I want to share my personal history of growing up in one of Edmonton’s Chinatowns in the 1970s. The Chinatown, where I spent my early years of life, no longer exists. All that remains is the Chinese Elderly Mansion seniors’ home just east along 102 Avenue. My Chinatown has now become Canada Place and the Winspear Centre. My childhood house, just east of 102A Avenue, has been long demolished and turned into a brown brick law office and parking lot. My old Chinese school, which was housed in a church basement, no longer teaches Chinese to children, as children no longer live in the area.

The City Farmer’s Market is now an Edmonton Police Services recruiting centre. The former army surplus store is a Greek restaurant. The old GWG factory (that was later turned into the Army and Navy store) is currently the trendy year-round Downtown Farmers’ Market. The Family Pharmacy, which filled many prescriptions for countless elderly Chinese folks, has closed its doors in the past two years. The mah-jong parlours for the various Chinese social clubs have all been shuttered because the old men and women who socialized in them have “passed their bodies,” as we Cantonese speakers say. The first Chinese Gate to welcome visitors has been moved into storage to make way for the incoming LRT. Forty years later, my Chinatown has become a sweet, fond memory of our city; Edmonton is growing on without it.

Born in 1975, I grew up with the last generation of bachelor men. They came from China to build the railroad and start a new life away from famine, war, and the uncertainty of political unrest rolling through China when they were young boys and men. These bachelor men faced racism and poverty and were unable to bring their wives, relatives, families, and children to Canada due to the Chinese Head Tax. The Chinese Head Tax was a restrictive tax, exclusive to Chinese immigrants, meant to keep them from “invading” Canada. It was in place from 1885 to 1923. The very few women who lived in Chinatown at this time either travelled with or joined men who were fortunate to have the money or connections required to bring them to Canada.

By 1975, the men were old, tired and had lost much of their connection to their families in China. Chinatown became their family and home. The old bachelor men had each other, for better and for worse. As one of the few children in the neighbourhood, they treated me preciously. From what I remember as a toddler and from what my mum has told me, I was coddled and loved. Chinese New Year’s meant an abundance of red laisee envelopes and Lucky candies. I remember White Rabbit candies, mini rolls of Haw Flakes sweets, and the coins the older men would give me whenever I went with my mum to buy groceries at the Chinese grocery store on 97 street, or when we went to dim sum at the corner café on Jasper Avenue and 97 Street.

As I learned to speak, I called the elderly men suk suk or gong gong whenever we met them in the café and stores, meaning uncle or grandfather, respectively. The few elderly women were yi yi or po po- auntie or grandmother. I didn’t understand the deeper meaning behind these names when I was a child. At the time, it meant treats, money, and being held by strangers. But my mum understood because the elderly women and men would often reminisce about their families back home. I represented the many children and families that couldn’t be brought to Canada or return to China for reunification. I was a bittersweet reminder of what many of them had back in China but couldn’t have here in Canada.

