Continued from Retrofutures: Edmonton’s Omniplex – Part 1

This moment in Edmonton’s history happened to coincide with one of the most remarkable events in the history of sports architecture. In 1964, Houston, Texas, another city riding high on an oil boom, completed the Astrodome. Edmonton coliseum boosters went on a North American tour of sports facilities, traveling to Montreal and Detroit, among other cities. But it was Houston that most impressed them. It would be hard to overstate the awe that the Astrodome inspired during the Space Age. The building, known as the “Eighth Wonder of the World,” quickly became one of the symbols of modern Houston. For years after its completion in 1964, it was the third-most-visited man-made tourist destination in the United States, after Disneyland and Mount Rushmore. As late as the 1980s, visitors could pay a dollar to gaze upon the interior when no events were being held.

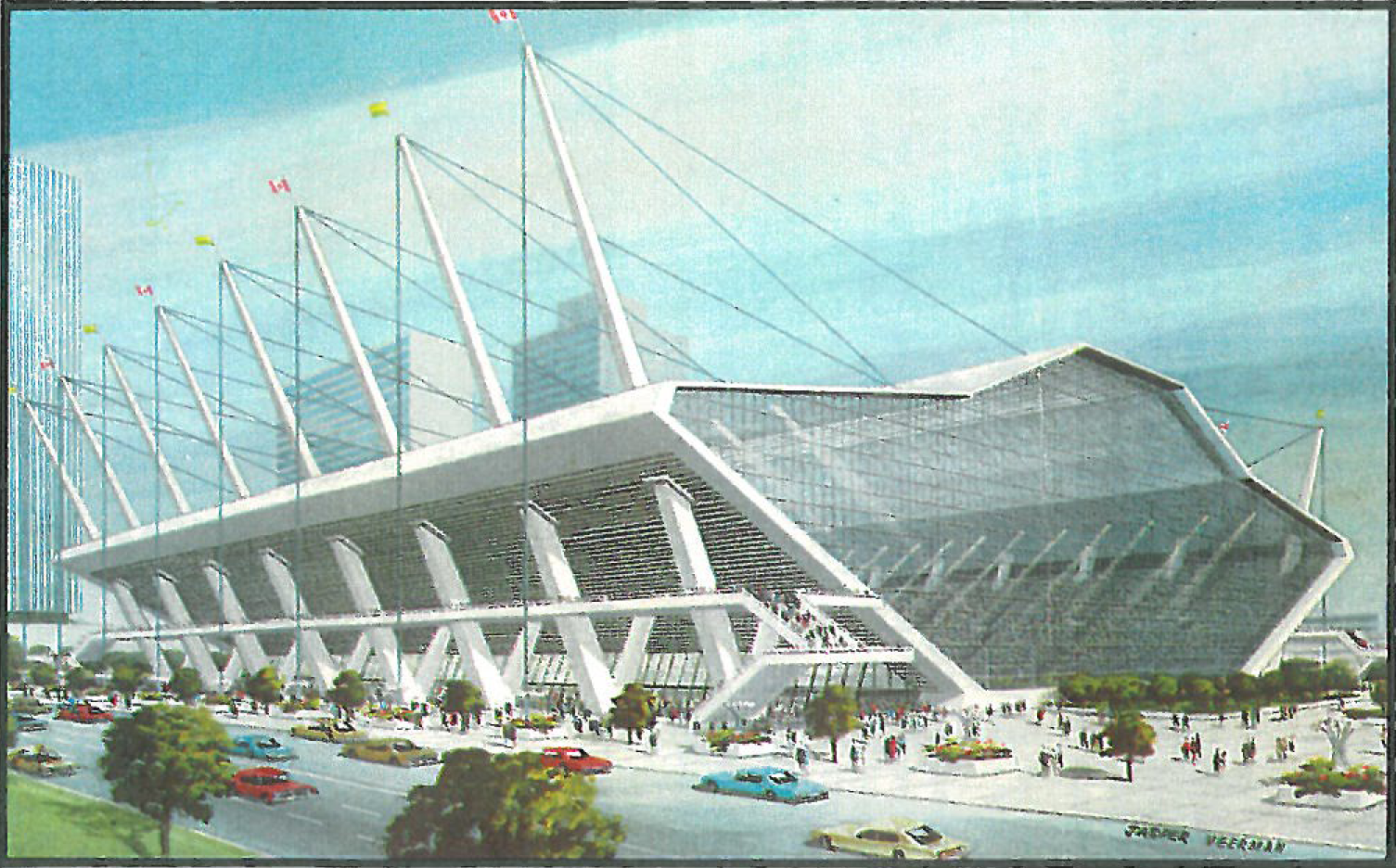

Infatuated by the Astrodome, Edmonton introduced the concept of Omniplex in 1967. Rather than build an outdoor football coliseum, Edmonton would build an all-encompassing arena for every sport imaginable, along with a convention centre and entertainment facility. A pamphlet boasted that Omniplex would even best its rivals in Montreal and Houston. “Proposed is a structure unlike any other in the World,” an Omniplex brochure stated, “as bizarre in concept as the Expo Pavilions and many times more versatile – as well as much more weather-proof – than the Houston Astrodome.”[1]

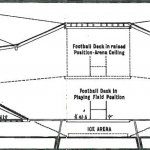

There were, in fact, many different plans for Omniplex, and various investors sponsored proposals for the designs. At City Hall, aldermen considered an array of futuristic designs. The most inventive of all, and the most publicized, was the Marlboro Plan. This vision featured a circular structure of glass walls and concrete pylons that supported a domed steel roof. An ice rink lay below the football field, which was tracked on hydraulic elevators. The football field could be raised to the ceiling of the stadium, revealing a hockey arena with a seating capacity of between 7,500 and 15,500, depending on demand (and depending on how high the field was lifted). The trade and convention space was tucked away underneath the stands, and a plaza area with specialty restaurants overlooked the 32,000-seat football stadium.[2]

