At the centre of Edmonton’s river valley system sits William Hawrelak Park, an “emerald oasis” that plays host to ice castles and Shakespeare festivals, small family gatherings and the Edmonton Heritage Festival.

What Edmontonians heading into the park may not be aware of is the namesake behind the park: an incredibly popular mayor who sat in the big chair for a dozen years between 1951 and 1975. He was also forced to leave the mayor’s seat twice for using his position as mayor to benefit himself financially, once resigning and once being removed by the Supreme Court of Alberta.

Born in Wasel, a small hamlet northeast of the city, Hawrelak spent his early years building up a political backing and getting involved in a number of initiatives. He was President of the Alberta Bottlers of Carbonated Beverages, President of the Alberta Farmer’s Union, President of the Edmonton Federation of Community Leagues and Finance Chairman of the Trans-Canada Highway Association.

In 1948, Hawrelak dipped his toe into the city’s political arena, making his first run for city council, falling short of a spot by 1,500 votes. He broke into civic politics a year later, substantially increasing his vote total and landing himself a spot on council. It was just a short jump into the city’s top job.

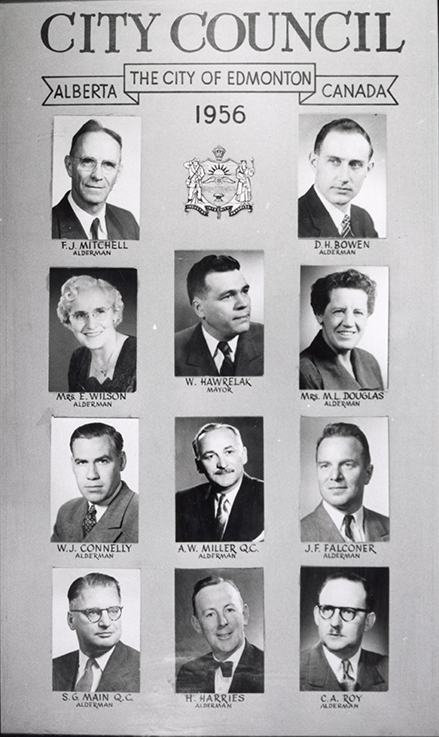

In his first run at the mayor’s chair in 1951, Hawrelak trounced incumbent Sidney Parsons, winning by three times the number of votes as the sitting mayor. He would spend the next eight years as mayor, winning by acclamation in 1953 and 1955 before facing a challenger in the 1957 civic election. Taking almost 65 per cent of the vote, Hawrelak walked into his fourth straight mayoral victory. His position as mayor seemed unassailable.

Then, in 1958, it all started to crumble around him. A petition circulated and was presented to council claiming that “the affairs of the City of Edmonton are not being conducted in an efficient and businesslike manner.” Allegations in the petition included that the sale of city land was not being done with fair market prices, that annexed land was being bought and sold by speculators for ridiculous profits, and that little effort was being made to purchase equipment at fair market value.

After a somewhat opaque internal investigation, council asked the province to step in to lead the investigation in early 1959. The premier appointed Justice M.M. Porter to look into dealings at the city. The investigation found Hawrelak guilty of “gross misconduct” on a number of land deals, and that he had failed to disclose his interests and involvement in transactions involving the City. In his report, Porter said the mayor was “serving two masters at the same time” and recommended the city look into “the city’s right to recover the mayor’s gains in the recited transactions.”

Hawrelak tendered his resignation the day the report was presented to city council. While he never denied the specifics of the report, he didn’t take responsibility for his actions. Contrition, apparently, was not part of Hawrelak’s vocabulary. In a statement to council on the day he resigned, Hawrelak took a shot at Justice Porter and his investigation.

“Contrary to the implications inherent in the report, any private transactions that I had were not with the City and did not involve any City funds or land. The principle which has apparently been applied and which seems to flow from this report, is that a person, upon accepting public office, must relinquish and avoid all private business ties. I believe in electing me to the office of mayor, the citizens of Edmonton expressed a desire to entrust this position to a businessman and that there was no need to divest myself of this status as long as my business dealings were not transacted at the expense of the City of Edmonton.”

The city would sue Hawrelak for $100,000, the amount the mayor profited from his land dealings; that’s equal to almost $1 million in 2020.[1]

But he wouldn’t be out of municipal politics for long. Hawrelak won both the 1963 and 1964 mayoral elections, a mere four years after resigning from the job he loved. The two elections were held back to back in order to align all aldermen and mayor elections into two-year cycles. The 1963 contest was close, but Hawrelak returned to form in 1964, taking almost 60 per cent of the vote.

Then in 1965, Hawrelak again ran into trouble with land deals. A company he was part owner of, Sun Alta Builders Ltd., entered into a land deal with the city in 1964. The City Act limited the mayor and aldermen to a 25 per cent ownership stake in any firm that enters into a contract with the City. Hawrelak held a 40 per cent stake in Sun Alta at the time. Hawrelak was caught on a technicality.

In a court challenge to the mayor’s eligibility to hold the office, Chief Justice C.C. McLaurin said, “I am still unable to comprehend what valid defence has been offered against the charge that the mayor was party to an agreement under which money was payable by the city.” McLaurin estimated the mayor’s profit from the deal and subsequent share sale was close to $85,000. The city again sued Hawrelak for the profits on his land deals.

While he lost his appeal to be reinstated, a 1975 Supreme Court of Canada decision ruled that there were no profits for Hawrelak for return.

Twice Hawrelak was mayor of Edmonton, and twice he was forced to leave office over questionable deals he made for his own profit, using his position as mayor to benefit himself. Both times, all of the information was in the public domain, available to all Edmontonians and all of Hawrelak’s political challengers.

Despite his long history of back room deals and questionable conduct, Hawrelak was again re-elected as mayor in 1974, romping to a big win. The headline the morning after the election blasted “Hawrelak crushes opponents.”

That’s not to say Hawrelak was an invincible politician. He twice ran for federal politics and lost both times, once while he was mayor in 1957, the second time in 1968. He ran for the mayor’s seat in 1966, losing the vote to Vincent Dantzer by about 10,000 votes, while still securing 44 per cent of the votes. One year after being thrown out of office, more than 55,000 Edmontonians still voted for him to be their mayor.

Mayor William Hawrelak speaks with former Lieutenant Governor Grant MacEwan, January 29, 1975. Photo courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives, EA-804-50.

Heritage Days at Mayfair Park, now Hawrelak Park, in 1980. Photo courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives, ET-28-1687.

His resignation and removal from office were front page news and made political waves across the prairies. The final Porter commission report from 1959 was available in the Edmonton Journal. His political opponents reminded Edmontonians time and again about the blemishes on his record. But it didn’t stop Edmontonians from loving Hawrelak and for voting him time and again.

Hawerlak died in office in November 1975, serving less than half of his three-year term. Thousands of people paid their respects as his body lay in council chambers. City council voted to change the name to William Hawrelak park in 1976.

Justin Bell © 2020

[1] Calculated using https://www.in2013dollars.com/canada/inflation/1959?amount=100000. Actual amount $880,000.