Edmonton’s history is full of remarkable women. From Beatrice Carmichael to Thelma Chalifoux, from Betty Stanhope-Cole to Felicia Graham, from Gladys Reeves to Decima Robinson, hard-working Edmonton women have been contributing to our city for centuries with little recognition compared to their male counterparts. One person who’s earned her place in the pantheon of great Edmonton women is Eda Owen.

In an era where women were not considered persons under the law—let alone considered qualified to be working as scientific professionals—Eda Owen was named as the Provincial Agent and Weather Observer for Alberta. From her home in the Highlands, the England-born settler spent 28 years meticulously recording weather conditions in Edmonton and faithfully compiling reports from other stations across Northern Alberta and the Northwest Territories. She sent these reports to the Headquarters of the Dominion Meteorological Society in Toronto every day, and her data was invaluable to aviators, farmers, forest rangers, and journalists across Canada and the United States.

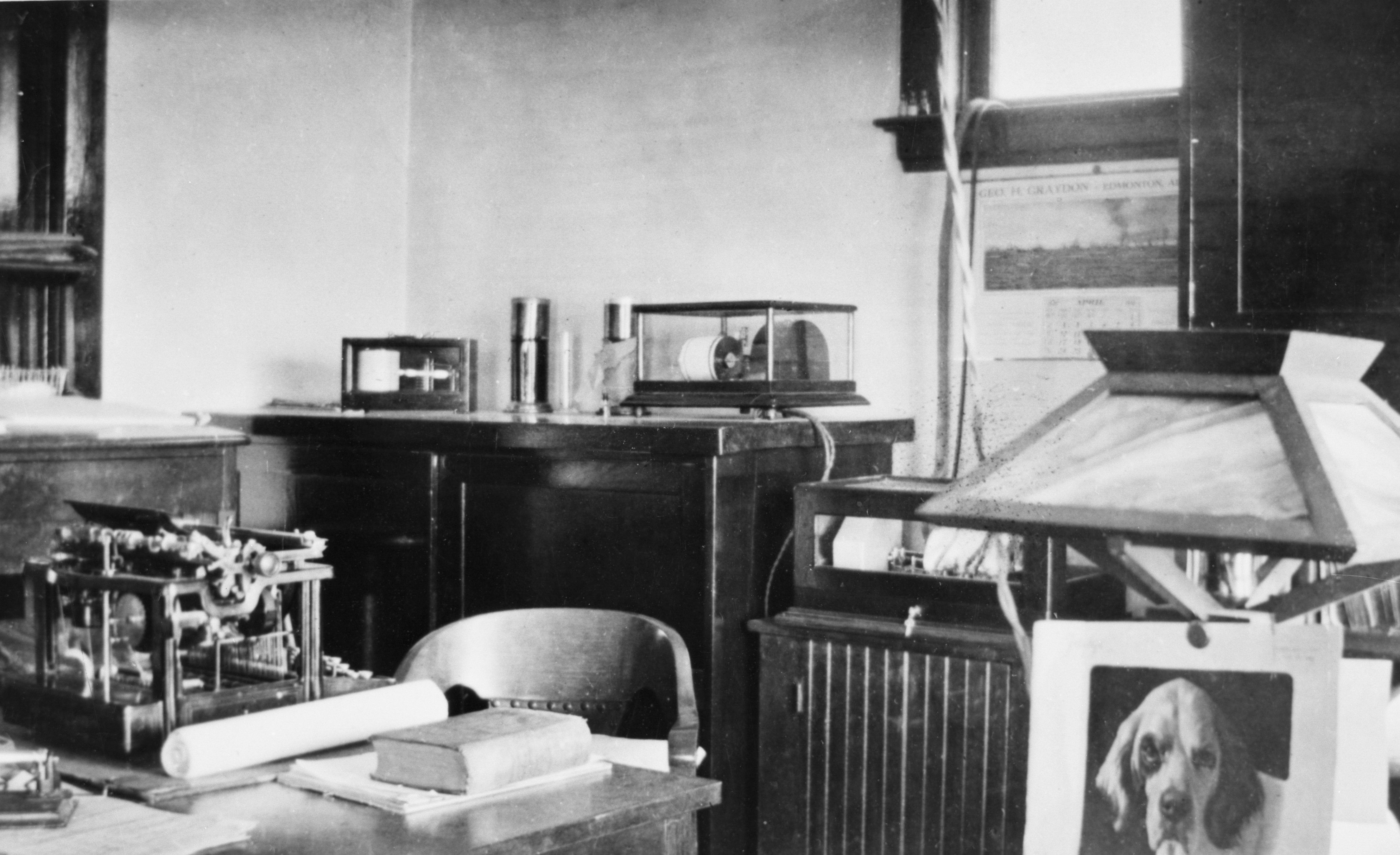

“Her work was incredibly demanding,” notes the Alberta Register of Historic Places, which designated Eda Owen’s home office/meteorological station as a historic resource in 1994. “The Highlands station was arguably the most significant meteorological post outside of Toronto. Eda was required to take hourly readings from 36 different instruments throughout the day and compile reports from over 140 stations in the region.”

Eda woke up at 5:30AM every morning, read her instruments before getting dressed, and phoned in the information to the telegraph office to pass along to Toronto. Completely devoted to her work, the phone was ringing off the wall day and night with calls from reporters and curious citizens asking about the weather.

