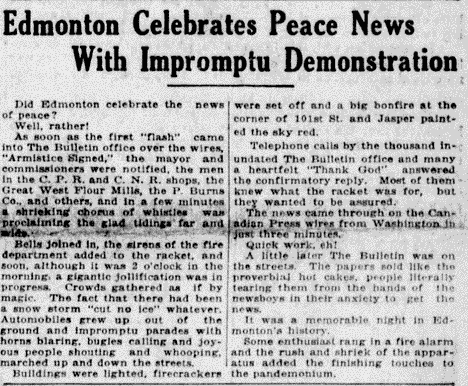

The end of war on November 11, 1918, made headlines in Edmonton’s newspapers: The Morning Bulletin noted: “GERMANY ACCEPTS TERMS”; The Bulletin reported: “EDMONTON CELEBRATES PEACE NEWS WITH IMPROMPTU DEMONSTRATION”; and The Edmonton Journal observed: “SIRENS, BONFIRES AND BIG PARADES NOTIFY THE CITY ARMISTICE IS SIGNED.”

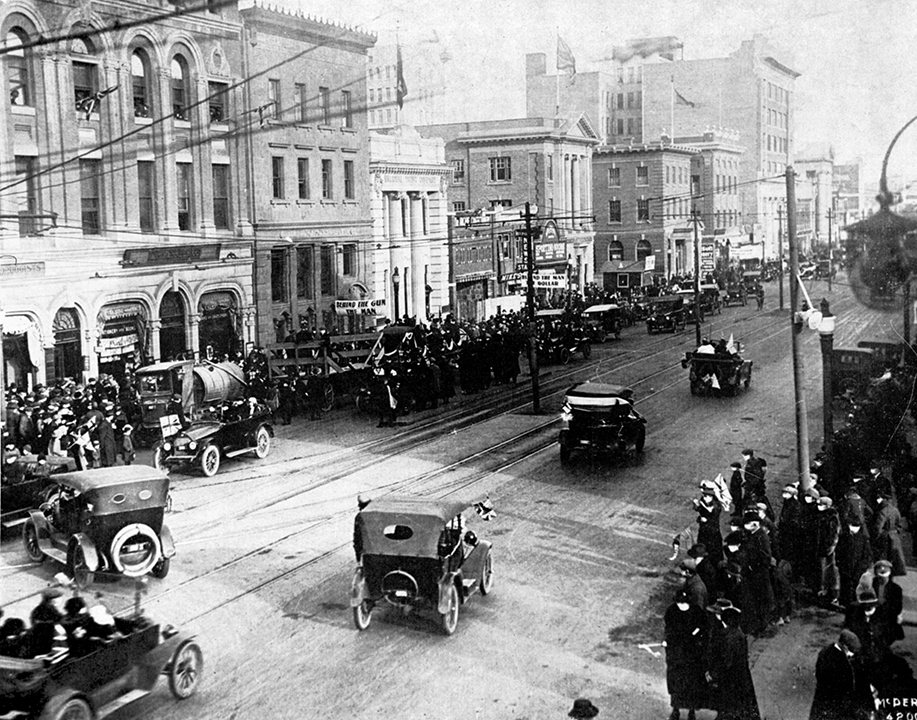

An impromptu parade was organized that made its way down Jasper Avenue. While many turned up to cheer and take part in the exhilaration and festive spirit that the end of the war unleashed, some were kept away by fears of the Spanish Influenza. A few came wearing masks. In a secondary article in the Bulletin, under the headline “MASK ORDER IS LEGAL AND CAN BE RIGIDLY ENFORCED WHERE IT IS BEING OPENLY DISOBEYED,” it was reported that 12 people had died on Saturday, November 9th and 13 people on Sunday, the 10th. At least some were flu deaths. The Spanish flu had struck the city in October 1918 and would remain a threat in 1919 forcing the Province of Alberta to consider quarantine and other measures to check the pandemic. It killed 614 Edmontonians.

