Edmonton is a city covered in names. From Capilano to Calder, from Delton to Duggan, from Ermineskin to Elsinore, our neighbourhoods, parks, and roads are a shorthand guide to the history of our city.

But one place you won’t find many names is on the street signs of central Edmonton. There’s Jasper Avenue, named after fur trapper Jasper Hawes. There’s Whyte Avenue, named after CPR vice-president Sir William Whyte. But apart from these two illustrious examples, our downtown grid is awash with numbers, not names.

Once you learn how Edmonton’s street system works, it’s very easy to navigate. You need only look at an address to know exactly where to go—for example, 10440 108 Avenue tells you that you need to go to the northwest corner of the intersection of 104th Street and 108th Avenue. Compared to cities like Toronto and Montreal, where you have to memorize every named street, it’s a remarkably coherent system.

But it hasn’t always been this way. There was once a time when chaos reigned supreme over Edmonton’s street names. A time when there was no Google Maps to guide us through the labyrinth. A time when Edmonton wasn’t one city, but two.

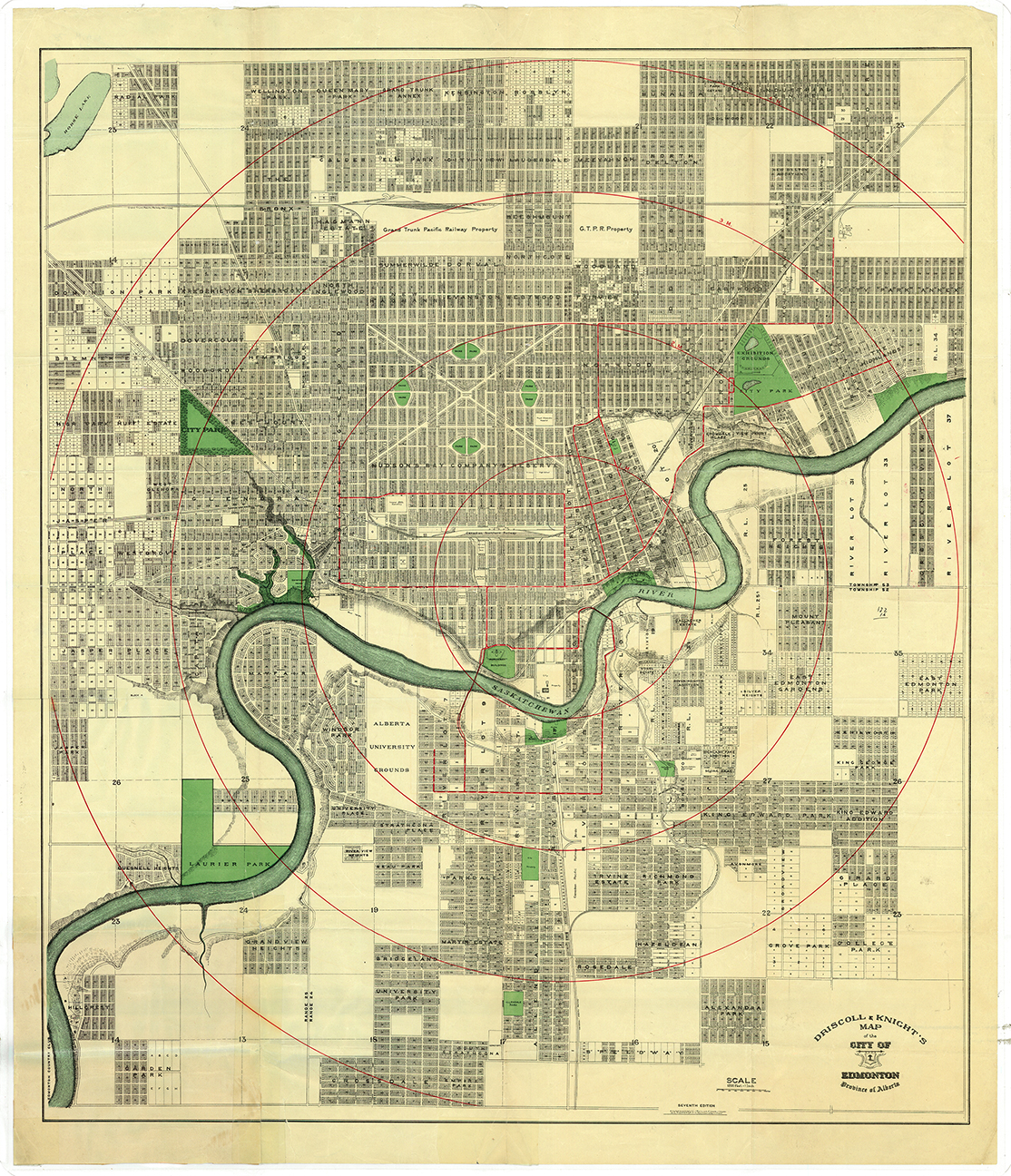

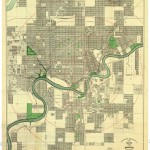

The merger of Edmonton and Strathcona in 1912 created a huge amount of confusion. Suddenly, dozens of street names were duplicated on either side of the river. To make things even more complicated, the new city was in the midst of a development boom, with new neighbourhoods and subdivisions popping up every week.

