Rambling up the steep paths of the Whitemud Creek cutbank, a view of Rainbow Valley Park appears along with the distinctive horseshoe curl of the creek below. The area contains busy wide walkways through the ravine across the bridge, a campground, Snow Valley ski hill and the new aerial park, a free-standing high rope trekking tower. But another legacy lies deep underground. Not only is it part of the growth of Edmonton, but it connects me to members of my extended family, immigrants from Poland, before I was born.

The story of Edmonton coal, from transformed plant matter over 280 million years old, began with exposed seams in the cutbanks of the North Saskatchewan River valley. When settlers first came in the 1850s, coal was dug for Edmonton’s blacksmith forges. These gopher hole or drift mines were cut out of the soft soil of the riverbank. John Walter also imported coal from Winnipeg in 1874, but by 1882, there were six commercial Edmonton mines in operation. The great flood of 1899 later shifted most of the coal mining operations to the old town of Beverly until its last mine closed in 1952, the same year a new mine opened in Whitemud Creek.

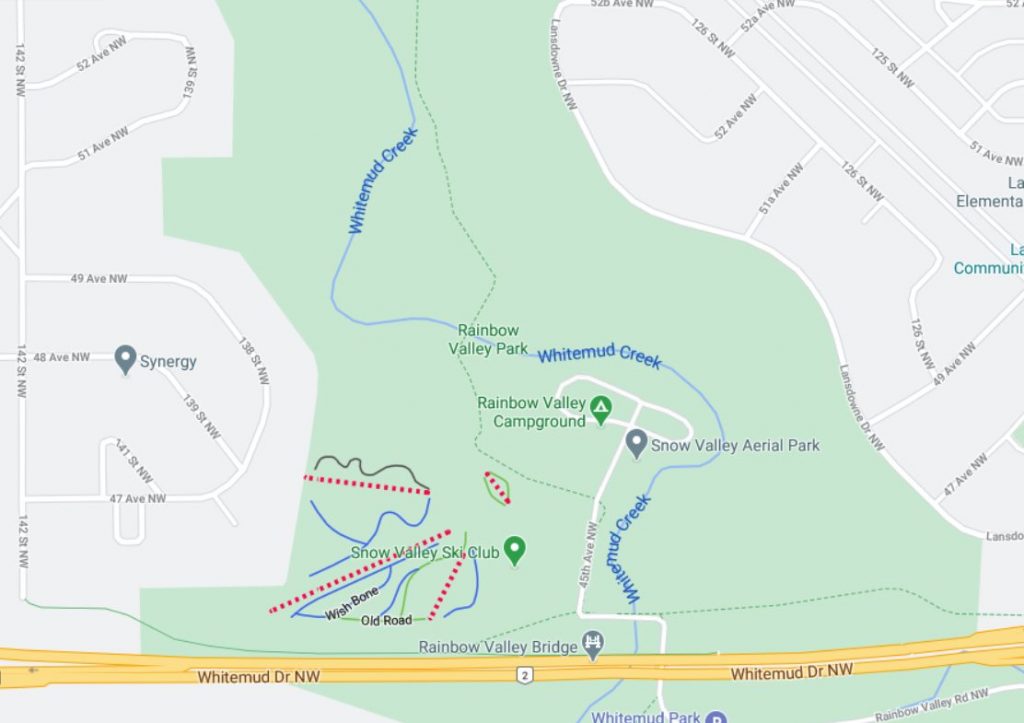

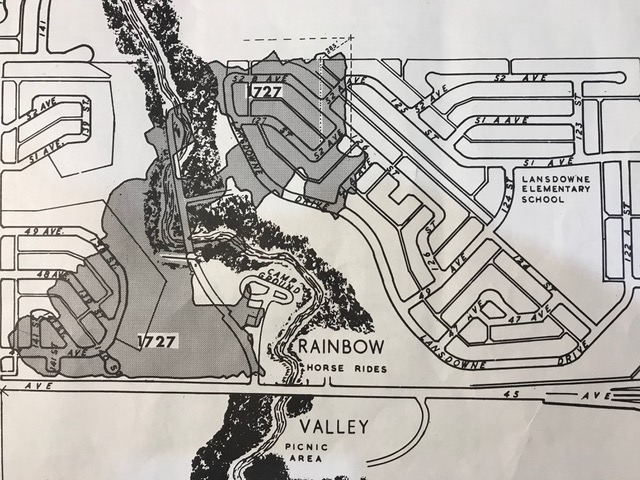

Situated adjacent to Snow Valley Ski Hill and Rainbow Valley Campground, the Whitemud Creek Coal Mine, also known as mine #1727, was the last in Edmonton. The underground mine workings on both sides of the creek, over 67 acres, extended from 45th Avenue on the southside (now Whitemud freeway) to 52B Avenue on the north, and from 142 Street on the west to roughly 126 Street on the east. The slope into the hill was at fifteen degrees, and the air shaft or manway was seventy-two feet. The coal seam was substantial, six to eight feet in depth, so miners could work standing up. In comparison, at many mountain mines, miners worked a three-foot seam on their knees.

