In the middle of the twentieth century, G. S. Woodward was one of a handful of Edmontonians who plied the trade of salvage man at the city’s largest post-war landfill, Beverly Dump. If you’ve ever played disc golf, paddled around a pond, or enjoyed a round of mini-golf at Rundle Park, surprise! You have spent your leisure time on top of one of Edmonton’s most notorious dump sites.

But let us return to Mr. Woodward. During the Great Depression and World War II, men like Woodward did brisk business sorting through metals, car parts, and furniture dropped off at city dumps. At a time when the word “recycle” did not exist in the popular vocabulary, Woodward repaired and repurposed old parts and sold them back to consumers.

As the Beverly Dump expanded during the boom in post-war consumer culture, Woodward was desperate to hang on to an informal arrangement with the City. It was an arrangement in which salvage men paid a certain sum to the City for rights to sort through garbage and then resell certain items. Think of salvage men as mobile thrift shops. The catch was that the City was also supposed to get a fifty percent cut of what was sold back from the dump.

Woodward wrote the City Manager in 1958, asking for a better deal in a shaky handwritten letter. Even in the best of times, salvaging, according to Woodward, was a “a risky proposition. You can lose your shirt sometimes, other times, you make money.” As if the financial woes weren’t enough, Woodward had to contend with black bears also hungry to rummage around the landfill.

Edmonton had an ad-hoc relationship with its garbage until this point in history. Dumps and shantytowns had appeared in ravines and along the River Valley (see World Class Dump #1). An ambitious attempt to burn all the garbage backfired when the city’s incinerator created a blizzard of black snow one winter (see World Class Dump #2). The City Engineer desperately wanted to modernize its trash collection so that citizens could trust that their trash would be out of sight, out of mind and, most importantly, out of smell, for good.

Post-war North American culture witnessed a paradigm shift in how people thought about their refuse. Only a few decades before, the reuse and repurposing of old items was deemed necessary and virtuous. Ads during World War II urged citizens to not waste anything. People were urged to save old car tires, feed slops to hogs, plant victory gardens. As the North American economy surged in the 1950s, consumption replaced conservation as a virtue of Western capitalism in its fight against communism. Conspicuous consumption led to massive amounts of garbage, and rapidly growing cities like Edmonton had nowhere to put all the trash.

As I discussed in the previous instalments of World Class Dump, Edmontonians were accustomed to having their incinerators and landfills right in the middle of the city. We had an up-close and personal relationship with our garbage, tossing refuse down the slopes of the River Valley or burning tons of garbage every day near the present site of the Muttart Conservatory. But incineration and urban landfills were both noxious and dangerous.

All of this meant that men like G. S. Woodward became a sort of nuisance. When salvage men didn’t pay the City its share, the Engineer sent angry letters, severing their contracts and demanding restitution. Woodward was told to submit a formal bid to salvage from the Beverly Dump. He turned in a long rant that ranged from the vagaries of his occupation to speculations on local murder mysteries. His formal bid—such that it was—was rejected due to its lack of conformity with regulations.

Had Woodward been born in the latter 20th century, he might have found a niche for himself as an artisan curating and restoring trash to treasure. I like to imagine him at the Old Strathcona Famers’ Market or the Royal Bison, selling buffed up chrome pieces of old cars turned into lamps or coffee tables. But he was born too early for our hand-curated, recycled age.

****

Before we turn to the transformation of the Beverly Dump into Rundle Park, we need to look back at a curious chapter in Alberta’s history, when coal was king. Just east of Edmonton, the little hamlet of Beverly staked its claim on coal mining at the turn of the 20th century. Mines known as “gopher holes” burrowed into the side of the North Saskatchewan River valley as immigrants from Europe scratched out an existence as miners.

The holes went deeper and deeper into the land, extending for miles, even as profit margins became thinner and thinner in the 1920s, as the world was turning to oil and natural gas.

