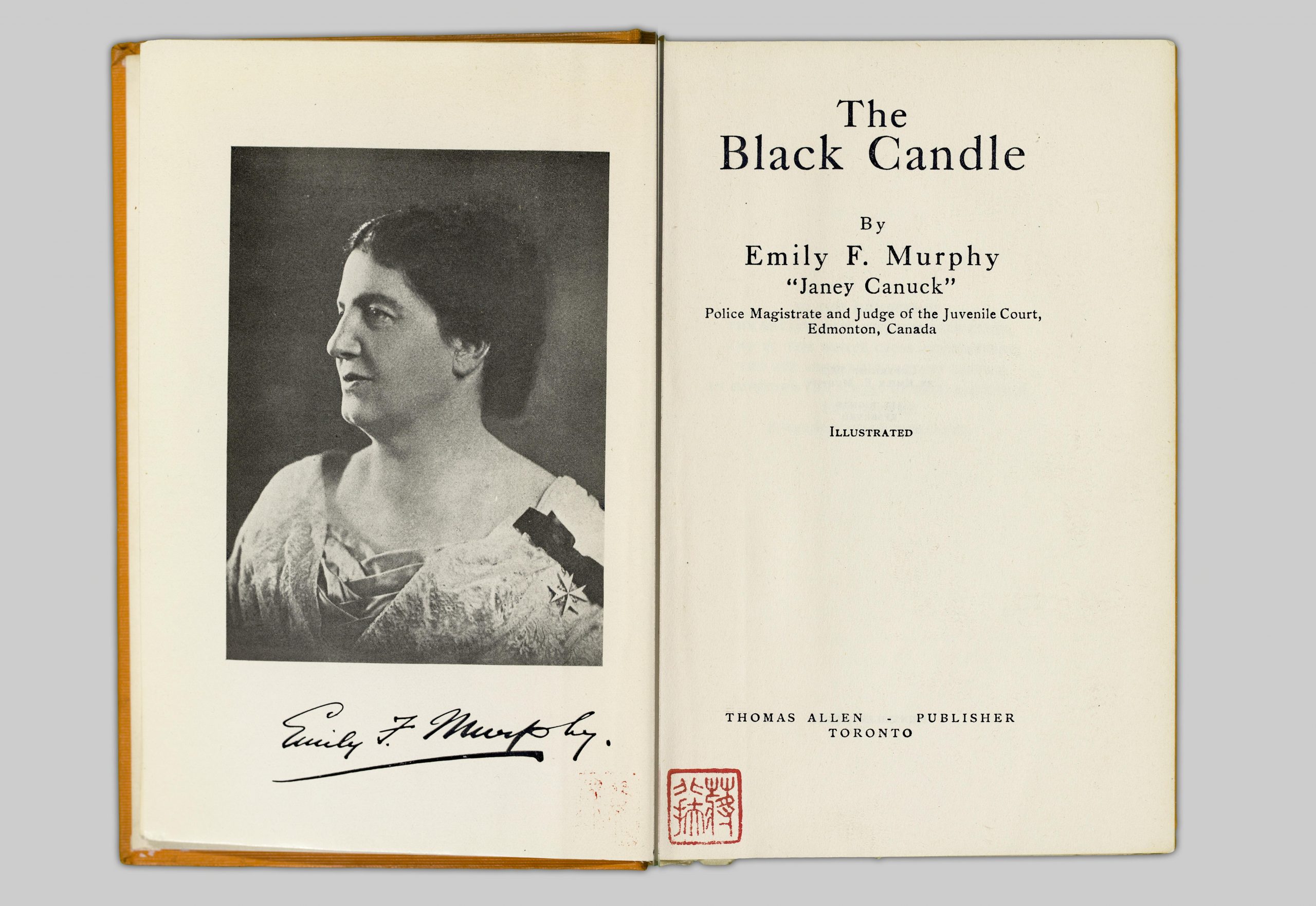

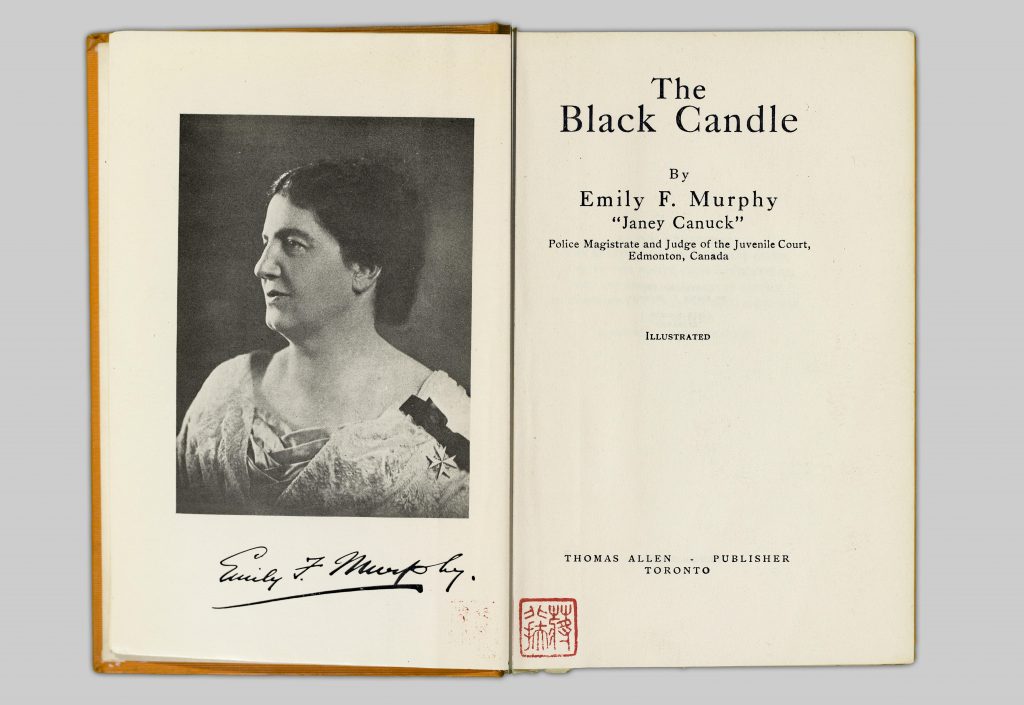

In the case of Murphy, contemporary criticism finds evidence in Murphy’s 1922 book, The Black Candle, where she explores the causes and potential solutions to drug addiction in Canada. Based in part on articles she wrote for Macleans magazine, and during her time as a police magistrate and juvenile court judge in Edmonton, she directs considerable blame towards Chinese immigrants who imported and sold opium and other drugs to unsuspecting local youth.[1]

In 1998, Globe and Mail columnist Jan Wong shocked those attending a Famous Five Foundation charity luncheon in Calgary when she read an excerpt from The Black Candle. Wong, a third-generation Chinese-Canadian, told the audience that Murphy believed Canada’s Chinese were secretly plotting the downfall of the white race through the distribution of opium.

Reading from Murphy’s book Wong said: “It behoves the people of Canada to consider the desirability of these visitors – for they are visitors – and to say whether or not we shall be ’at home’ with them in the future.”[2]

In other parts of The Black Candle, Murphy writes about Black Pullman Porters and accuses them of selling drugs on Canadian trains:

“When it comes to railway porters – Ah well! There are some we know of personally whose liberty is more attributable to their good luck than their good behaviour.”

She describes how these railway porters are involved in the distribution of drugs and even pornography:

“One can hardly imagine anything more dangerous than a filthy-minded drug-addict in charge of a coach of sleeping people, whatever his colour may be.”[3]

Throughout her life, Murphy took on many social issues and causes. One was in the early 1920s, when she supported the efforts of Emmeline Pankhurst who travelled extensively throughout western Canada speaking about the purity of the British race and other topics. University of Alberta Professor Sarah Carter, a specialist in western Canadian history, has written about the relationship between Pankhurst and Murphy. The younger British suffragette and socialist activist visited Canada many times following WWI on lecture tours. In June 1916, Pankhurst spoke twice in Edmonton to overflow crowds and attended a reception at the home of Nellie McClung. In 1920, she decided to stay permanently, continuing to speak about the supremacy of the British Empire and the responsibilities of British (and Canadian) women to guard the purity of the race.

