Growing up, Alice Mailhot set her sights on being an engineer like her father. Perhaps Zepherin Mailhot’s life in frontier engineering—charting the Canadian Pacific Railway westward and supervising waterway projects such as Edmonton’s Low Level Bridge—appealed to his petite daughter’s can-do spirit. In their family, Dad’s workday tales (likely spun in French) included outfoxing bears, guiding the RCMP in search of Louis Riel, and using a spider’s web as crosshairs for a surveyor’s transit. But this was the early 1900s, and regardless of how interested Alice was in the profession, no engineering program would accept a woman.

Choosing architecture as a next-best, Alice applied to the in Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, where she could board with cousins. Admitted in 1907, she was the lone woman in her class. Three years later, on May 25, 1910, Alice became the first woman in Canada to hold a diploma in architecture.

Does that accomplishment make Alice Mailhot (or Malhiot, as some spelled it) Canada’s first female architect? Read on and decide.

Registration woes

At first, Alice did drafting for her father, who was laying out municipalities and irrigation ditches from a home base in Calgary. She became “Alys” in those years, her dress elegant, her dark wavy locks topped by a distinctive hat. The name may have reverted to Alice over time, but she never lost that sense of style.

In 1914, she traveled to the University of Alberta, then home to a fledgling School of Architecture, to write the exam required for registration with the Alberta Association of Architects. Decades later, her son Wally learned of his mother’s quest for accreditation while reading his grandfather Zepherin’s memoirs. Eager to learn more, Wally searched through Edmonton Journal microfiche and hit the jackpot with the July 3, 1914 edition:

Miss Alice C. Malhiot of Calgary has successfully passed her examination at the University of Alberta, in the architecture course, and is now an association member of the Alberta Association of Architects.

Scrolling ahead in idle curiosity while savouring that news, Wally stopped short at the following correction, published three days later:

As a matter of fact, Miss Malhiot, who they say, made a very plucky try at the full course, passed only in the branch of sanitary science. Undiscouraged, this little French girl, whose home is in Calgary, intends coming up again next year, at which occasion her complete success will no doubt be assured. – A.M.

There’s no evidence Alice wrote the exam again, or that she ever registered as an architect.

“That may kill your whole story,” Wally mused while sharing memories of his mother for my research on groundbreaking female architects. “I could say she was the first woman architect, but I can’t say she was the first woman registered architect.”

If she had passed that exam, would Alice have been allowed into the Alberta Association of Architects? I still wonder. Less than a decade later, when Marjorie Hill became the first Canadian woman to pass, the association created a new internship requirement that delayed her registration for another five years.

Clockwise from left: 1. Alice Ross, date unknown. 2. Photo of a family scrapbook. 3. Alice with Hugh Ross during their courting days in Calgary, 1913. Photo provided by the author.

Lumbering years

Unregistered, and unable to find employment with an architectural firm, Alice Mailhot worked as secretary for the Alberta Lumber Company (later Revelstoke), while also drawing up plans for customers buying lumber. That’s where she met Hugh Vivien Ross—and in her version of the story, chose him as her husband. Running a Revelstoke lumberyard in Waldeck, Saskatchewan at that time, Hugh regularly hopped the Canadian Pacific to Calgary—for pleasure as well as business, once Alice entered the scene.

Alice and Hugh married on October 18, 1917, and headed to Waldeck, tin cans clattering behind the car. With electricity and running water left behind, household duties displaced architecture for Alice—especially as the family expanded to include three sons and later two daughters. Meanwhile, Hugh was transferred to lumberyards in Alberta, and the family followed to Coronation, then to Francophone Bonnyville (where Alice’s fluent French became an asset) and finally to Beauvallon.

Duffield days

Then came Black Thursday: the stock market crash of October 1929. Hugh lost his post in Beauvallen to the boss’s son and, with jobs scarce, took over The Duffield Trading Company, west of Edmonton on Paul Band land. They moved in convoy, growling through the muck for two days on a journey that would take mere hours today.

