Disclaimer: Due to the importance around the legal designation of Indian status, this article sometimes uses the term “Indian” to refer to Indigenous people where legally applicable and relevant, or part of a historical quotation.

When Nellie Makokis married Elmer Carlson, it only took 18 days for the Government of Canada to inform her that she was no longer a status Indian.[1] It would take her over 18 years of activism to reclaim her treaty rights, and to help return those rights to more than 160,000 disinherited Indigenous people across Canada.[2]

Under Section 12(1)(b) of the Indian Act, an Indigenous woman lost her status if she married a non-status Indian, a Métis, or a non-Indigenous man.[3] Although Elmer Carlson was a direct descendant of the Cree chief and Treaty Six signatory Kehewin, and had grown up on the Kehewin Cree Nation reserve, this ancestry came from his mother Helen, who had lost her own status – and that of her children and all her descendants – when she married Swedish immigrant August Carlson.[4] Because of this “mixed” heritage, Elmer was considered Métis by the federal government[5] and by marrying him, Nellie lost her status as well.

On the other hand, if a man with Indian status married a non-status woman, she and all her descendants would become status Indians, entitled to the treaty rights that had been stripped from Nellie and other Indigenous women: the right to live on their reserves, to receive the annual treaty payments to which they were entitled, to own and inherit property, to participate in local politics and vote for band councils and chiefs, to access education and health benefits for themselves and their children, and to be buried in their home communities.[6]

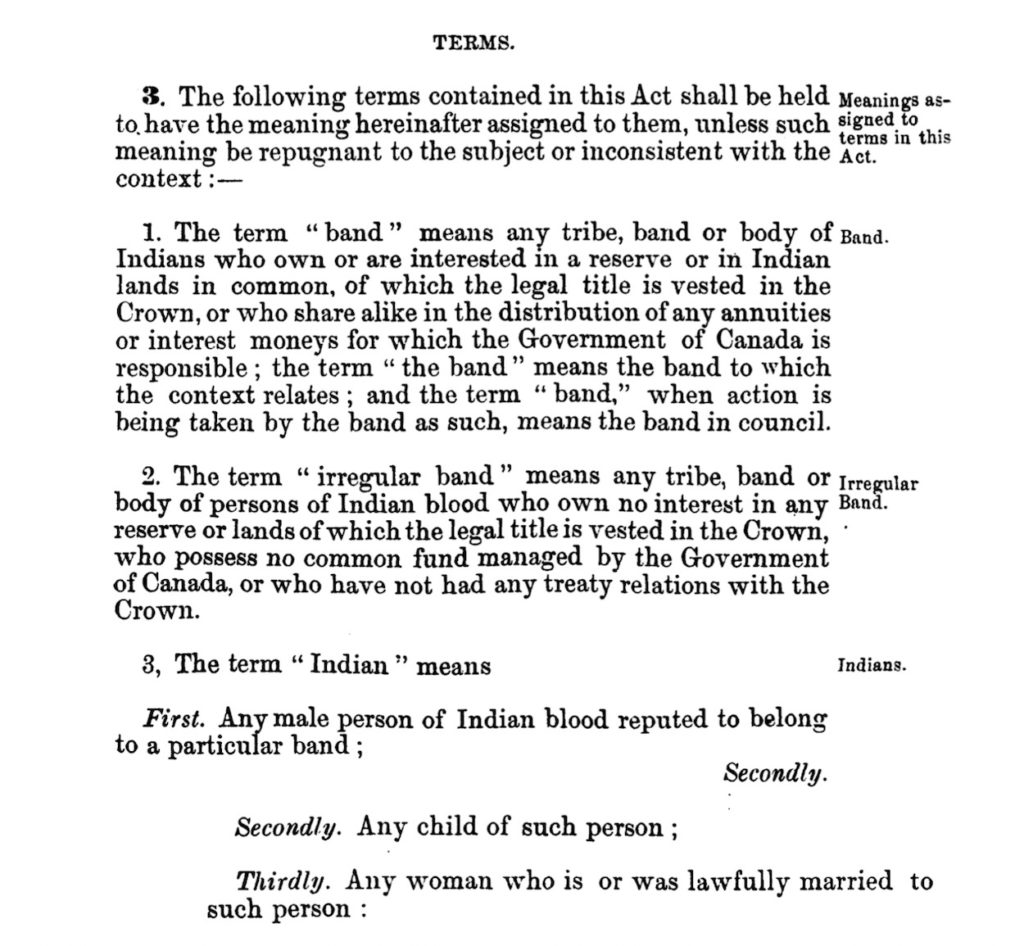

This blatant sexism of Section 12(1)(b) followed years of gender discrimination stemming back to the original Indian Act of 1876, which defined an Indian as “any male person of Indian blood” and his wife and offspring.[7] The federal government maintained lists of Indigenous people for decades, but amendments to the Indian Act in 1951 created the national Indian Register, a list of all status Indians in Canada. Local Indian Agents working for the federal Department of Indian Affairs had unchecked authority to remove anyone they wished from the band membership lists, and they used the threat of removal to silence any dissent.