Both activists and early feminists, Murphy and Pankhurst became friends and often shared the podium.

Pankhurst spoke in large and small cities, in theatres, factories, churches, schools, and private homes about the importance of racial betterment, the “disease” of Bolshevism, the dangers of venereal disease, the feeble-minded, and the foreigner. Prof. Carter writes that: “In Canada, Pankhurst’s belief in eugenics came to fruition and crystallized.”[4]

Historians have often connected the ideas of Emily Murphy with Alberta’s embracing of eugenic philosophies. Outside of academic circles, Emily Murphy is often described as a strong, fearless, and heroic activist for women’s rights and social reform.

As a result of Alberta’s 1928 Sexual Sterilization Act, more than 2,800 people were sterilized, ten times more than in British Columbia, the only other Canadian province with similar legislation.

University of Victoria professor emeritus and legal historian John McLaren wrote that Murphy “played an important role in creating a climate of opinion in which this eugenicist initiative became possible.”[5] Contrast these depictions with, for example, the Girl Guides of Canada’s joint campaign with the Famous Five Foundation in 2000 to support a touring exhibit about the Person’s Case even creating the opportunity for Canada’s Sparks, Brownies, Guides and Pathfinders to earn a special crest for learning about the Famous Five.[6]

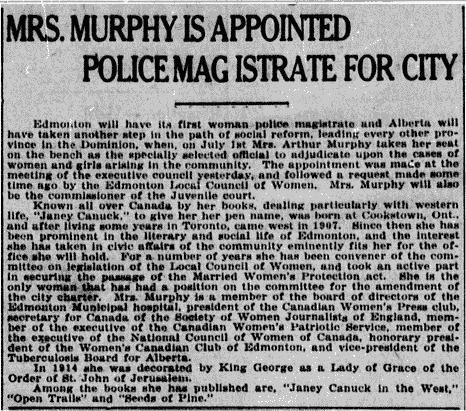

Another example is the Heritage Community Foundation that maintained a website until 2009 that presented a positive image of Murphy that focussed on her life-long work on progressive social reform. The online article, now available on the Alberta Online Encyclopedia, recounted a story where Murphy and her husband were traveling in rural Alberta when they met a homeless woman who was left penniless when her husband sold their farm and abandoned his wife and children. “Much to Murphy’s horror, there was no legal recourse for the woman who had spent 18 years working on the family farm,” the article recounted. [7]Murphy set out to change this situation, and spent several years studying on her own. She worked to convince MLAs to support her cause. In 1917, the Dower Act was finally passed in the Alberta legislature, establishing a wife’s right to one-third of her husband’s estate, although many years passed before it was enforced. This chapter in her life led her to seek the position of magistrate in the women’s court by 1916 and later to join with Nellie McClung, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Irene Parlby and Louise McKinney to change the British North America Act to allow women to be appointed to the Canadian senate.

No historical individual should be reduced to a single viewpoint but, in the case of Emily Murphy, we should certainly revise our assessment of her accomplishments. Yes, her views represent those of the white establishment of her time, but we also need to acknowledge the harm that such views caused, and we need to view her place in history in a more accurate light.

While we need to be more thoughtful than the angry mob that tears down a statue of a controversial figure, we need to include and commemorate the contributions of many other diverse groups and individuals. Our history is more than a bronze monument. It is our collective story, that is under constant reconsideration. Emily Murphy serves as an example that even a progressive activist, who fought fearlessly for women’s rights, can sometimes get it wrong.