“Although forecasts were never encouraged by headquarters, Eda couldn’t resist giving one if someone asked her,” writes her granddaughter Phyllis Patterson. “She loved to demonstrate her knowledge and experience. Usually she was often more accurate than headquarters because she was in Edmonton, and headquarters were in Toronto. Forecasters in Toronto did not know how unstable the weather was in Alberta in comparison with Ontario. Eda did. The weather came alive in Eda’s face. She loved her job. She lived, ate, and slept her job.”

When she first arrived in Edmonton in 1908, Eda Owen knew practically nothing about meteorology. A child of Liverpool and London, Eda came from a wealthy family and all that was expected of her was that she should make a good marriage. Unfortunately, a childhood accident damaged her eyes and made it necessary for her to wear glasses—a feature that her parents were sure would drive away any potential suitors and doom Eda to spinsterhood. Thankfully, Captain Herbert Owen, an officer in Her Majesty’s navy, was willing to overlook this terrible flaw.

Following Herbert’s brother, the Owens moved to Canada and eventually wound up in Edmonton, where the retired sea-captain found work as an assistant meteorologist and his wife adjusted to the unexpectedly harsh prairie climate. Always curious about her husband’s work, both at sea and now on land, Eda learned how to collect and interpret meteorological data from Herbert and assisted him in his duties.

In 1915, as the Great War increased in pitch, both Herbert and his boss, chief meteorologist Stuart Holmden, enlisted in the Canadian armed forces and travelled to Europe. Eda stepped in as her husband’s place-filler, vowing she would warm his seat until he returned. He died in a German prisoner of war camp in 1917.

Herbert’s death destroyed Eda, and put more strain on her already frayed relationship with their only child Kate. Never one for close friends or confidantes, Eda dealt with her grief by throwing herself into her work. For six years, Eda continued to chart meteorological data and submit reports to Toronto, all the while still under the title of assistant meteorologist.

In 1921, the Department of Marine and Fisheries officially appointed her as Provincial Agent. Eda became the only woman in Canada to hold such a position, earning a living wage and residing in her Highlands weather station home at a time when many returning servicemen were unemployed and homeless.

For the next 22 years, Eda continued the daily grind of her labour-intensive and time-consuming work. But in addition to checking her instruments (which included terrestrial radiators, hydrometers, maximum and minimum thermometers, self-recording rain and snow gauges, anemometers, thermographs and a solar thermometer) dozens of times every day, she also had some extraordinary experiences as her reputation grew.

Eda testified for the defence in a manslaughter trial and helped get a man acquitted after he accidentally struck a pedestrian with his car on a snowy night. She liaised with the US Army during the war. She faithfully documented the spring break up every year and eventually began to predict the day when the river would be freed from its ice chrysalis. She helped a team of British meteorologists who went north on an Arctic expedition to study the Aurora Borealis. And after her daughter’s marriage disintegrated, she legally adopted her granddaughters and raised them as her own children.

By the late 1920s, Eda had become locally celebrated and nationally known as the “Weather Woman of Alberta,” with profiles in Maclean’s, the Toronto Star, a Fox newsreel broadcast, and the Christian Science Monitor. Having previously been seen as an esoteric concern for just the navy, meteorology was slowly gaining recognition as an important and socially valuable science. Eda’s tireless work played no small part in the growth of Canadian meteorology, and she did her best to make sure that everyone could benefit from her knowledge–be they academics, bush pilots, or average citizens.

Today, Eda Owen’s house at 11227 63 Street looks much the same as any of the other historic homes in the Highlands (like the nearby Marshall McLuhan childhood home). But when Eda lived there, the house stood out. A 60-foot tall wooden tower, painted bright red, was perched atop the roof, holding a rotating anemometer to gauge wind speed.

“This meteorological sentinel, painted red, was a local landmark in the Highlands neighbourhood for decades before its removal,” notes the Historic Places Register.

Eda climbed the tower every day. In spite of family turmoil, devastating personal loss, and widespread misogyny, she stuck to her routines and devoted her life to science.

“Always stimulating, rarely cuddly, Eda was tough with the girls, but she was warm,” writes her granddaughter. “She became a feminist (largely through circumstances). She worked without intending to and lived in two worlds, a man’s world, science, and a woman’s world, where social life and status were important for survival. She had to cope with prejudice against women who worked. She raised her grandchildren. She never received the pay or the recognition a man would have received. While Eda did not invent or change anything in the world of meteorology, she sustained her office and kept it in an orderly fashion, during a time when meteorology struggled for existence in Canada.”

SOURCES:

Edmonton Historical District Walking and Driving Tour: The Highlands, The Highlands Historical Foundation/Alberta Community Development. Dorothy Field, Monika Dankova, Judy Armstrong. 1993.

Eda the Weatherlady. Phyllis M. Patterson. Calgary, Kindred Spirits: 1994.

Eda the Weatherlady’s house, YEGisHome.ca. Real Estate Weekly. 22 May 2008.

Alberta Register of Historic Places. Heritage Resources Management Information System. Alberta Culture. 2013.

Alberta Heritage Survey Program. Heritage Resources Management Information System. Alberta Culture. 2013.

Bruce Cinnamon © 2016