Another plan–the Batoni Plan–included a cable-suspended roof and integrated the hockey arena into the football field by covering the ice with removable AstroTurf. The Hashman Plan employed mechanically movable seats on a sunken track in order to offer the best possible viewing for both sports, a technique borrowed from the Astrodome.[3] As grandiose as the plans were, the rhetoric around Omniplex may have been even more hyperbolic. A full-page ad in the Edmonton Journal in 1968 touted the facility as “a Machine for Selling Edmonton to the World.” Boosters estimated that Omniplex would have a similar effect on Edmonton as the Astrodome had on Houston. At least four new hotels would be built downtown. Tourists would flock to Edmonton, curious to see the most modern building in North America. When some citizens started to grumble that the plans for Omniplex would have no effect on ordinary Edmontonians, supporters put together an imaginary narrative to help sell the idea. Perhaps most importantly, Omniplex would tackle the problem of urban blight.

“Who benefits?” the official Omniplex pamphlet asked. “Each citizen, as a modern multi-use complex revitalizes city core, dramatically increases adjacent tax assessment while providing a structure for use and enjoyment of all citizens and for attraction of new industry.”[4]Bud Squair, president of Edmonton Community Leagues, wrote in the Journal that “Omniplex is a form of urban renewal which will bring about a rapid redevelopment of the eastern sector of Edmonton’s downtown core.”[5]

A Night on the Town with Harry Cogill and Family

One of the many advertisements for Omniplex told the story of a fictional man named Harry Cogill, an ordinary Edmontonian whose quality of life would be greatly enhanced by Omniplex. The ad imagined Mr. Cogill’s plans for the evening. “Harry Cogill has the evening planned – a guided tour of Omniplex starting at six o’clock, dinner at seven, and the game at eight (all within the same building!). The specialty restaurants are open, the retail stores…boutiques, book stores, cocktail lounges… they are all alive with life!”[6] Harry marvels at “the grandeur of the building,” the “mechanized cloakrooms,” the “color décor, spaciousness…can the concourse alone ever be over-crowded?”

“When the Cogills step into the lobby,” the ad continued, “it is air-conditioned…in the middle of November.” The Cogills later attend an Eskimos game where they sit in “comfortable seats – complete with padded arm rests! True comfort for a shift-sleeve crowed at a November football game. Harry Cogill shivered at the thought of that late-season Eskimo game a year ago…but, tonight he and his family have joined the rest of Edmonton in coming in out of the cold.”[7]

Apart from providing entertainment for Edmonton, Omniplex would conquer the elements, making the citizens of North America’s northernmost city forget–at least temporarily–their harsh climate. It would change Edmonton’s identity from a frontier city in the frozen north to a comfortable and cosmopolitan destination with the most modern amenities available in the world.