But Nellie Carlson was not someone who would just roll over and accept an unfair status quo. When she was five years old, she was sent to the Edmonton Indian Residential School in St. Albert, where she was subjected to horrific abuse for nine years. She emerged physically and psychologically wounded. Her traumas, experiences and the things she witnessed gave her a deepened understanding of the systemic injustices of the world and a resolve to fight back against bullies and oppressors.

“I cannot see injustice now and do nothing. I have to act,” she said later.[8]

One time, on a train to Ottawa to hear the result of an important court case, Nellie saw a young man harassing a young Indigenous woman. She pushed him down in his seat and told him that she would put him in an “Indian death hold” (a term which she made up on the spot) if he didn’t leave the woman alone.[9] She was a volcano of determination, erupting whenever anyone tried to intimidate her – “a tiny woman, almost like a little bird, fiery and not afraid to stand up and be heard,” according to friend Maria Campbell, a fellow activist and writer.[10]

When she was told by her doctor that there was a clause in the Indian Act that said that if she spoke out against the Act she could be taken off the band list or prosecuted, Nellie pre-emptively took herself off the Saddle Lake band list. When she visited the Indian Agent’s office and announced that she would be removing her name, the Agent shouted: “Get this damn Indian woman out of here!” Without skipping a beat, she responded: “See! You called me an Indian woman! That is what I am… I’ve come here to tell you. I’ll be back to fight for my treaty rights.”[11]

And Nellie did fight, moving to Edmonton and founding an advocacy group called Indian Rights for Indian Women (IRIW) with a handful of other disinherited Indigenous women. These included her cousin Kathleen Steinhauer, Jenny Margetts, Philomena Ross, and several others.[12]

At the time of IRIW’s founding, Alberta had a plethora of Indigenous rights groups, including the Indian Association of Alberta (IIA), the Métis Association, and Alberta Native Communications Society. But they were all dominated by men, as were federal groups like the National Indian Brotherhood.

Many of these men disapproved of IRIW, calling them “sq**w libbers”[13] and saying that they had made their beds by marrying non-status men and needed to live with the consequences. People crossed the street to avoid them.[14] Many men privately said they supported them and were sympathetic, but publicly criticized them. Philomena Ross’ brother was one of the few men who spoke out on their behalf. For that, his garage was burned down.

But, as Kathleen Steinhauer said, “Nellie wasn’t scared of anybody.”[15] One day Nellie was having lunch with Philomena at the Friendship Centre in Edmonton, and a big man named Ralph Bouvette called out, “Well here comes sq**w lib” to a chorus of laughter from the room. Nellie grabbed him by his necktie, shoved him back against a wall, and gave him a loud scolding in Cree in front of everyone. He was so embarrassed that he didn’t speak to her for years. He eventually got his treaty status back as a result of IRIW’s actions.[16]

The IRIW women faced harassment from outside of Indigenous circles as well. Although it has not yet been confirmed through Freedom of Information requests, Nellie believed that their phones were tapped, their mail intercepted, and they were followed by plainclothes RCMP agents. The RCMP paid informers and infiltrated dozens of Indigenous, women’s liberation, labour rights, and other groups throughout the 1960s and 1970s, so this is not a far-fetched assertion.[17] IRIW members also received death threats, both over the phone and on the street.[18]

Despite these scare tactics, Nellie and her IRIW sisters marched on, pushing the government to repeal Section 12(1)(b) and restore their treaty rights.

They met with then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, who told them, “Why don’t you take up this problem with the chiefs, with the National Indian Brotherhood leadership, and they will listen to you.” To which Nellie responded: “Bullshit, they will!” and got kicked under the table by one of her allies for swearing.

They sat on advisory boards for the patriation of the constitution. They weren’t invited, but delegates from the Native Council of Canada would give up their places at the table – sometimes just passing around nametags so IRIW could be included.[19]

They came close to achieving their goal in 1984 with Bill C-47, which would have brought disinherited Indigenous women and their children back into status. But the Assembly of First Nations and the Native Women’s Association of Canada fought against C-47, instead calling for “‘everybody’ to be reinstated to a ‘general band list,’ and for the bands—chiefs and councils—to decide who would get back onto their band lists.”[20] This would have meant that Indigenous women like Nellie and her IRIW allies would be at the mercy of the band councils, and could have their rights unfairly rejected.[21] Facing this opposition, Bill C-47 died in the Senate on the single vote of Inuit Senator Charlie Watt.[22]

Finally, after almost two decades of organizing, IRIW won. A new government passed Bill C-31 in 1985 – only two months before the sexual equality provisions of the new Charter of Rights and Freedoms came into force.[23] Following Bill C-31, over 160,000 Indigenous people regained their treaty rights.[24]

