As we go about our daily lives, driving the kids to school or walking the dog, we often forget that the places we know were once very different than they are now. When the sidewalks are strewn with an autumn rainbow of leaves, golden and russet and red, we might not think of who set that seedling in the ground so our child may frolic so joyfully. Our neighbourhoods are more than just roads, schools, churches and coffee shops, for our homes stand on a solid foundation of the lives of others who lived before us. The places we know remember them all, the ground we walk on carries the toil and heroics of those that survived the frigid winters and laboured each spring to bring forth the abundance the land is so willing to share. In turn, the places we know are transformed by us, just as we are shaped by them.

In 1870, the entire population of what would become Alberta was a mere 8,000 individuals, 6,000 of which were Indigenous people of various tribes scattered throughout the western prairie lands. The Census of Edmonton and Neighbourhood in April of 1874 recorded at total of 93 ‘halfbreed’ men, women and children living in the area of Fort Edmonton. The remaining 43 ‘white’ citizens included 2 women and 4 children. This is not particularly remarkable for the era, as most communities were derived from fur trading forts in which relationships with Indigenous peoples were vital to both commerce and safety. As commonplace as it was for European bred men to marry women who carried Indigenous bloodlines, their children were still recorded as non-white citizens. Accounted for were some of modern-day Edmonton’s neighbourhood and byway namesakes such as Rowland and Hardisty. The infamous and twisting Groat Road, named after Scotsman Malcolm Groat, can boast of its Indigenous foundations as Mrs Groat and their three children are marked in the document as halfbreeds. Other families included the Laroques, Berards, Birds, Whitfords, McDonalds and Frazers; all (in varying degrees) were natives of this land, their kinsfolk thriving through time, no matter the hardship they adapted and continued their legacy. In a total recorded population of 136, 14 men, 23 women and 56 children were noted as having Indigenous roots. Throughout these documents, the names of both Indigenous and half-breed families easily outnumber those of the European ancestry. As the land allowed, nations of the Old and New World were represented in the citizenry of the growing metropolis from it’s inception; together the Dene, Cree, Stoney, Blackfoot, French, English, Scottish and Irish built this city of champions.

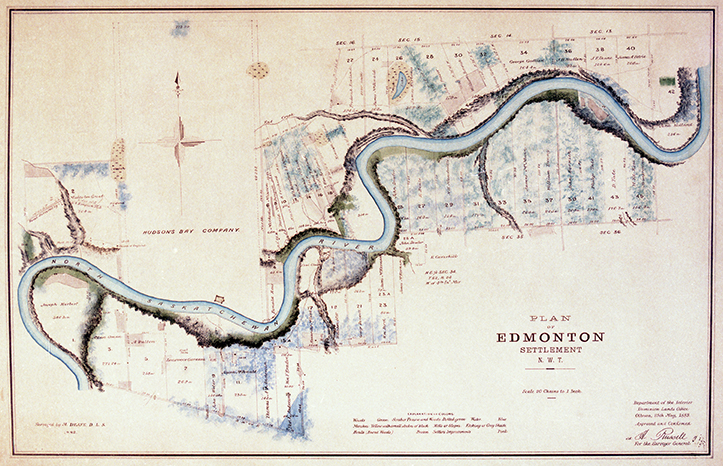

Between 1870 and 1905, when Alberta became a province, the neighbourhood now known as Garneau continued to see an influx of Indigenous groups, Métis homesteaders and European settlers. Hawrelak Park, the emerald oasis of Edmonton’s river valley park system, was officially surveyed in 1882 and noted as Lot number 1. Quebec born, Joseph Hiebert had been farming the land since the early 1870’s. Edmonton families have the unheard-of Frenchman to thank for clearing the lands we now use for golfing, picnics, paddle boating and Autumn leaf play. Riverlot 3, roughly the area between Groat Road and 116th street, was purchased by Allan Oman, a riverman and boat builder of Scottish descent, in 1883. He and his three sons mined the coal seams that can still be seen along the riverbank on the trail between Emily Murphy Park and Kinsmen Park. Vaguely remembered Arthur D. Patton, a farmer of Irish descent, held the original deed for Lot number 5, the land that lays between 116 and 114 streets, or thereabouts. The 1881 Edmonton District Census shows Patton was 26 years of age and unmarried. Born in Quebec in 1855, then raised in Toronto, he was still living with his parents in 1871. In a mere ten years, he had made his way 3,000 kilometres west to Edmonton and staked his claim on the southern banks of the river. He eventually sold the land to Isaac Simpson who’s farm became quite renowned for both livestock and crops. These men, and the women who shared their lives, saw something in the land that inspired hope. In the fervour to settle, their vision of themselves became altered, the land became their future and in turn their strength and struggle, blood and sweat transformed the earth forever.