The idea that a sports arena could serve as a “Machine for Selling Edmonton to the World” might strike the contemporary reader as curious, but it reflected the zeitgeist of progress as mechanization and efficiency. Omniplex was not the only “machine” of the time. Earlier in the 1960s, the Edmonton Journal described the hyper-modern International Terminal at the new airport as a “giant sorting machine” for people. The French architect and urban planner Le Corbuiser once theorized that the city of the future would be a “machine for living.” By the late 1960s, Edmonton appeared to be realizing this dream.

The Fall of Omniplex

For all the praise and hope Omniplex generated, the extravagance and ambitiousness of the proposal ultimately jeopardized its practicality and financial feasibility. The NHL president at the time expressed concern that the sports arena could not meet professional hockey standards, and the utilities committee agreed that the logistics of raising an entire football field to the ceiling would be impractical if not prohibitive. Furthermore, the cost to build Omniplex was approaching $32.5 million, while the original budget for the facility was a third of that price. By-election candidate Sam Agronin accused the proposal of being “way beyond the wildest dreams and wildest capabilities of this city,” since the burden of paying for it would fall on property owners. Others worried that Omniplex would exacerbate congestion in the downtown area, and some even questioned whether Edmonton was a big enough city for a 32,000-seat stadium.

Had Ominplex Been Built

(click on this link to see an overlay of

Omniplex on the contemporary city)

Twice, the subject of Omniplex came before the voters. The first time, all registered voters were asked if the city should, in principle, agree to building Omniplex. Seventy-two percent voted yes.[8] On November 25, 1970, City Council brought the issue to the public. In a vote to determine if the government should borrow money to start construction of the Omniplex, 54 percent of property-owning Edmontonians voted no.[9] The city pondered finding alternative funding for the project, but interest petered out as planners began suggesting more realistic alternatives. Four years later, Northlands Coliseum (now Rexall Place) opened, and plans began for a separate convention center on Grierson Hill (now Shaw Conference Centre). The Commonwealth Games of 1978 helped facilitate the building of a football stadium (Commonwealth Stadium).

Had Omniplex materialized into reality, Edmonton might have been stuck with a white elephant. The Astrodome is itself now obsolete, standing vacant and lifeless in south Houston. Even with the city’s muggy, tropical climate, Houstonians decided that they’d rather watch baseball in a traditional ballpark with a view of downtown and in walking distance of bars and restaurants. In 2000, Enron Field (now Minute Maid Park) hosted its first Houston Astros game, kicking off an era of redevelopment that has now made Houston’s downtown walkable and livable. In a complete reversal of urban theory, most planners now seek to encourage density where they once planned wide-open spaces.

While most of the current debate about Edmonton’s new arena has focused on cost and feasibility, city residents are also considering the long-range forecast. Will a new arena enhance the city’s quality of life and its sense of place? Or will it simply become another monolithic concrete-and-steel structure? The new arena—like Omniplex before it—might capture the imagination with its dreams of establishing Edmonton as a world-class city. But for it to sustain itself, it must also capture the needs of a vital, livable city: public space and human-scale retail with safe and walkable streets. Otherwise, it could become Edmonton’s Astrodome—a hulking structure of obsolescence.

[1] “Information Concerning a Proposal for Edmonton Omniplex: A Trade, Convention, and Sports Complex.” City of Edmonton, 1968.

[2] “Another Complex Proposed to City.” Edmonton Journal, March 20, 1968.

[3] Albert P. Morrow, Omniplex: A Report and Analysis of Developers’ Plans, Prepared for the City of Edmonton, October 1970.

[4] “Information Concerning a Proposal for Edmonton Omniplex: A Trade, Convention, and Sports Complex.” City of Edmonton, 1968.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “A Tour, a Dinner, and a Football Game.” Omniplex advertisement published in Edmonton Journal, November 21, 1970.

[7] ibid.

[8] “Recap: Retrofutures – Edmonton’s Omniplex Debate – MasterMaq’s Blog.” MasterMaqs Blog. 17 Dec. 2014. Web. 21 Dec. 2014. <http://blog.mastermaq.ca/2014/12/17/recap-retrofutures-edmontons-omniplex-debate/>.

[9] Ibid.