Many of the mines were unregulated. Buildings constructed on top of mines collapsed. As Edmonton’s population soared, Beverly’s actually shrank. The town continued mining, even as the village became saddled with debt. By the 1950s, its main attraction (except for Alberta’s first cenotaph) was its burgeoning dumpsite.

The Beverly landfill was bought by the City of Edmonton in 1956 for just under $30,000. The site, just south of the Village of Beverly, had been a farm of the Prins family, who had immigrated from Holland. The Prinses had tried their hand at coal mining, but never found much profit in it. Their acreage was mostly countryside, and the land included a ravine fifty feet wide and half mile long. Underneath the farm were serpentine coal mines, many unmapped and in dangerous states of repair. The farm also had an open sewage lagoon.

Meanwhile, Rundle Heights subdivision was encroaching on the site, but the City Engineer saw the dump as a temporary solution to a growing problem. The engineer estimated that the Beverly dump site would reach maximum capacity within ten to fifteen years from the time Edmonton started dumping there in 1958. In 1961, Beverly voted to amalgamate with Edmonton.

As the new Beverly Heights subdivision grew, the Dump became a contentious issue. Suburbanites didn’t take kindly to the noxious smells, salvage men, and roaming black bears. They wanted it closed for good. One Edmonton Journal writer claimed that the dump site was the issue that elected Mayor Ivor Dent in 1968. It was Dent who helped steer one of the most dramatic make-overs the City has ever witnessed.

What began as a call for civic renewal on the dumpsite quickly turned into a massive park development project. The Beverly Dump would not only be shut down, it would be turned into a 319 acre park to “rival Copenhagen’s famed Tivoli area.” [1] The site was to be re-baptized as Rundle Park, named after the Methodist missionary who had a rather miserable spell in Western Canada in the middle of the 19th century.