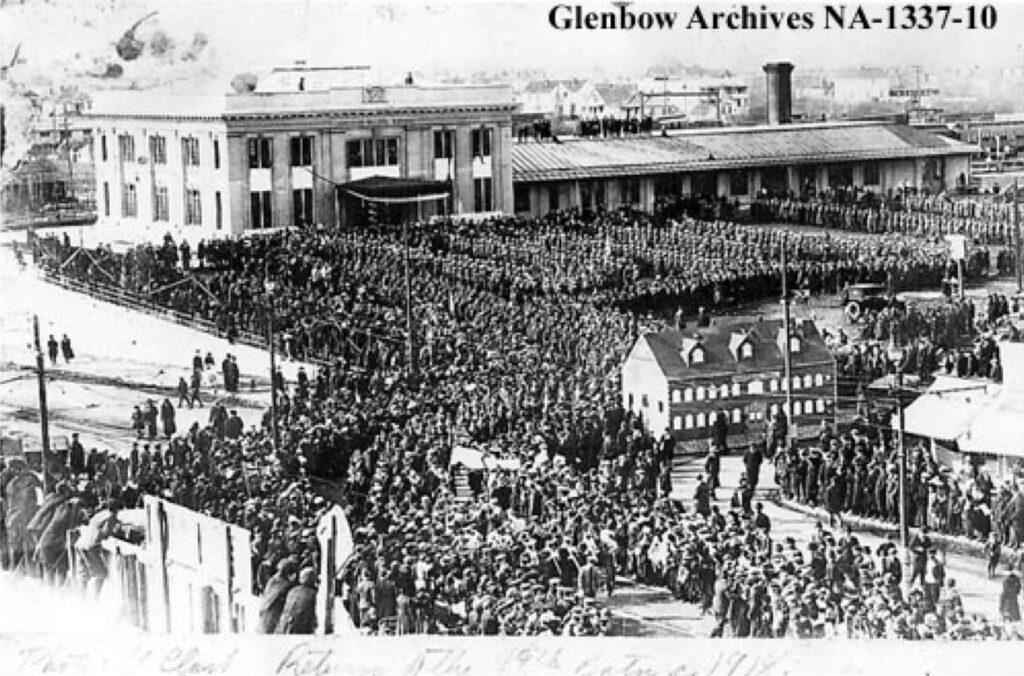

On March 22, 1919, thousands of Edmontonians turned out at the CPR station at 109 Street and Jasper Avenue to see the 49th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, return. This was the Battalion that was most closely identified with the city. The first train crossed the High Level Bridge and was greeted at the station by dignitaries and the Edmonton Journal News Boys’ Band. On the sides of the railway cars, the 49th crest and names of battles were displayed. The men, in formation, marched through the crowds (which totaled about 30,000) along Jasper Avenue to 101 Street and then west to the Armouries.

The men fought in some of the major battles of the war and members won two Victoria Crosses. These included battles fought in the strip of land known as the Ypres Salient in Belgium, which was defended by the British, French, Canadians, and Belgians. Names such as Sanctuary Wood, Mount Sorrel, Passchendaele, the Somme and Vimy Ridge became iconic. Edmontonians, whether serving with the 49th or other battalions fought and gave their lives in all the battles. During the Last Hundred Days of fighting in summer and fall of 1918, they were at Amiens, Arras, Canal du Nord, and Cambrai.

While family and friends rejoiced over those who returned, there were many mourning those who had been lost. Who knows what those who were killed could have achieved.