In 1964, the roof of the Whitemud mine was reported to be one foot thick, considered “a good roof,”[1] which permitted rooms up to thirty feet, wider than most. From 1952-1970, the mine produced, about 35% of the possible coal in its lease, 273,796 tons. Miners used pick and shovel, and loaded coal into cars hauled by two horses right up until the mine closed.

The Whitemud mine was owned by Waclaw Fridel, his son, Joe Fridel, and his nephew, Joe Lang. Waclaw Fridel, who came to Alberta in 1912, worked in Edmonton and area mines during the first World War, when he was considered an “alien” because his country, Poland, was under Austrian occupation. This meant that he had to report to the police every month, and failure to do so risked being sent to “special labour camps in British Columbia.”[2] As a coal miner in Poland, Fridel’s nephew Joe Lang was exempt from serving in the Austrian Army during the war. After, “because you were only allowed to come to Canada if you were going to a farm,”[3] Joe Lang arrived in winter at another uncle’s farm to work for Waclaw Fridel, who now owned his own mine. Earning five dollars a day, Lang paid back his uncles for his overseas passage by spring.

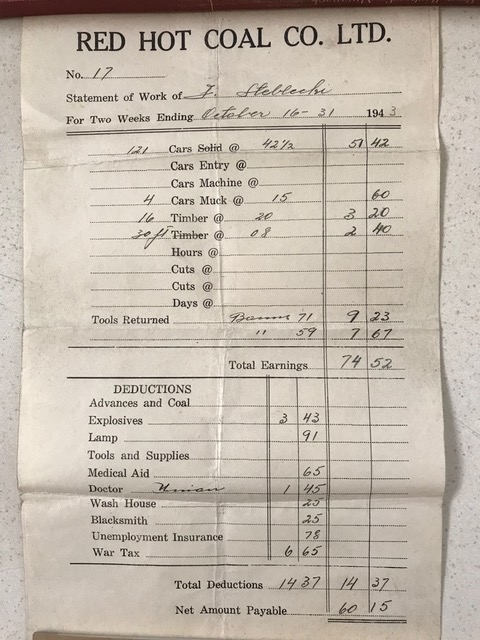

Waclaw Fridel also co-owned the Fridel Coal Company mines in the Rabbit Hill area from 1922 to 1931 and the Red Hot Coal Mine in Forest Heights from 1931 to 1951, where his brother-in-law, my Polish grandfather (Leon Steblecki), also worked as a miner during the war years, when his pay stub included a deduction for War Tax. Including the Whitemud Creek mine, the Fridel family operated coal mines from 1922 to 1970, almost fifty years during the growth of Edmonton.