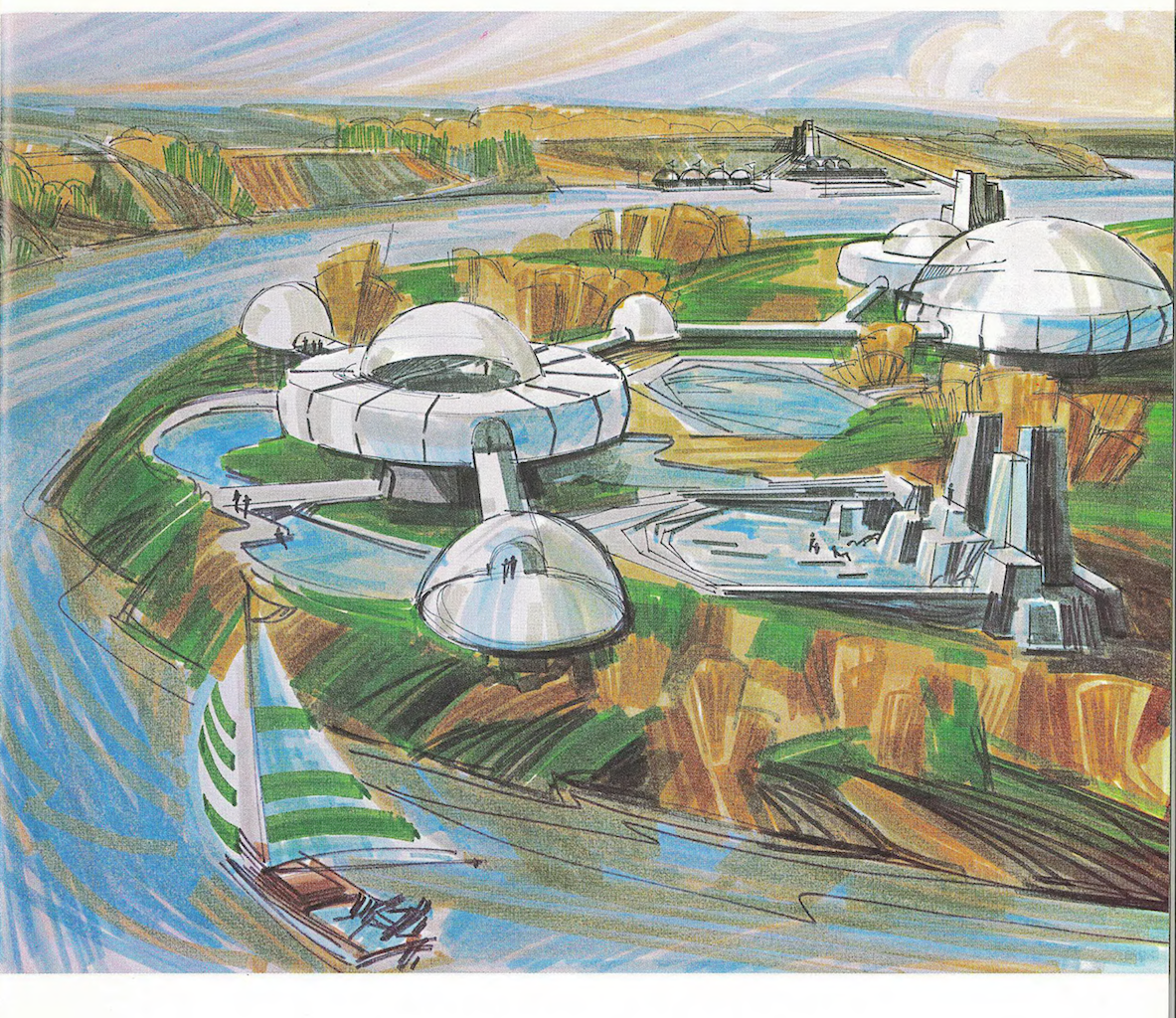

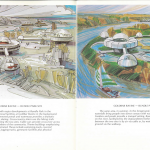

Rundle Park, unlike its dyspeptic namesake, was to be a thoroughly modern and happy place. An early proposal sported a futuristic weir with Blade Runner-esque pods connecting the north side of the river with a park across the river in Gold Bar. The early sketches looked like something out of a disco-era utopia.

What resulted was a common Edmonton narrative: wild dreams tempered by a high price tag and an end product that didn’t quite match expectations. The plans for the weir connecting Rundle and Gold Bar were abandoned by 1975, but the plans to make Rundle Park a world-class park survived, albeit in a more modest version.

These plans included an “extensive playground with educational opportunities such as a maze, a village to be built by children, rides, an illusion house, a climbing mountain, a theatre and build-your-own-environment with creative structures.” [2] Sports facilities would include swimming pool, a lagoon system for boating, a cable-car ride to another park across the river, par three golf course, tennis courts, and soccer field.[3] In sum, Rundle would “develop into such an attraction that Edmontonians would come from all over the city to it.”

For a while, the world-class park on top of the world-class dump did attract people from all over the city to enjoy its amenities. It was a destination for birthday parties, family outings, and bored teenagers. But signs of the old dump reappeared, almost like ghosts. In the 1980s, a resident of Beverly Heights noticed that dozens of old automobile tires had surfaced near the park after some torrential rains. Some residents feared that their water was contaminated and City officials had to reassure them that the dump was contained for eternity.

By 2007, Paula Simons wrote that some of the magic of Rundle Park had worn off. It was looking tired and defeated. The roads were a nightmare and many of the facilities had not been upgraded from their disco-era origins. To the throngs of families picnicking, canoeing, and minigolfing in the summer, though, the park is still one of Edmonton’s treasures, if it is built on garbage.

Sources:

[1] DeMarino, Guy. “City may build northeast park.” Edmonton Journal. Jan 28, 1969

[2] “A Provincial Proposal for River Valley Development for Metropolitan Edmonton” by Environmental Planning Division, Alberta Environment. April 1974

[3] Ibid.