Waste may be as old as humanity, but the idea of trash is a relatively modern concept. In the first years of the twentieth century, the citizens of Edmonton and Strathcona simply tossed their garbage out into the street or lane. While the accumulation of what was politely known as “night soils” became a public nuisance, other forms of waste were reused, recycled, or turned into toys. Scavengers, scrap metal dealers, and rag and bone men worked the city streets for used tins, linens, and boards. And what remained could easily be pushed off a bluff into the North Saskatchewan River.

Early twentieth-century urbanites took a rather sophisticated view of waste. Slops, ashes, and garbage were viewed as separate categories and treated differently. Ashes, which included all kinds of burned matter, could be reused, like road crush or gravel, as a base layer for streets and sidewalk. They could also become compost or a cover for the foul stench of night soils. Slops, on the other hand, formed part of a virtuous circle that fed the passels of hogs wandering the city streets. Hotel and restaurant owners could sell their slops to feed the pigs, who were in turn sold back as food. Garbage, however, might have been the most valuable category of waste, as it contained rags, boards, glass, and metals that could be bought for scrap or recycled into other household goods.

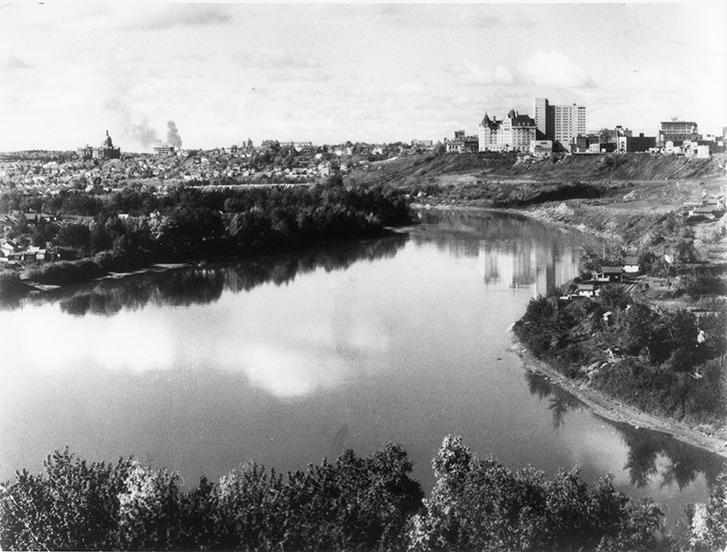

It was the prospect of reusing and repurposing garbage that gave rise to Edmonton’s largest and longest-lasting shantytown, on Grierson Dump. While Edmonton was one of the first western cities in North America to create a vast waterworks infrastructure, it lacked any civic strategy for dealing with waste. Large items were simply pushed off the bluff near the Hotel Macdonald and left to tumble into the river valley. Many unemployed immigrants realized they could reuse this material to build their own shacks and eke out a living finding the odd treasure in the dump. During the Depression a reporter from the Edmonton Journal interviewed a few residents who had been living on the dump for decades, earning about $2 a week. One Dutch immigrant called Smitty was particularly notable for turning garbage into handmade flower pots and picture frames.

Grierson Dump was not only a convenient place to ditch unwanted items but also a landfill that, according to the City Engineer’s office, mitigated the precariously steep nature of the river bank. The City Engineer in fact encouraged the dumping of waste down Grierson Hill, even though the conditions there provoked the ire of Health Department, the Police Department, and the Fire Chief. Residents from McCauley and Boyle Heights complained of the smell, but were simply told to keep their windows shut on particularly bad days.

The reality of a growing dump just below the city centre led to a number of crises, and in 1911 the City Commissioner made the first of many attempts to shut it down, citing multiple “nuisances.” Investigators sent by the North West Mounted Police concluded that typhoid and other public health “menaces” were breeding at the dump. An incinerator was built to burn waste from the newly built Royal Alexandra Hospital, but businesses in the city centre resisted paying to have their garbage removed so far north.

Tension came to a head in 1913 when a cholera epidemic swept through the population of hogs who fed off the slops at Grierson Dump. The pandemic was devastating for the hogs and led to a panic among the citizenry, who feared (erroneously) that the outbreak would spread to humans.

In any case, the great hog cholera epidemic led to the temporary closure of Grierson Dump to slops. The dumping of everything else was still permitted, however, and the practice of scavenging carried on. The Edmonton Capital editorialized in 1913 that “the citizen should realize the scavenging begins with him,” and that people should distinguish between rubbish that “had a commercial value” and other forms of waste.[1] At the time, scavenging was thought of as an important civic activity, and as late as 1916, was still an official city job managed through the Streets and Scavenging Department. One Mr. Schunke, who held the title of City Scavenger at the time, blamed outsiders for the problems at Grierson Dump and urged civic leaders to keep it open.[2] Some citizens floated the idea of building a massive wall to separate Edmonton from its landfill in the river valley, but the plan appears to have been abandoned during the economic bust of 1915.