“The naming of streets was left entirely to the discretion of realtors, there being no control on street naming. Not surprisingly, this resulted in a haphazard, confusing and often repetitive system of street identification” (Naming Edmonton xxiii).

Developers created street names to market their neighbourhoods, to advertise prominent businesses, even to honour members of their families.

“One street might have six different names as it crossed the city; a different name every twelve blocks,” writes Tony Cashman in More Edmonton Stories. “By 1913, it was clear that something had to be done.”

Mayor William Short and city council decided to act unilaterally and without public consultation, introducing the numbered street system that we use today. Jasper Avenue and First Street became 101st Avenue and 101st Street, anticipating the growth of the city and imposing a rigid structure on its roads. In 1913, the City started tearing down its named street signs and installing standardized number signs instead.

But Edmontonians had grown attached to their named streets, and the backlash was instantaneous—the biggest point of contention being that the new system placed 1st Street way out on the east end, whilst visitors would expect it to be downtown.

In the fall of 1913, A. R. Lawrence, owner of the Bijou Theatre, launched an injunction against the city to stop the street redesignations. He demanded a plebiscite on the issue. Two months later, Mayor Short was voted out of office, the first time an incumbent mayor had lost an election in Edmonton’s history.

To appease an angry populace, city council decided to launch a public contest: a $100 prize to the best plan for renaming Edmonton’s chaotic streets. They received over 200 submissions, and tacked up their half-dozen favourites on the walls around the council chamber. Eventually, a winner was chosen: the Edmonscona Plan.

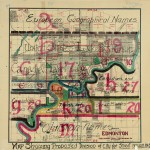

Developed by Dr. D. G. Revell and George Gowan, the Edmonscona Plan retained the downtown street names and numbers that everyone liked, while also providing for the possibility of expansion. Outside of downtown, it divided up the city into districts with imaginative and colourful themes.

Avenues north of Jasper were to be named for rivers, ascending alphabetically from Athabasca through Danube, Orinoco, and Thames. Streets in the east end would be named for famous cities of the world—97th becoming Aberdeen, 96th becoming Boston, and so on through Glasgow and Halifax and Winnipeg. The streets west of 104th Street in Old Strathcona (AKA Main Street AKA Calgary Trail AKA Strathcona Boulevard) extended into the University grounds, and so they would be named after great poets and authors: Byron, Dickens, Homer, Milton. Lakes and seas, mountains and trees, historical characters and provinces of Canada—the Edmonscona Plan included them all.

Revell and Gowan promoted their plan at a half-dozen public hearings, and eventually their whimsical and original naming system won over a skeptical city. But factions of city council were still enamoured with Mayor Short’s 1913 numbering scheme. A special committee approved the Edmonscona Plan, but at least one of the aldermen claimed to have voted for it just because he wanted to show how much better the Short plan was in comparison.

Maps were put up in post offices throughout the city so that citizens could see the two plans side by side. On April 6th, 1914, the city finally held the long-awaited plebiscite to determine which plan would prevail.

“Which do you favor:—

- The all-numerical scheme of 1913 whereby large numbers are in the centre of the city.

- The scheme of Edmonscona, partly numerical and partly names, and giving small numbers in the two centres of the city, one on each side of the river.”

– The Edmonton Capital, April 3rd, 1914

It was a battle between the functional or the fantastical, the pragmatic or the poetic. Would Edmonton be a creative, romantic city covered in distinctive names? Or would it succumb to boring utility?

In the end Mayor Short’s 1913 Plan won by six hundred votes. The Edmonscona Plan, for all its grandeur, for all its infinite variety, failed to win over the hearts and minds of Edmontonians.

In spite of the plebiscite’s results, criticism of the 1913 Plan persisted.

“People can’t remember these big numbers,” said Alderman Joseph Henri Picard in 1915. “I know I cannot, for I can’t even tell where the streetcars are going. We don’t want to be given numbers like convicts who have no reason to be known by their names” (Edmonton Bulletin, December 1st, 1915).

Petitions were circulated and presented to council, furious letters to the editor were published. But with renewed confidence, the city resumed its redesignation of the streets, creating the numbered grid system that we use today.

© 2016 Bruce Cinnamon