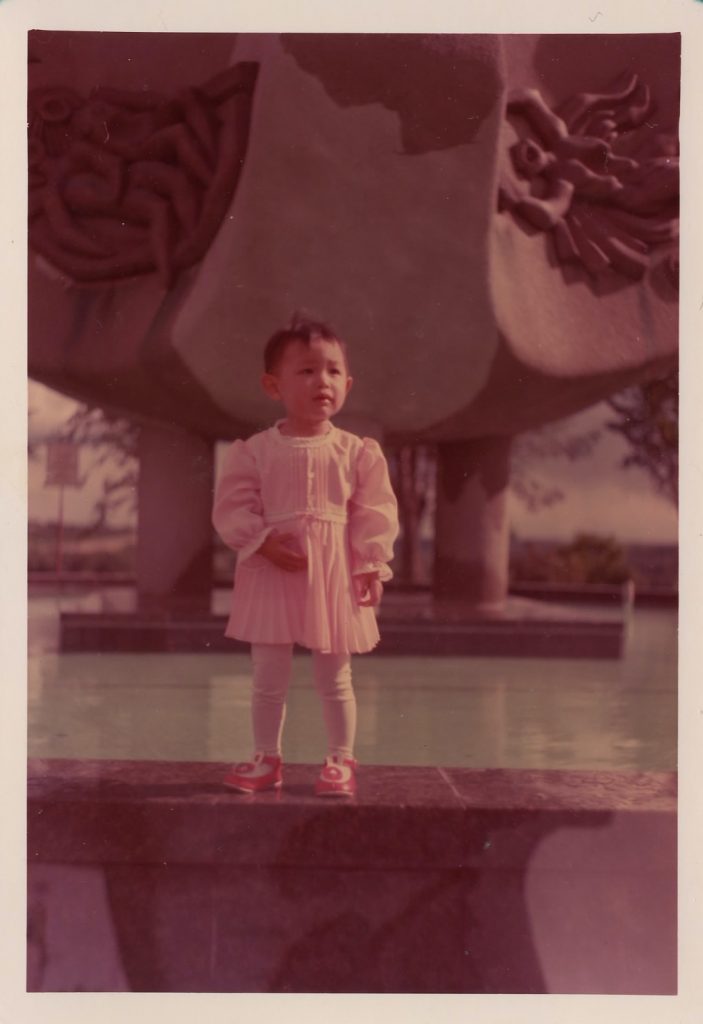

Amy at Government House Park

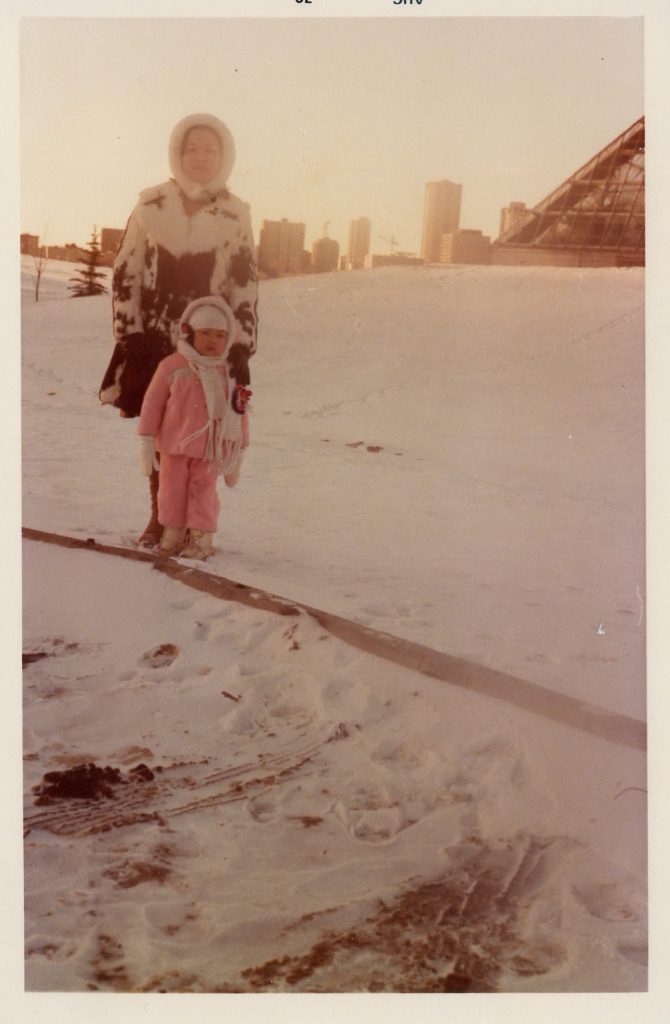

Amy & her mum, Suk Chun Wong, outside the Muttart Conservatory

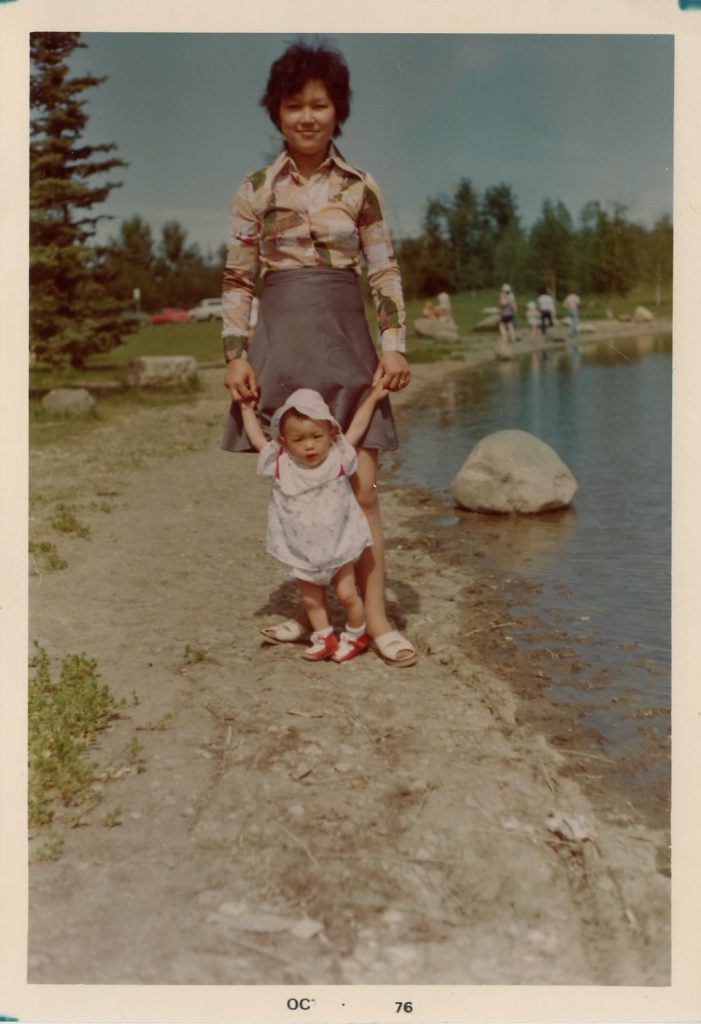

Amy & her mum, Suk Chun Wong, at Hawrelak Park (known then as Mayfair Park).

The families I remember from my Chinatown are the Tses and the Chans. Lo Tse Po Po (old Tse grandma) was the mother. Her son, Tse suk, and Chan suk helped my family adjust to Edmonton and became lifelong friends. I also remember hearing the Taishanese language from the mouths of the elderly. Taishanese was the main Chinese dialect spoken at the time. The first two generations who came to Canada speaking it came from the Taishan district in the province of what was called Guangdong at the time, now called Guangzhou, China. Taishanese is a sister dialect of my mother tongue, Cantonese. My mum (who immigrated to Canada from Hong Kong) had to learn it quickly if she wanted to get around Chinatown and make connections because she only spoke Hong Kong Cantonese and limited English. I learned a strange mishmash of Cantonese (by my mum) and Taishanese by asking for treats from the suks suks and yi yis in the neighbourhood. For me, Taishanese represents another fading and forgotten part of Chinatown. The original Taishanese speakers here in Canada have slowly passed away or are passing away as we speak. And many of the children and the grandchildren of these speakers didn’t pick up the language or have forgotten much it, myself included.

City of Edmonton Archives, ET-28-2210.

I watched Chinatown change with mixed feelings throughout the years, especially whenever I drive along 97 street. I feel sad because this unique part of Edmonton’s history will never be experienced again since the physical structures are gone, as are the people who made those memories with me. But, on the flip side, I feel happy when I go to Lucky 97 or Supermarket 99 and see non-Chinese folks shopping there; I see it as a demonstration of how we as Chinese people have contributed to the broader Canadian identity. We are continuing to make history and memories here in Edmonton and throughout Canada, will continue to do so for many years to come. And I am sure the Tses, Lo po po, and Tse Suk would be so proud because that’s what they would have wanted.

Amy Wong © 2020