As the Great Depression settled in, the store barely made a living as bartering and near-worthless prosperity certificates replaced cash. The Ross’s radio stood silent for want of a $3 battery. Their car sat in the garage, jacked up. Oil and kerosene replaced the portable lighting plant.

Despite those reduced circumstances, Alice became a prime mover in Duffield’s social life, her little-used drafting table always at the ready. Active in the local Catholic congregation, she led the work of dismantling and moving a church building from Stony Plain—then reassembling it, piece by piece. She also drew up plans for a new community hall. “She liked to keep her hand in it,” Wally said.

Left: Alice Ross with her father, Zepherin Mailhot, and daughter Betty, 1937. Photo provided by the author. Right: Alice with her daughters, Elizabeth (left) and Theresa, 1937. Photo provided by the author.

The 1940s brought two sudden, heart-rending deaths. Donald, the Ross’s eldest, crashed in 1941 while training as a pilot for the Second World War. Three years later, Hugh collapsed while signing in to Edmonton’s King Edward Hotel, fatally attacked by his long-ailing heart. Still undaunted, Alice ran the Duffield store for a few more years, then sold the business and moved to Edmonton with her two daughters.

Ross Home Plans

It was in Edmonton, at age 57, that Alice Ross finally made architecture her main pursuit.

Initially, she designed homes for hardware store owner George Prudham, who was developing farmland southeast of downtown into the Strathearn neighbourhood, taking advantage of a post-war, oil-fueled demand for housing.

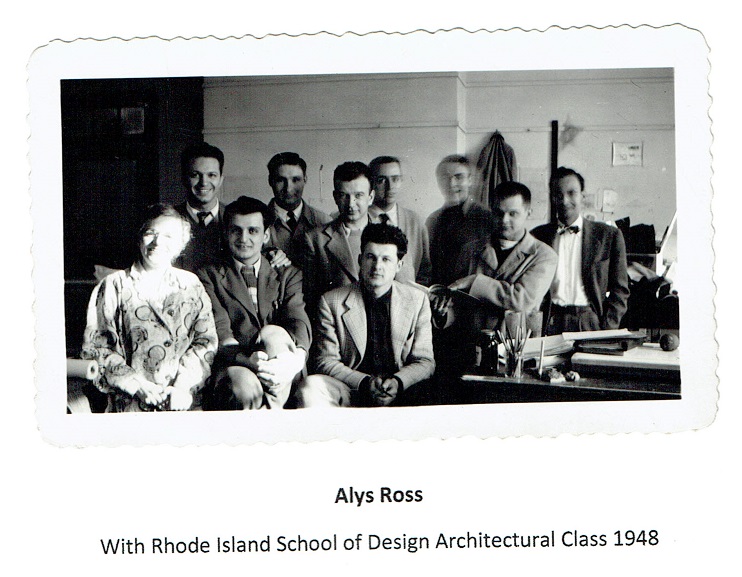

A summer’s work persuaded Alice to upgrade at the Rhode Island School of Design. Leaving the girls behind, she took two courses in 1947, then traveled a circuitous route home to glean more ideas.

Back in Edmonton, Alice launched Ross Home Plans. Employing a concept she discovered while away, Alice developed a catalogue of house designs and invited clients to choose and customize their favourite. The local newspaper expressed high hopes for the venture: “With Edmonton’s home building setting a new Canadian housing record this year, Mrs. Hugh V. Ross has chosen an opportune moment to specialize in home designing.”

The article also provides glimpses of Alice’s design priorities. Ideally houses should have “character,” not be “crowded into too small lots,” ensure southern exposure and optimize the use of sunlight, she said. “If our young people are to enjoy and be content with their homes in the future, they must have distinctive homes with proper landscaping and settings.” For rural buildings, she recommended concrete blocks “so the farmer could start his home himself with this cheaper, fireproof material.”