But the bill was no panacea. Some band governments still resisted reinstating members, and the bill contained a “second-generation cut-off” that terminated Indian status after two successive generations of intermarriage with non-Indigenous people.[25] Following a lawsuit by Sharon McIvor, the Indian Act was amended again in 2010 to address this continued discrimination, but that amendment still left out the descendants of thousands of disinherited status Indian women born before 1951.[26] It was only in August 2019 that the federal government finally amended the Act to include all descendants of women who had lost Indian status dating back to 1869 – which could result in 270,000-450,000 people being able to reclaim their treaty rights.[27] It is important to note, however, that the struggle for recognition – the question of who has status, and who does not, and ultimately, who gets to decide – is ongoing.[28]

What is not in dispute is Nellie Carlson’s legacy, and the role she played to redress the injustice of Section 12(1)(b). Nellie has received accolades for her work, including a Governor General’s Award,[29] a museum exhibit about IRIW at the Royal Alberta Museum,[30] and a school named after her in Edmonton.[31] But she has always been humble about these honours, brushing off praise with her characteristic bluntness:

“Our journey along this trail was not for fame or anything. We were doing it for our children’s rights. That’s it.”[32]

Bruce Cinnamon © 2020

Suggested further reading

Disinherited Generations: Our Struggle to Reclaim Treaty Rights for First Nations Women and their Descendants. Nellie Carlson, Kathleen Steinhauer, and Linda Goyette. University of Alberta Press, 2013.

My Heroes Have Always Been Indians: A Century of Great Indigenous Albertans. Dr. Cora Voyageur. Brush Education Inc., 2018.

Other sources

Nellie Carlson School Profile. Edmonton Public School Board. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://nelliecarlson.epsb.ca/aboutourschool/schoolprofile/

Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie. City of Edmonton. University of Alberta Press, 2004. “Carlson Close,” p. 50

Celebrating 25 Years of the Esquao Awards. Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women, 2020. pp. 8-9. Link: https://iaaw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Esquao-25.pdf

“Bill C-31.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 12 May 2020. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/bill-c-31

[1] Nellie Carlson School Profile. Edmonton Public School Board. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://nelliecarlson.epsb.ca/aboutourschool/schoolprofile/

[2] Disinherited Generations: Our Struggle to Reclaim Treaty Rights for First Nations Women and their Descendants. Nellie Carlson, Kathleen Steinhauer, and Linda Goyette. University of Alberta Press, 2013. p. XXII

[3] Nellie Carlson School Profile. Edmonton Public School Board. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://nelliecarlson.epsb.ca/aboutourschool/schoolprofile/

[4] Disinherited Generations, pp. 28-30

[5] My Heroes Have Always Been Indians: A Century of Great Indigenous Albertans. Dr. Cora Voyageur. Brush Education Inc., 2018. pp. 63-64

[6] Disinherited Generations, pp. XXXII-XXXIII

[7] Disinherited Generations, p. XXI

[8] Disinherited Generations, p. 18

[9] Disinherited Generations, pp. 87-88

[10] Disinherited Generations, p. XIII

[11] Disinherited Generations pp. 39-40

[12] Disinherited Generations, pp. 131-136

[13] Nellie Carlson School Profile. Edmonton Public School Board. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://nelliecarlson.epsb.ca/aboutourschool/schoolprofile/

[14] Disinherited Generations p. 65

[15] Disinherited Generations p. 70

[16] Disinherited Generations p. 70

[17] Disinherited Generations, pp.82-83

[18] Disinherited Generations, p. 93

[19] Disinherited Generations, p. 94

[20] Enough is Enough: Aboriginal Women Speak Out. Janet Silman. Women’s Press, 1987. p. 204

[21] Enough is Enough, p. 204

[22] Disinherited Generations, p. 96

[23] Disinherited Generations, p. XXXIV

[24] Disinherited Generations, p. XXII

[25] Disinherited Generations, pp. 97-98

[26] Disinherited Generations, pp. 98-99

[27] “Indian status could be extended to hundreds of thousands as Bill S-3 provisions come into force.” Jennifer Geens. CBC News, 15 August 2019. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/bill-s-3-indian-act-sex-discrimination-1.5249008

[28] “Some First Nations tighten membership criteria in response to Bill S-3’s extension of Indian status.” Jessica Deer. CBC News, 30 August 2019. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/kahnawake-six-nations-membership-bill-s3-1.5264898

[29] Governor General’s Awards in Commemoration of the Persons Case – 1988 Recipients. Status of Women Canada. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/commemoration/gg/recip-laure/1988-en.html

[30] “Saddle Lake ‘miracle’ women honoured in new museum exhibit.” CBC News, 30 December 2017. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/saddle-lake-indian-rights-royal-alberta-museum-exhibit-1.4449274

[31] “Edmonton school named after Nellie Carlson.” Global News, 30 June 2016. Accessed 8 June 2020. Link: https://globalnews.ca/video/2798238/edmonton-school-named-after-nellie-carlson

[32] Disinherited Generations, p. 113