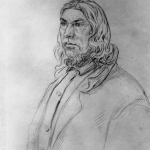

James Bird Jr. (1798-1892), also known as “Jemmy Jock Bird,” “Jimmy Joke Bird”, “Jamey Jock Bird,” and many variations in between, was a man of many languages. Bird spoke at least seven: Cree, Stoney, Sarcee, Blackfoot, French, as well as the English he had learned from his father. Even at his death at an advanced age, Bird’s English still had a “lingering echo” of an English Middlesex accent. During his long life, he interpreted for the Hudson’s Bay Company, the American Fur Company, Christian missionaries, and even at treaty negotiations both north and south of the 49th parallel. Bird made his living mediating between not just language groups but between cultures: an essential role in the pluralistic society of nineteenth-century Fort Edmonton.

The majority of documents produced out of Fort Edmonton in the first half of the nineteenth century were in English, destined to be read by English-speaking Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) employees or London executives. Many travelling journals were equally published for English-speaking readers. These documents give the misleading impression that English was a widely spoken language in the Saskatchewan District at this time. This was not so. The artist Paul Kane complained in his description of Christmas dinner at Fort Edmonton in 1847 that he could only understand a handful of people at the head table: the only ones who could speak English. Cree, Blackfoot, French, Gaelic, and various First Nations languages were far more commonly heard than English along the North Saskatchewan River. To do business at Fort Edmonton and beyond, one needed either to speak Cree or Blackfoot or employ a reliable person who could.

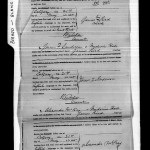

Born near Prince Albert, Jemmy Jock Bird was raised at Fort Edmonton and educated at York Factory. Bird was named for his father, James Bird Senior, who worked for the HBC out of Fort Edmonton before becoming Chief Factor of the Red River District. Bird Jr. first learned his Cree from his mother, a woman named Oomenahowish (“Well-dressed Woman”). He learned Blackfoot after spending many years living among the Peigan (Piikani). He married at least one woman, Sally, of that nation, though the number of wives Bird married (sometimes more than one at once) is not always clear from the records.

Bird was widely regarded as one of the only people at Fort Edmonton – and large parts of what is now Alberta – who could interpret the language of the Blackfoot reliably. White contemporaries, however, almost universally viewed Bird with distrust. Governor Sir George Simpson once described him as “one of the most worthless of his breed,” despite hiring Bird for trusted missions to secure the Peigan trade. Beyond untrustworthiness based on his independent attitude and flexible loyalty to the HBC – which did not always provide steady employment and pay – rumours circulated between trading posts of Bird’s involvement with murders and other violent acts. Regardless of their basis in reality, the fact that many people believed the stories and thought of Bird as the kind of man who would shoot a man in cold blood, scalp him, and carve a message into the dead man’s forehead speaks to his fierce reputation.

Despite these rumours, Bird was also employed by several missionaries to Rupert’s Land. French Catholic Father Pierre-Jean de Smet wrote in 1845 that his “greatest perplexity is to find a good and faithful interpreter; the only one now at the fort [Bird] is a suspicious and dangerous man: all his employers speak ill of him – he makes fine promises.” John Rowand, Chief Factor of Fort Edmonton, wrote a belated warning to de Smet when he heard of his decision to hire Bird – “Beware, my good sir, of your interpreter Bird. He hates everything connected with the French or Canadians.”

Reverend Robert Rundle was another missionary who had no other option but to hire Jemmy Jock Bird so he could try to convert the Blackfoot, writing that “there is no one else in the Territory qualified for the task.” At first, Rundle’s journals show nothing but earnest and perhaps naïve enthusiasm for his mission. But then, suddenly, Rundle realized just how reliant he was upon his interpreter to communicate and how important it was to remain in Bird’s good graces. In his journal entry for April 20th, 1841, Rundle describes how he:

“Passed thro’ a most trying scene of my missionary life; my interpreter refused to help me. In vain I sent for him & went to him; he was quite obstinate. At last, after much entreaty, he helped me at one service but no more. Wind very high which at times completely drowned my voice.”

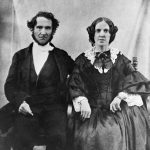

Bird was an independent man and would brook no disrespect. From Rundle’s own journals, it was clear that the missionary was not an easy employer. Rundle tried to forbid Bird from speaking with anybody in camp except when he was directly translating Rundle’s words. Rundle preached about the sanctity of marriage, knowing full well that Bird kept two wives. Rundle also repeatedly refused to baptize one of Bird’s wives, Sally, who was sincere in her desire for Christianity but whom Rundle perceived as living in sin. Bird knew the value of his services. Without an interpreter to translate the languages of the First Nations majority into English for him, Rundle was helpless.

Bird still worked for Rundle off and on after this incident. Rundle still needed Bird’s services, because as an English speaker in Rupert’s land he had limited means to communicate without an interpreter. Bird still occasionally refused to translate after quarrelling with the missionary. Rundle seemed paranoid that Bird was undermining his religious work, noting with worry that Bird “spoke a little by himself, I believe,” or “I thought his conversations with them had a tendency to counteract my efforts amongst them; in short that he was giving them bad advice.” Despite Rundle’s occasional suspicions that Bird was damaging his work among the Blackfoot, they continued to work together for years. Rundle often hosted sermons to the Blackfoot in Bird’s tent and while the missionary continuously refused to baptize his wife, Rundle did baptize Bird’s children and even helped to bury one of his daughters after her death. The relationship between missionary and interpreter was not always antagonistic, though Rundle continuously worried about how his English words were being translated into languages he did not understand.

At its height in the nineteenth century, the Hudson’s Bay Company post at Fort Edmonton was a commercial hub along the North Saskatchewan River and, just like in the modern city of Edmonton today, people of many languages and cultures gathered there to live and do business with each other. In such a context, Bird’s translation skills were much in demand. Being an interpreter was a trusted position and words had far-reaching impact. Bird was not an easy man to work with – but then again, neither were many of his employers. Bird’s command of both Indigenous and European languages made him a valued asset to those who chose to employ him. But his close association with the Blackfoot people – one of the reasons he was so valuable as an interpreter – also made him suspicious to his European employers. He was employed when needed and sent on his way when he was not. Bird was not treated as an Englishman, despite his parentage, his Christianity, and his Middlesex accent. When treated poorly by the HBC, he would work for a time with their commercial rivals. If slighted by an arrogant missionary, he would withhold work. If he could not find a position as an interpreter, he would pack up his family onto a horse-drawn cart and head out onto the prairie, herding horses to sell and relying upon the great bison herds for food. Jemmy Jock Bird needed to rely on no-one to navigate the multi-cultural society of the West. He had the skills to make his own way in life.

Resources:

Dempsey, Hugh A., Ed. The Rundle Journals, 1840-1848. Calgary, AB: Alberta Records Publications Board, Historical Society of Alberta, and the Glenbow-Alberta Institute, 1977.

Jackson, John C. Jemmy Jock Bird: Marginal Man on the Blackfoot Frontier. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2003.

Kane, Paul. Wanderings of an artist among the Indians of North America: From Canada to Vancouver’s Island and Oregon through the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territory and back again. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts, 1859.

© 2016 Lauren Markewicz