Left: A flyer featuring the Jasper House, one of several design options available through Ross Home Plans. Right: The Banff, an Alice Ross design intended for rural living. Images provided by the author.

After initially renting a home and sharing a downtown office with her son Gerald, Alice purchased a lot at 9051 90 Street, putting the property in Gerald’s name when the bank refused her a mortgage. Plans for that location still exist in the Edmonton Archives, but with a puzzling label: “Designed for Mr. Hugo Scharfenberg; By Ross Home Plans; 9816 101A Avenue.” Was this Alice’s home, or not? The same Hugo Scharfenberg is mentioned in her diary, with a notation that the house was transferred from Sharfenberg at a cost of about $5,000. It seems Alice’s home, or at least its design, was originally for a client.

Typical of a semi-bungalow, the 28’x26’ home had a main floor plus a smaller upper floor carved out of the attic. Both the second floor and the basement became rental suites to help pay the mortgage. Alice set up her drafting table in the living room and, thus situated, ran Ross Home Plans for nearly two decades.

Although Ross Home Plans specialized in houses, Alice also designed some larger projects. A survey of post-war Edmonton architecture by Ken Tingley, David Murray and Marianne Fedori names a wartime project for the National Housing Scheme as well as several structures completed in 1949: Mills Motors Ltd. (10050 108 Street), Builder’s Supplies (10771 101 Street), Miller Lumber (10460 111 Street), the Windsor Park Community League (11840 87 Avenue).

Clockwise from left: 1. Alice Ross, 1958. 2. Alys Ross & Gloria in Calgary, 1962. 3. Terry, Betty & Alys Ross, 1953. Photo provided by the author.

Alice never lost her steely backbone. In Wally’s words, “She was spunky, a no-nonsense gal. A very modern woman, actually. And she had a great sense of humour.” He continued, “She never drove a car. But then she had a stroke and she had a hard time getting around. So she said ‘I’m going to have to get a car.’”

Alice made it through driving lessons and booked her test. But when her examiner saw that her left leg dragged and her left arm could barely move on its own, he questioned whether she belonged behind a wheel. “Now young man, I have to drive a car,” she replied. “I can’t walk, with my leg the way it is. I need a car.”

“Pure logic, you see,” chuckled Wally. “So he passed her, and she got her licence.” For a son who regularly served as his mother’s chauffeur, her success was a mixed blessing.

In the end, it was a car that killed Alice Ross—but not as you’d expect. She scraped her leg on some metal when getting in; the resulting infection caused a blood clot that eventually migrated to her brain. Her granddaughter came home from school that day to find her slumped over her drafting table, at work until the end. It was an easy death, Wally assured me. Easier than the life that diverted her so long from her chosen career and then left her a widow. “I’ve often thought it was a little bit of a tragedy she didn’t have a better life.

“I think she was a bit of a pioneer,” Wally added. “The way I put it, she walked a path no other woman had dared to walk.”

© Cheryl Mahaffy, 2020

P.S. When I began researching Alice Ross, her home office still stood at 9051 90 Street. It has now been replaced by a skinny infill, another piece of our heritage erased.

Heritage photos courtesy of the Ross family; others by Cheryl Mahaffy.

Sources

Ross, Clyne and Rocque families—interviews, letters, and other previous writing, photographs, newspaper clippings, artifacts.

One of Alice Ross’s five-year diaries, covering the early 1950s, lent by her daughter Theresa.

Hills of Hope, local history including Duffield. Spruce Grove, Alberta: Carvel Unifarm, 1976.

The Practice of Post-War Architecture in Edmonton, Alberta: An Overview of the Modern Movement, 1936-1960. Essay for the preparation of the Modern Inventory of Historic Resources for the City of Edmonton, Ken Tingley, David Murray and Marianne Fedori, Jan 5, 2013.