Rising out of the Rocky Mountain glaciers, flowing ever eastward toward Hudson Bay, the North Saskatchewan River has meandered across the continent for at least 12,000 years. As with most massive watercourses, it has existed in a state of continuous physical change; conditions are sometimes gentle, a languid and unhurried flow toward the sea, other times the current is chaotic and turbulent. Depending heavily on larger environmental factors, each season in the lifecycle of the river brings forth events which can vastly alter both the streambed and the very existence of people nearby. Marked in our most recent memory is the flood of 1915 that devastated Walterdale, Ross Flats (Rossdale) and eastward to Gallagher and Fraser Flats. This, seemingly, sudden and unpredictable aqueous assault levelled homes and destroyed businesses, leaving over 2,000 people homeless.

Truth be known, this catastrophic event was only one of many; floods of some magnitude occurred in 1825, in 1830 and, again, in 1899. Had the inhabitants been able to garner a longer-term, broader understanding of the nature and behavior of this shifting waterway, they may have been able to mitigate the effects of the flooding. It would seem, that the collective memory of the citizenry had been muddied by the excitement of expansion; their pioneering spirit ever eager to look forward, to put down roots, had failed to look back and adjust their dreams to fit nature’s reality.

Indigenous Peoples have lived, and thrived, on the lands surrounding Amiskwaskahegan (‘Beaver Hills House’ in the Cree language) since before time mattered or was measured. For millennia upon millennia, the kisiskāciwani-sīpiy (‘Swift Flowing River’ in the Cree language) served as both highway and border; as territorial control waxed and waned through time, the Dene of the north, the Nehiyawak of the woodlands and plains, the Nakoda of the foothills to the west and the Tsuu T’ina and Niitsitapi of the south have travelled these lands. Generations before European contact, Indigenous people retraced ancient food gathering trails in search of berries, nuts, mushrooms and root vegetables. From season to season, whole communities tracked large game animals such as bison, deer, elk and moose, living closely with the land, sustaining their families with all the earth had to offer.

The original peoples of this landscape hold an intimate knowledge deep within their cultural memory, a way of knowing that Western science has labelled as ‘Ethnoecology’. The capacity, generation upon generation, to transmit sophisticated and multi-layered levels of environmental knowledge; information about weather patterns, seasonal climatic conditions, ecology and geology were vital. Something as complex as flood prediction developed out of an essential need to survive, to know how to navigate through the land. Knowing where to camp for the season was indispensable.

Archaeologists have found indications of permanent camps throughout the river valley; some larger, formed when many people camped together or a group of people used the site over and over for thousands of years, other camps were smaller, likely used as temporary settlements while seeking out resources such as stone for tools, berries, fish or animals. There are nearly 800 occupation and quarry sites in the Edmonton region. The multitude of both permanent and interim sites have put into question antiquated anthropological assumptions about the nature of Indigenous life ways and procurement systems. It is now known that Hunter-Gatherer societies of the plains were not at the mercy of nature but, instead, maintained a relationship with the land that ensured their cultures flourished to this day.

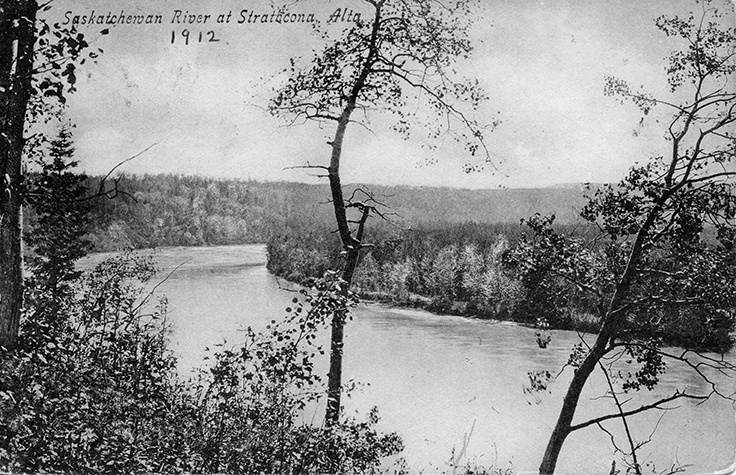

The elevated banks offered sentries a wide view of the sprawling landscape, a sweeping perspective to assess one’s place in the vastness of the prairie. Hilly vistas scattered along the riverbank were ideal places to camp, some of the largest and longest occupied archaeological sites are situated near the high, dry kames deposited by glaciers. Strathcona Science Park, a provincial park in East Edmonton that is now inaccessible to the public, was once the site of a large lithic workshop, a place which was regularly utilized for stone shaping. During the warmer months of the year, technologically inventive Indigenous people camped at the site to gather and hone materials. Here, not long ago, quartzite (a metamorphosed sandstone) and petrified wood cobbles were masterfully chipped down into hand-held hide scrapers, light weight arrow heads and other tools.

Smaller prehistoric period campsites have also been discovered, and disturbed by progress, at Rossdale Flats and the Walterdale Bridge replacement site. These river edge, lower elevation camps were likely temporary stopovers, used by small groups in search of stone materials to make tools. Stone hearths and the debris of daily life were left behind as a reminder that a technologically and culturally rich portion of humanity existed here long before us.

Atop the spruce and aspen forested knolls, families found safe haven from raging winter squalls, while the grassy plains hosted larger groups gathering for trade or ceremony during the summer months. It’s no wonder, then, that the east-flowing waters of the North Saskatchewan would become a superhighway for European trade and exploration. Nor is it much of a stretch to comprehend how these lands, surrounded by mixed forest and nutrient-rich floodplains would become a headquarters for commerce and settlement by immigrants from Europe. The puzzling part of the history we share is how the settlers failed to heed the warnings of their Indigenous hosts, how a millennia of experience was overlooked putting thousands of people in peril?

The land, as it has always done, shapes the lives of the people it supports; since the beginning of time, our identity and uniqueness is formed by the places we live. Waterways have the same power over humanity, the capacity to govern and alter our lives, to forge and destroy our human efforts with a single event. The human ability to respond, and to adapt over time, was forged in the throes of sudden and uncontrollable change, with events that either defeated us or made us stronger. This place, and the river that runs through it, has altered us; it has shown us how to live, how to evolve and how to flourish despite events beyond our control.

Jenna Chalifoux © 2016