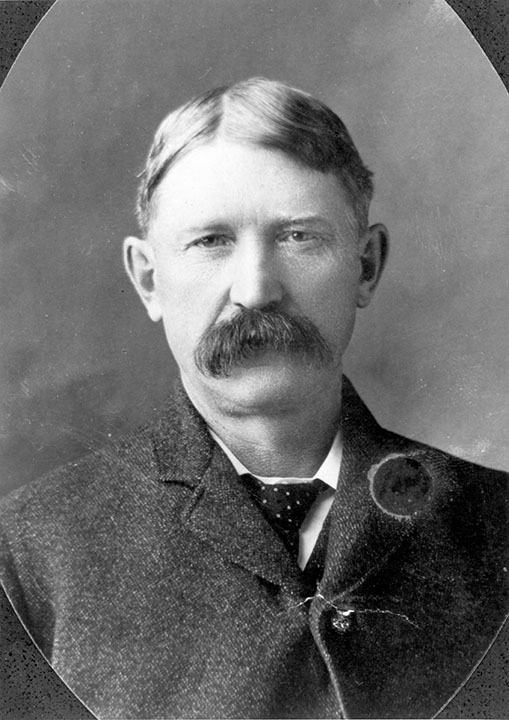

When history is told, it largely reflects events, understandings and individuals who best serve the desires of the recorder. In terms of Amiskwacîwaskahîkan and other locations throughout the West, this history is misrepresentative of individuals and their true motives or undertakings. In the case of Richard Henry Secord, known in common circles as Dick, the process of shining new light on history applies to his dealings with Indigenous peoples in the North West Territories. Arriving in Edmonton from Brant, Ontario in 1881, Secord would go on to play a devastating role for Métis people looking to settle in the west. Gaining support in late 1870s, the government would begin implementing a policy that would forever change the way land was dealt and owned throughout Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Upon continuation of a teaching career in the blossoming Edmonton Public School System, Secord would soon venture into the thriving fur trade business. Partnering in 1883 with another teacher, John Alexander McDougall. The two later established themselves as purveyors of furs, mercantile and land holdings. At this time, Fort Edmonton and the settlement was experiencing continued growth in population from settlers seeking prosperity. The two would continue to do business as traders for some time, until the landscape of the North West Territories shifted with Canada beginning fulsome implementation of the obligations outlined in the Manitoba Act of 1870.

Prior to 1870, continued disagreement and colonial pressure to adhere to Crown policy created a sense of turmoil in the Red River area. When leaders like Riel and Dumont came forward to establish a new land for their people, the developing government of Canada was willing to negotiate in order to avoid continued unrest. Through the provisions of the Manitoba Act, 1.4 million acres was to be set-aside for future Métis generations. Implementation of this granting system was ad hoc in the beginning, however with changes to the Dominion Lands Act in 1879, a commission was established to ensure the work was carried out. It was through the actions of this commission that individuals like Secord found, and exploited, a mechanism for immense personal gain.

As the commissions began to venture west, they would stop in locations of interest to process claims. The claims process would become one of the most flawed and corrupt of policies directed towards Indigenous peoples. Tales of claims commissioners establishing offices next to speculators and land swindlers with copious amounts of alcohol on hand to help expedite dealings would abound. Through the claims process, Métis descendants would be provided a certificate, authenticating their tie to the Manitoba Act and Red River. These certificates ranged from 160 acres/dollars or 240 acres/dollars. Once a certificate was attained, Métis would then redeem that certificate for surveyed lands. In tandem, land speculators, with support of the government, were able to establish a lucrative industry.

To the detriment of the Métis, who at the time did not fully comprehend the foreign system, traders like McDougall and Secord began to venture away from mercantilism. Through continued exploitation of the Crown system, McDougall and Secord were able to become “Edmonton’s First Millionaire Teachers”. The Scrip system allowed those with resources to purchase a certificate for face value or perhaps a marginal increase, then redeem the certificate on behalf, sometimes through fraud, of the original holder and re-sell for profit. Once a sale was undertaken, unbeknownst to Métis, their claims and rights would be extinguished in the eyes of the Crown. One such example of this flawed process dealt with Marie Rose Mageau, and a legal case that was to be heard at the Supreme Court of Alberta.

On November 3, 1900, Ms. Mageau’s mother received her Scrip certificate allocating 240 acres/dollars. According to court documents, it was alleged that McDougall and Secord had purchased Ms. Mageau’s Scrip Certificate Number 2298 in 1902 for the sum of $480.00. Ms. Mageau, illiterate and unaware of the Scrip process, stated the initial transaction took place without her consent or knowledge. Court documents allege that Secord paid numerous visits to Ms. Mageau and her family to attain a full release through intimidation and coercion. Secord achieved said release after paying an additional $500.00, which Ms. Mageau attempted to return after learning of the ramifications. This circumstance becomes even more troublesome when the land in question was worth an estimated $5,000.00.

In their defense, McDougall and Secord acknowledged all the claims around the initial sale, redemption and subsequent payment for release. However, they did not admit to the claims of intimidation and coercion. Counsel would state that Ms. Mageau knowingly sold the certificate to Secord in 1901 at the age of 18 years, and even if the transfer were not done willingly or with full cooperation, the issue of cancellation would have to be elevated to federal authorities for proper adjudication. Slated to appear before the Supreme Court for judgment on February 28, 1911, the case was dismissed and it remains unclear as to whether there was a settlement reached. In isolation this case seems irrelevant, however in 1921 Secord would once again find himself in legal trouble regarding Métis Scrip.

A stipulation of the Scrip system was the requirement for certificate recipients to be present at a Dominion Lands office when redemption of the certificate took place. In this regard, it became common practice for business conducted away from lands offices to be expedited by the process of impersonation. In these instances, speculators would hire a Métis imposter to pose as certificate holders, sign over ownership and receive a small payment for their role. In 1921, Flora Taylor brought a claim of impersonation forward in reference to dealings with Dick Secord. Before said case would be brought to trial, Ottawa amended the criminal code with specifics to the Scrip system and instituted a statute of limitations regarding claims of fraud. Once this amendment took place, the charges were dropped against Secord. The history around these claims, like many other areas of Indigenous history and wrongdoings, would fade behind the dominant narrative of prominent Edmontonians.

Dr. Frank Tough, Presentation to the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, October 23, 2012: https://provincialarchives.alberta.ca/static/interesting-cases/civil-meunier-mcdougall-secord.html

Rob Houle © 2016