Many recent projects—the expansion of the University of Alberta, the construction of the West Edmonton Mall, the plans for new Arena District—have been justified by the idea that they will launch Edmonton into the vaunted status of global city. While the present may leave something to be desired, the future in Edmonton has always looked bright indeed.

World-Class Dreams of Omniplex

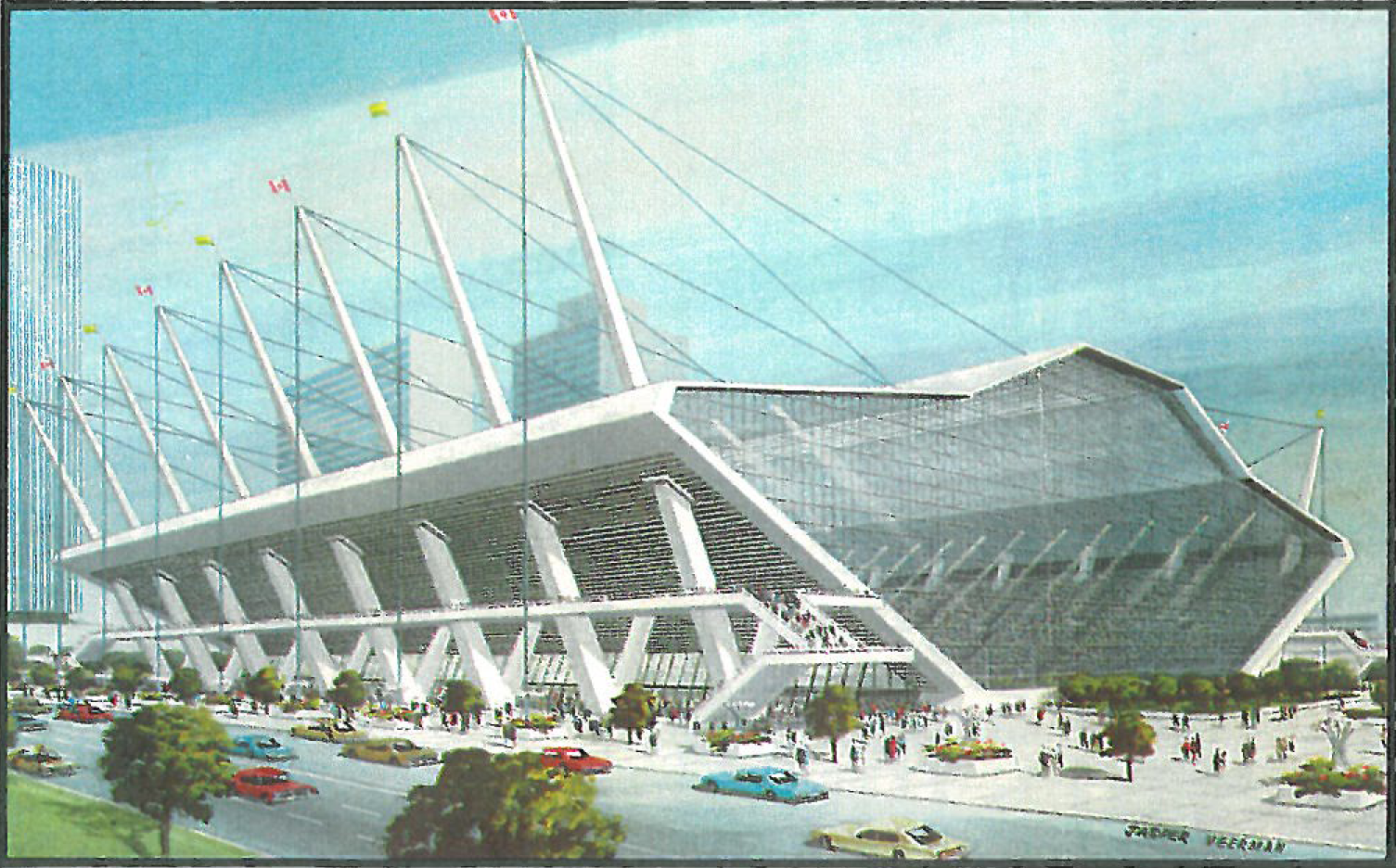

While this desire to become “world class” may seem like a recent phenomenon, tied to the city’s growth in the twenty-first century, it can be traced back at least fifty years. As the city pushes forward with a plethora of redevelopment plans, it’s worth looking back at the city’s most grandiose proposal to catapult it into world-class status: a project known simply as Omniplex. The project might sound familiar: it was to be a downtown sports arena that would act as an economic catalyst, spurring an economic boom, capturing millions of tourist dollars, and boosting civic pride. But Omniplex wasn’t just a hockey arena. It was football field, a convention centre, a concert venue, and a dining destination stacked with luxury restaurants. By the time the models were revealed to the public in the late 1960s, it had morphed into perhaps the most ambitious plan ever hatched for an arena in North America. Alas, Omniplex was defeated in a 1970 plebiscite, leaving behind only the dreams of a full-scale revitalization of downtown. To paraphrase William Faulkner, however, the past of Omniplex isn’t dead; it’s not even past. As urban studies scholars have noted in other contexts, failed projects often have the unintended consequence of generating social movements in opposition to large scale, top-down projects.[2]

So what are we to make of the retro-future of Omniplex? Why did the idea captivate the imaginations of Edmontonians, only to go down in defeat? Is history repeating itself with the new Arena? How different would our city look had we built Omniplex? In this installment of Retrofutures, we examine the rise and fall of one of Edmonton’s most ambitious plans.