The very notion of what constituted trash continued to be subject for debate in 1917, when Edmonton passed a by-law regulating the collection of garbage. Residents would be limited to disposing of one cubic yard or a hundred pounds of waste per week. No longer would feeding slops to hogs be tolerated. In fact, it became a criminal offense, even though defenders of the practice promised to properly cook waste before feeding it to the swine.[3] City Councillors hoped that the ever-expanding mass of garbage at the river banks would eventually be dealt with by a massive incinerator that would burn it all, but the construction of a city-wide incinerator was judged too expensive.

A similar proposal for an incinerator had been put forward in 1911 in Strathcona, where sanitary conditions appeared to be even worse than in Edmonton. Waste collection was entirely in the hands of scavengers, even though the Board of Health saw the practice as unsanitary. Residents of Strathcona were given pails for their night soils, and the practice of dumping these pails in laneways had created such a mess that the Board urged the city to discontinue the practice and build sewer lines that would naturally slope down to the river. In the meantime, the Strathcona City Scavenger would have to manage by sweeping waste into holes on city streets until it could be carted off.

In 1917, Edmonton’s mayor got the bright idea to hire workers to bury the waste at the Grierson Dump rather than let it fester like an open wound. Workers put ashes on top and began sending manure further east down the river valley. As the city grew, the dump expanded westward, encroaching on neighbourhoods near the Legislature. The city continued to advise people to just keep their windows shut until [4] 1929, when regular residential garbage pick-up finally began.

Even then, Grierson Dump persisted as both a shantytown and an informal marketplace for secondhand goods. Much of the dump’s economy centered around the Alberta Motor Boat Company, near present-day Louise McKinney Park. While the City Engineer saw the dump as a useful buffer between the river and the city, the Fire Department was struggling to deal with fires resulting from “spontaneous combustion.” In 1929, a fire that broke out near the Alberta Motor Boat Company took eighteen hours to put out. The Fire Department was sick of the dump and urged the city to close it for good.[5]

But the shantytown only expanded during the Depression. Unemployed men wanting to receive relief from the government were expected to report to work camps, and many preferred a life of relative freedom on the dump to the indignities of forced labour. The city sent investigators into Grierson in 1933 and found dozens of immigrants from Scandinavia and Eastern Europe who had refused relief but had built shacks–”bachelor apartments”–from sheet metal, wire, and cardboard. They were heated with coal lamps and had no running water or electricity. The men dug much of the coal out of the hillside, a practice that got them dubbed “cavemen” by one Edmonton Journal reporter in 1935.

As the worst years of the Depression passed, even the City Engineer began to advocate for the closure of the Grierson Dump and the eviction of its residents. In 1937, City Engineer A. W. Haddow complained to the City Health Department about his inability to move people off the dump. The city had repeatedly destroyed the shacks only to see them rebuilt by the sixty-five or so residents each time. “I think the only way we can get anything done is to have the police take action and have them out of here,” he wrote. “I think they are not only interfering with the work we are doing in the way of the river bank protection, but are a menace to public health as you suggest.”

Finally, by the end of the decade, Grierson Dump was set to close. The residents were sent an eviction notice that told them they were a “menace” to public health, and the Fire Department was informed that everything on the dump would be burned. By 1943, the city had outlawed the keeping of chickens and pigs within city limits. Passels of hogs feeding on slops in the city streets were now a thing of the past. As the city prepared for a post-war future, all sorts of garbage became trash, a broad category of stuff to be dumped into a metal can and carted away, preferably to an incinerator, where it would vanish into the air, never to be seen again.

© Russell Cobb 2015

Read the next piece in Dr. Cobb’s series Edmonton: A World Class Dump, entitled Feel the Burn: Edmonton’s Curious Love Affair with Incinerators

References

[1] Edmonton Capital, December 27, 1913, p.9.

[2] The Edmonton Bulletin, July 27, 1904, p.5, Ar00505.

[3]http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDB/1917/09/26/3/Ar00302.html?query=newspapers|garbage|%28pubyear%3A[1871+TO+1918]%29+AND+%28publication%3ACDW+publication%3AECR+publication%3AEDB+publication%3AEDC+publication%3AGAT+publication%3AMRR+publication%3ASCC+publication%3ASDN%29|score

[4] The Edmonton Bulletin, December 22, 1923, Page 5, Item Ar00516.

[5] The Edmonton Bulletin, October 19, 1929.