Horses were a vital resource at Fort Edmonton and hundreds were kept by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in the nineteenth century. Horses hauled cargo, allowed employees to travel far for the hunt, and broke the land for food crops grown near the trading posts. The company fiercely defended its horses against thieves, which resulted in one of the most violent incidents in the fort’s history: a dramatic hand-to-hand duel in a river followed by pitched battle outside of the palisade walls.

Despite the popular image of First Nations hunters on horseback, galloping across the plains at high speed after a charging buffalo, plains horse culture was short lived and a relatively recent development. Since time out of mind, plains peoples had been pedestrian cultures. The horse was a late arrival and was European in origin. Horses and the knowledge of horse riding had been traded up between nations from what is now California after the first few were sold by or stolen from Spanish colonialists there. The horse grew in importance on the plains incredibly rapidly. They allowed First Nations groups to vastly expand their travelling range. As beasts of burden, horses could help First Nations carry more supplies further. The horse changed bison hunting techniques; instead of whole community affairs, skilled riders on horseback could kill choice animals. Horses also increased the pace of war.

The first horses arrived in what is now Central Alberta in the 1730s-1750s from the south; the Blackfoot received them in trade from the Shoshone. When European fur traders first arrived in the Edmonton area and set up shop at Fort Augustus and Fort Edmonton in 1795, horse culture was at its height. So was the cultural importance of horse theft. Stealing horses was a way to demonstrate one’s skill as a warrior and as a leader.

Horses were a source of prestige for all people living in the west. Fort Edmonton’s Chief Factor John Rowand owned a large herd of horses, received as a dowry when he married his wife Louise Umphreville, and it is said that his wealth in horses afforded him the respect of the Cree. Rowand heartily enjoy horse racing, and in 1825 he had a race track built around Fort Edmonton. The hundreds of horses owned by the company and by its employees were kept in a stockade near the fort and also pastured at the region known as Horse Hill in what is now northeastern Edmonton.

Horse theft was endemic in the West during the early nineteenth century. The first recorded instance in Edmonton was in 1799, in which 20 horses were stolen and two were killed. The Edmonton House Journals of 1806-1821 and the correspondence of company employees are peppered with reports of horses stolen by “Stone Indians” and others who made off with these valuable animals. To combat these thefts, the Hudson’s Bay Company employed horsekeepers who took their job very seriously.

François Lucier (or Lucie, or Lussier, depending on who was writing) was one such horse guard. Born in 1796 of Cree and French descent, he worked for his entire career in the Saskatchewan District, and for over twenty years as a horsekeeper. He was notorious for one infamous incident in 1826 in which he dramatically chased down and grappled with a horse thief. As described by none other than HBC Governor Sir George Simpson:

“. . . a band of Assiniboines had carried off twenty-four horses from Edmonton; and, being pursued, they were overtaken at the small river Boutbière. One of the keepers of the animals, a very courageous man, of the name of François Lucie, plunged into the stream, grappling in the midst with a tall savage; and in spite of his inferiority of strength, he kept so close that his enemy could not draw his bow. Still, however, the Indian continued to strike his assailant on the head with the weapon in question, and thereby knocked him off his horse into the water. Springing immediately to his feet Lucie was about to smite the Assiniboine with his dagger, when the savage arrested his arm by seizing a whip which was hanging to his wrist by a loop, and then turning round the handle with a scornful laugh, he drew the string so tight as to render the poor man’s hand nearly powerless. François continued, nevertheless, to saw away at the fellow’s fingers with his dagger till he had nearly cut them off; and when at length the Assiniboine of necessity relaxed his grasp, François, with the quickness of thought, sheathed the deadly weapon in his heart.”

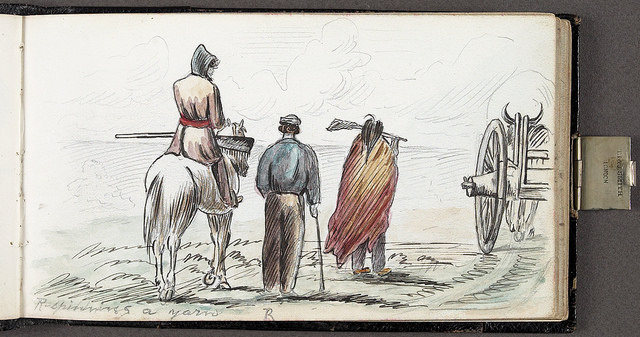

The story of Lucier’s impressive feat was clearly told and retold, not infrequently by Lucier himself, who continued to work as a horsekeeper for the HBC until 1852. The travelling artist Paul Kane repeated the dramatic story in his own account of his travels in the West twenty years after the fight took place. Kane went buffalo hunting with Lucier in the 1840s and Kane clearly found Lucier to be an intriguing figure, painting his portrait. Kane claimed that Lucier recounted the story to him almost exactly as Simpson related in his work – it was clearly a tale worth repeating! Kane said that Lucier elaborated with further gruesome details: the horse thief did not die straightaway, though Lucier “had ripped his breast so open that he could see his heart throbbing, and that he never let go the lasso of the stolen horses until it ceased, which was for some minutes, though he tried to pull it from his hand.” The story of his battle with a horse thief was not one that Lucier would let die even two decades later.

Despite the ferocity of horse guards like Lucier, horse thieves were not deterred. The day after Lucier fought and killed the horse thief in the river, a group of thirty Nakoda (“Stoneys”) sought to steal all of the horses kept in the compound near the Fort while most of the horse guard were at Horse Hill. A battle ensued in which four company men (two Cree, two HBC employees) were injured and six Nakoda were killed.

Rowand wrote of how unusually violent this thwarted theft had been: “This is the first instance known in this department of so many Indians being killed by the whites. Self preservation is our first law naturally to everyone. . . . The Company’s affairs at this place cannot be carried on without horses and to protect them most other concerns are subservient but to allow them to be passively taken from us is to abandon the interests of the company and to render ourselves tools for the Sport of the Indian[s]. . .”

On the one hand, trade at Fort Edmonton depended upon good relations with the Indigenous peoples of the West. On the other hand, the cultural importance of horse theft as a way to demonstrate one’s skill and leadership was incompatible with the way that the HBC was run. The result was battle just outside of the stockade walls.

Lauren Markewicz © 2016

Bibliography

Binnema, Ted, and Gerhard Ens, eds. The Hudson’s Bay Company Edmonton House Journals, Correspondence & Reports: 1806 -1821. Calgary: Historical Society of Alberta, 2012.

Binnema, Theodore. Common and Contested Ground: A Human and Environmental History of the Northwestern Plains. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

Brink, Jack. Imagining Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump: Aboriginal Buffalo Hunting on the Northern Plains. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2005.

Kane, Paul. Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts, 1859.

McClung, J.W. Law West of the Bay. Edmonton: J.W. McClung, 1997.

Simpson, George. An Overland Journey Round the World During the Years 1841 and 1842. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847.