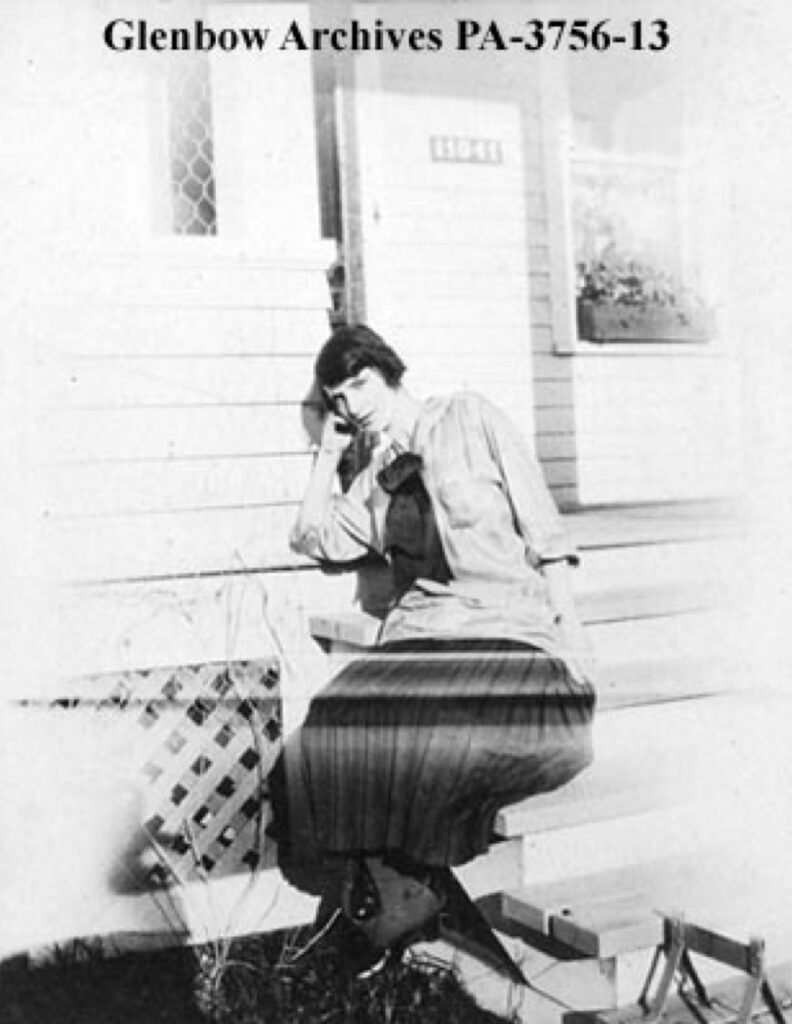

Many young women sent photographs to their sweethearts on the Front. Cassie McKee mailed this photograph to George Lamb, her fiancé, who was reported killed in action in France. She is sitting on the steps of her home at 11541-94 Street, she has written “All Alone” on the reverse of the photo. While women waited for the return of their men on the front, they also raised funds including through the Red Cross and created “comfort packages” with spare socks, sewing kits, handkerchiefs, and cigarettes to send to the soldiers. Other found newly-available jobs in a range of occupations.

The horrors of trench warfare were inconceivable to those who waited. While the homecoming of the wounded occurred throughout the war, wives and families were not prepared to deal with physical injuries including loss of limbs, blindness, long ailments from poison gas, and the nightmares that were part of what was described as shell shock. The sheer numbers of cases overwhelmed stressed medical agencies and institutions and families were mostly left to cope without support.

The first memorial to Alberta’s war-time dead was unveiled in Beverly, which began as a small mining community on the outskirts of Edmonton. The Cenotaph is located at the southwest corner of 118 Avenue and 40 Street. On October 17, 1920, Lieutenant Governor Robert G. Brett officiated with local Beverly veterans and families in attendance. Other special guests were Brigadier-General William Griesbach, Edmonton Mayor Joe Clarke, and Beverly Mayor Fred Humberstone, the owner of the mine of the same name that had provided employment to many of the town’s men. Of the town’s total population of about 1,000, 170 men enlisted and 27 were killed.

By Adriana A. Davies, CM, Cav. d’Italia, PhD