Terry Jorden © 2020

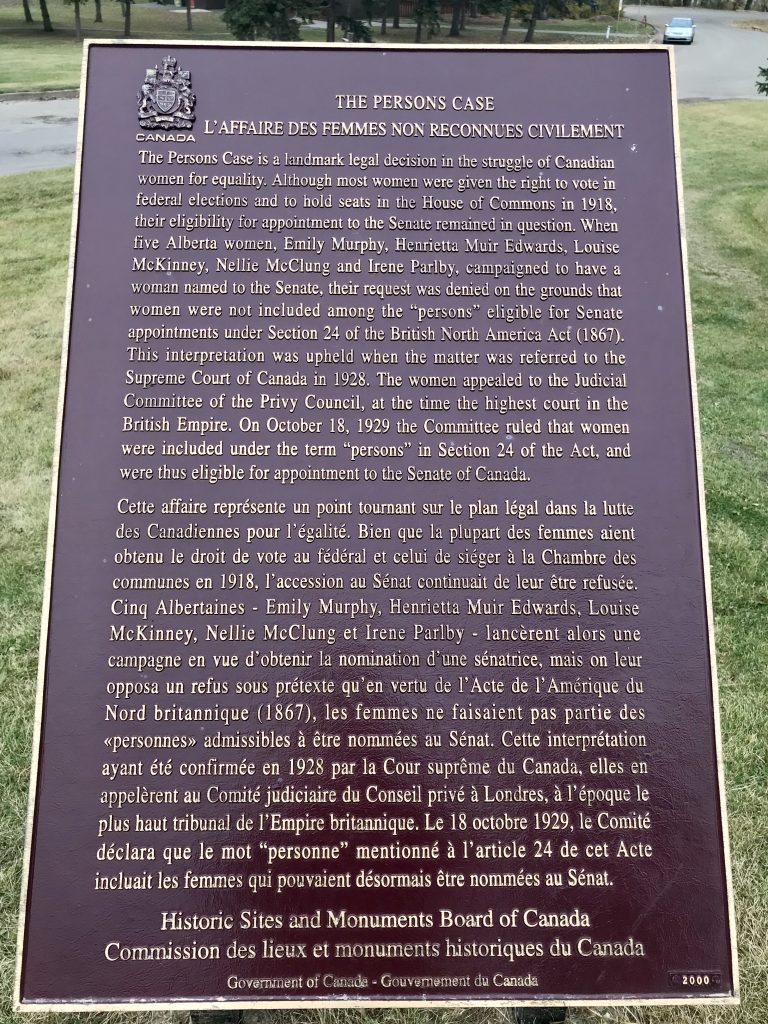

“The Persons Case is a landmark legal decision in the struggle of Canadian women for equality. Although most women were given the right to vote in federal elections and to hold seats in the house of commons in 1918, their eligibility for appointment to the Senate remained in question. When five Alberta women, Emily Murphy, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Louise McKinney, Nellie McClung and Irene Parlby, campaigned to have a woman named to the Senate, their request was denied on the grounds that women were not included among the “persons” eligible for senate appointments under section 24 of the British North America Act (1867). This interpretation was upheld when the matter was referred to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1928. The women appealed to the judicial committee of the privy Council, at the time of the highest court in the British Empire. On October 18, 1929 the committee ruled that women were included under the term “persons” in section 24 of the act, and worth us eligible for appointment to the Senate of Canada.”

Text from one of the commemorative plaques located in Emily Murphy Park, Edmonton Alberta.

[1] Emily Ferguson Murphy (Janey Canuck), The Black Candle (Toronto, ON: Thomas Allen Publisher, 1922), 28.

[2] Joe Woodard, “But She Was a Feminist Racist: A Columnist Has Some Startling Words about the Famous Five,” Alberta Report, May 18, 1988: 38.

[3] Murphy, The Black Candle, 36.

[4] Sarah Carter, “Develop a Great Imperial Race: Emmeline Pankhurst, Emily Murphy, and Their Promotion of “Race Betterment” in Finding Directions West: Readings that Locate and Dislocate Western Canada’s Past. ed. Aritha van Herk (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2017), 134.

[5] Carter, “Develop a Great Imperial Race,” 135.

[6] Andrea Adair, “Brownies Guide girls to the Person’s Case,” Herizons, (Spring 2002): 11.

[7] “Emily Murphy,” The Famous Five, 2004, www.abheritage.ca/famous5.