The Whitemud Creek mine operated behind a single “No Trespassing” sign adjacent to a busy natural area that provided skiing in the winter and camping and day picnic use in the summer. Bert’s Saddle Club, which offered horse rides, was also nearby in Rainbow Valley. The mine lease extended under two neighbourhoods, South Brookside and Lansdowne, and despite “considerable ground movement,” including a cave-in, a squeeze and heaves,[4] a Whitemud Creek Bank Stability study prepared in 1974 cited “no evidence that the coal mining activity north of 45th Avenue affected the slope stability of the creek valley” with the blanket proviso that although “coal mining action can result in increased fissuring of the overlying soils” and can “have a beneficial effect in improving drainage conditions,” it “in some cases might be expected to reduce the stability.”[5] Speculations also included that “the workings now are probably water-filled.”[6]

Pausing on the steep embankment today, overlooking the sharp curve of the water below, the sound and activity of the Whitemud Creek mine can only be imagined: coal cars pulled up by horses on metal tracks, chunks of black coal dumped onto the conveyor belt, sent up to the tipple to be sorted, and down again to waiting trucks. I learned to ski at Snow Valley as a preteen, and while I made tracks on the white snow above, black rock may have come rumbling out of the mouth of the hill beside. I never noticed.

But I do remember, as a younger girl, going for a summertime ride with my James Dean lookalike uncle, in his baby blue convertible, to see the mine where some of our Polish relatives worked. Joe Lang’s brother, Vince, lived in a white house on the mine site and cared for the haulage horses. I watched the horses coming up the dark inside slope to the mine entrance, pulling cars full of coal. I thought the horses were very brave. I asked the miner leading them along if the horses were happy to come up into the air, the light, and the green, and he said, “No, they like it underground. They’re used to it.” That surprised me. Beyond the opening was dark and dust, a black hole.

In the hundred years of coal mining in Edmonton, 160 mines and prospects covered 3260 acres and produced 15 million tons of coal. Edmonton coal was sub-bituminous, which burned long and bright with low ash, ideal for home heating in the first half of the past century. For about twenty-five years, the second largest industry in the Edmonton area (after agriculture) was underground coal mining. People employed by coal mines and protected by the Coal Mines Act numbered 1,571 in 1921, but by 1956 there were only 58 active workers at mine sites.

After the discovery of oil at Leduc in 1947, Edmonton households gradually converted to gas, streetcars to electricity, and railways to diesel. In addition to readily available gas and diesel in the following decade, the strip-mining operation and coal-powered generator at Lake Wabamun, built in 1953, supplied electricity. The market for sub-bituminous coal, mostly bought by Nisku area farmers, dissipated, and development of communities near the Whitemud Creek mine site grew, as Joe Lang writes, “the city was moving closer and all of Edmonton and surrounding areas were now using natural gas.”[7] In addition, far greater quantities of coal were available by surface mining, requiring corporation and extensive machinery, huge water resources, massive land reclamation, and giant coal-powered generators. The days of a miner shovelling to fill and tag a coal car for per unit pay were over. The closure of the Whitemud Creek Coal Mine in 1970 marked the end of underground coal mining in Edmonton.

Katherine Koller © 2020

[1] Taylor, 5.

[2] Matejko, 328.

[3] Matejko,121.

[4] Taylor, 5.

[5] Hardy, 46.

[6] Taylor, 5.

[7] Matejko,122.

Sources

Alberta Energy Regulator Coal Mine Atlas. 2015. www.aer.ca/documents/sts/ST45-CoalMineDataListing.pdf.

Campbell, J.D. Catalogue of Coal Mines of the Alberta Plains. Edmonton: Research Council of Alberta, 1964.

Coal Mine Atlas: Operating and Abandoned Coal Mines in Alberta. 2nd ed. Calgary: Energy Resources Conservation Board, 1988.

Hardy, R.M. Whitemud Creek Bank Stability Study. Edmonton: R.M. Hardy and Associates, 1974.

Matejko, Joanna, ed. Polish Settlers in Alberta. Toronto: Polish Alliance Press, 1979.

Taylor, Richard Spence. Atlas: Coal Mine Workings of the Edmonton Area. Edmonton: Bulletin- Commercial Printers, 1971.