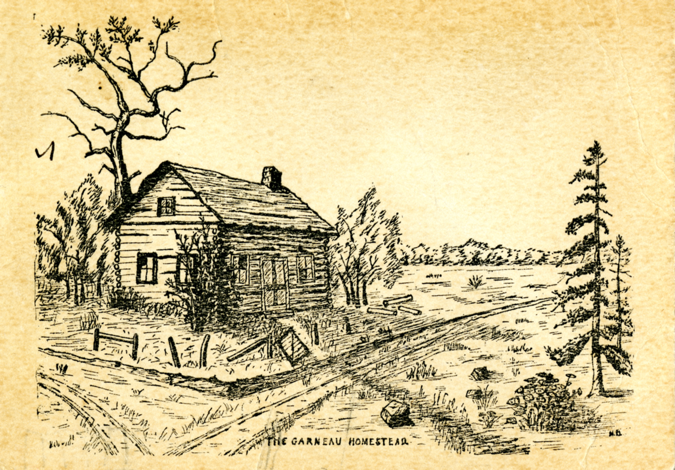

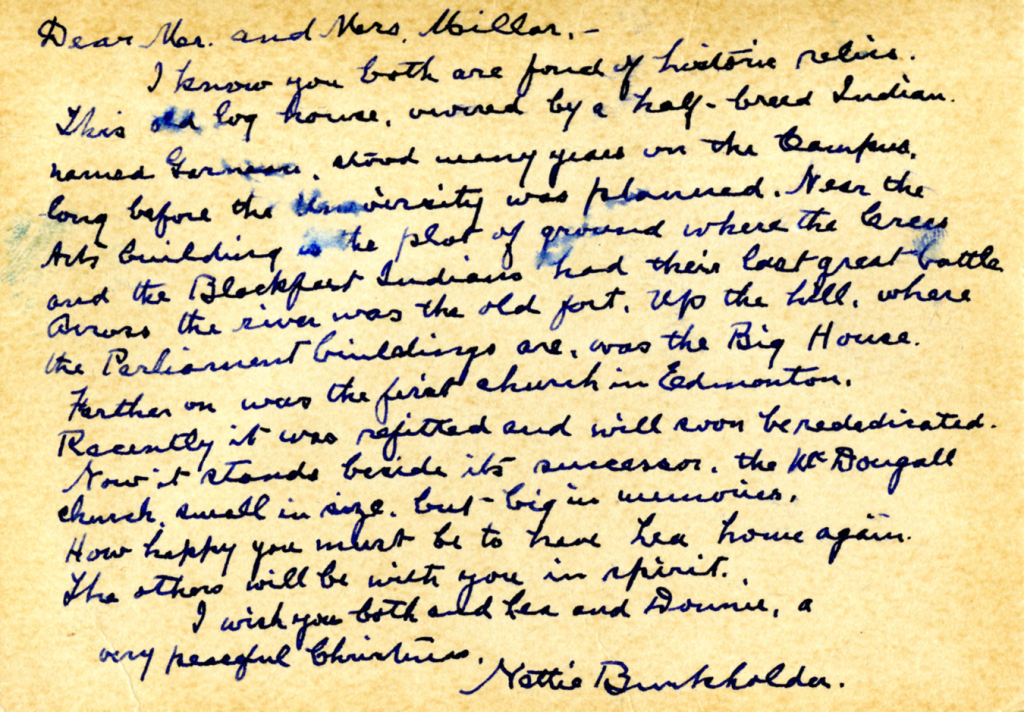

Laurent Garneau, the Métis namesake of the now quaint neighbourhood, arrived in the spring of 1874. Having left behind his wife, children and all their belongings, Laurent pitched his canvas teepee and went about clearing a space upon which to build a home. His family had come from the east, leaving the Red River settlement behind after the chaos of the Métis Rebellion against the crown. Although his Indigenous loyalties never strayed, he longed for a place, a piece of earth to establish roots. He and his wife, Eleanor, raised more than a dozen children on Lot 7, the swath of land stretching east from 112th to 107th street.

Through the years, Laurent became known for his egalitarian nature; he enjoyed playing his violin at gatherings no matter the host and always allowed those who could not afford the cost of barging goods over to the fort access to the shallow watered fords below his homestead. A man of all nations, he was respected by his Indigenous, Métis and European counterparts. In 1901, the Garneau family moved to Saint-Paul-des-Métis where they continued to flourish. A glimpse of this history can still be savoured, the industry of Laurent and his family lives on in the tenacity of a single maple tree that grows in the HUB Mall parking lot at the University of Alberta. Laurent Garneau was a man of two worlds; while his ancestry belonged to separate landmasses he found a way to meld the values of his Indigenous mothers with the goals of his forefathers. His magnanimity ensured his place in his community and ensured his name would remain connected to the land far into the future.

The places we know have an identity. As with people, places are defined by the characteristics, both tangible and intangible, that make them unique. Places have a past, they carry memories and have transformed throughout time. The land and its people carry a history and an identity that are forever intertwined.

© 2015 Jenna Chalifoux