Progress and the Problem of Blight

The seeds for Omniplex were planted during the era of the North America-wide urban renewal movement in the early 1960s, when large swaths of old cities were being bulldozed for expressways, malls, drive-ins, and other automobile-centered conveniences. During this time, Edmonton was emerging from a generation of exponential growth. In less than two decades after the end of WWII, the city had built Canada’s first master-planned suburb (Parkallen, 1951) and its first automobile-centered mall (Westmount, 1955). A new City Hall built in the International Style promised to modernize downtown in the late 1950s (and has since been replaced by Gene Dub’s 1992 City Hall building), and a new terminal opened at Edmonton International in 1962. By 1966, Edmonton could boast Western Canada’s first skyscraper (CN Tower). Urban planners and celebrity architects such as Richard Neutra came to Alberta to witness a modernist experiment in urbanism, which touted car-centered mobility, efficiency, and decentralization as the way forward for the twentieth-century city.[3]

There was one big problem, however: two decades of an economic boom and increasing suburban sprawl had left the urban core behind. In 1962, City Council formed a commission to look into the decline of the city centre and suggest solutions. The problem, the commission said, could be summarized in one word: blight. Workers who had poured into the city after the war lived in overcrowded apartments.[4] Some lived in “Dawson Huts,” temporary dwellings that housed American soldiers during the war. The area just east of downtown was crawling with vice, and Edmonton’s first skid row developed around Boyle Street. Of particular note were the “rabbit warrens” of sin around downtown and in the flats of Rossdale. In 1963, the commission developed a strategy for dealing with urban blight, which they defined as a “contagious disease” that was spreading out of control, making the inner city a “stamping ground for delinquency and immorality.” One citizen quoted in the Commission’s report said that in dense neighbourhoods, “[m]en with nowhere to rest in their own homes are forced into the streets and taverns. Children must play on the streets where they are in constant danger from traffic.” Prostitution, gangs, and drug addiction: all of modern Edmonton’s vices shared the common denominator of overcrowding, and by 1964, the city was ready to wipe the slate clean and start again.

Widespread demolition erased the majority of downtown’s brick and wood-shingle pre-war buildings. Density was replaced by spaciousness. Pedestrian-friendly streets would be replaced with “dispersal loops,” designed to move traffic in and out of downtown in the most efficient way possible for automobiles. While downtown was being razed and built again, neighbourhoods close the core were re-engineered following the urban theory of Eliel Saarinen, the Finnish-American architect and urban theorist. Saarinen’s ideas were a major inspiration to Cecil Burgess, the last Dean of the architecture school at the University of Alberta and the so called “Grandfather of Architecture” in Edmonton. Saarinen’s theories have fallen out of favour, but half a century ago he was at the avant-garde of urban planning. Saarinen predicted that after the War, cities would grow in a process he called “organic decentralization.”[5] The gravitational pull of the centre would give way to micro-centres in neighbourhoods as the automobile allowed urban dwellers the freedom to circulate. This process, however, left behind a decaying downtown that struggled to lure locals into its densely packed streets.

As Edmontonians contemplated schemes for revitalization, the city landed on the idea of a new downtown arena. In the early 1960s, prominent citizens started pushing for a coliseum that could suit the city’s two major sports: hockey and football. The Edmonton Oil Kings played professional hockey in a cramped and aging facility officially named the Edmonton Gardens but known unofficially as the “Cow Barn,” owing the building’s first use as an agricultural show pavilion. By 1966, the Edmonton Journal had labeled Edmonton Gardens “a disaster waiting to happen. The old house, with its obsolete lighting fixtures, oily wooden floors, and sordid washrooms, is an eyesore to hockey fans.”[6]

Then, as now, a modern sports arena seemed to promise a new era in civic pride.

To be Continued…

[1]Sassen, Saskia. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

[2] Jane Jacobs’ famous feud with Robert Moses’s plans for a crosstown freeway in Manhattan is widely cited as the beginning of the end of massive, automobile-centered urban renewal schemes in New York City, for example. See Roberta Brandes Gratz, The Battle for Gotham: New York in the Shadow of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs, New York: Nation Books, 2010.

[3]See Trevor Boddy, “Edmoderntown: Four Factors Shaping Edmonton Architecture,” Capital Modern Edmonton.

Accessed December 21, 2014. http://capitalmodernedmonton.com/edmoderntown/.

[4] City of Edmonton Planning Department. Urban Renewal Study for the City of Edmonton: Part 1: The Problem. Edmonton, 1963

[5] Eliel Saarinen, The City, Its Growth, Its Decay, Its Future, New York: Reinhold., 1943.

[6] “Jan. 2, 1982: Thousands Turn out to Mark Demise of Edmonton Gardens.” Edmonton Journal. Accessed December 21, 2014. http://www.canada.com/story.html?id=d122cfdd-885c-4d98-b716-dfd5a49e2cb9#__federated=1.