Decoteau was born on November 19, 1887 on the Red Pheasant Reserve just south of Battleford in present day Saskatchewan. His Cree father, Peter Decoteau, was one of Poundmaker’s warriors at the Battle of Cut Knife Hill on May 2, 1885. His mother, Dora Pambrun, was from the Wuttunee family.

When he was three years old, his father was murdered, and Dora was left with no means to support herself and her children. She asked that they be placed in the nearby Battleford Indian Industrial School. Alex was a good student and an exceptional athlete, and he excelled at boxing, cricket and soccer.

He finished school, moved to Edmonton and landed a job in a machine shop owned by his brother-in-law David Gilliland Latta, a former Mountie who had married his sister Emily. Alex moved in with them at their house at 9131 Jasper Avenue. He later lived in the Reed-Robinson Block at 9533 Jasper Avenue and in suite 1 at the Buena Vista Apartments at 12327 102nd Avenue.

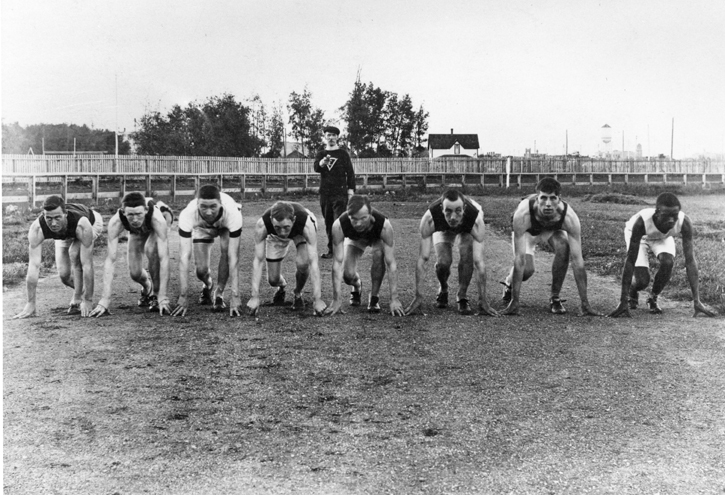

With encouragement from a friend, he began to run competitively. He came second in his first formal competitive race, a one-mile at Fort Saskatchewan on May 24, 1909. The following month, he won a five-mile race at the Edmonton Exhibition with a time of 28 minutes and 41 seconds. Then, in Lloydminster on July 1st, he set a new Western Canadian record at the Mayberry Cup, covering the five miles in 27 minutes and 45.2 seconds.

Victories came one after another for him, and in multiples at the same event. He won the half-mile, the one mile, the two-mile and the five-mile at the Alberta Provincial Championships in Lethbridge on Dominion Day, July 1, 1910. On Christmas Day, 1910, he set the record for the Calgary Herald’s annual 6.33-mile race, finishing the snow-covered course in 34 minutes and 19 seconds.

He became the only Alberta athlete to qualify for the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, and was running third on the fourth lap of the 5,000-metre final when he developed leg cramps and finished eighth. He was awarded an Olympic Merit Diploma and a medal, and Edmontonians celebrated his return home with a parade down Jasper Avenue.

Decoteau became the first aboriginal member of the Edmonton Police Department as a constable on January 16, 1911 and was one of the first motorcycle policemen in the city. In 1913, he was part of the police escort for the party of dignitaries that opened the High Level Bridge. Recognizing his diligence and dedication to the job, the police chief promoted him to Sergeant on April 11, 1914 and he was placed in charge of the No. 4 Police Station on 102nd Avenue and 121st Street.

It became normal practice for Decoteau to win several distance events on the same day, from one mile to 10 miles. One of his typical days was July 1st, 1914, when he competed in Edmonton’s Amalgamation Day Sports and set an Alberta record for two miles and then went on to win the half-mile and the mile later that afternoon.

Several trophies were permanently awarded to him because he was winning them so regularly the officials decided they might as well dispense with the formalities of having him compete for them. Retired Edmonton Journal Sports Editor George Mackintosh wrote that “in distance events, Alex Decoteau was probably the best ever seen around here, and he was still improving when he answered his country’s call.”

Decoteau joined the Canadian Army in April 1916 as a private in the 202nd Infantry Battalion, nicknamed the Edmonton Sportsmen’s Battalion. He was transferred to the 49th Edmonton Regiment and arrived in France the following year. During the time Decoteau was stationed in Europe, he participated in two notable races in England, including a five-mile race in a military sports day in Salisbury, England, which he won.

The trophy was late arriving and so King George V, who was presiding over the event, awarded Decoteau his own gold pocket watch. Decoteau treasured the watch and carried it with him throughout his stay in Europe. The next day, he ran to the location of what he thought was a foot race but discovered it was a bicycle sprint. So he borrowed a bike and won the race.

In a letter to his sister from Belgium dated September 10, 1917, Decoteau wrote of missing home, wartime conditions, the soldiers’ attitudes and his encounters with sickness. “I was taken ill with trench-fever, and didn’t leave my bed for about ten days. I am about over it now, though my legs still pain at times, especially during wet weather. It’s just like rheumatism and many a sleepless night I had to put up with.”

He wrote that he was “laying on the ground, trying to finish this letter before dark. Many an hour we pass away talking of old times and wishing we were all back home again… Of course there’s work to be done yet and I spose will stay here till it is finished.” He ends the letter by writing: “Give my love to Grannie when you see her. Love to the children. Remember me to what few friends I’ve left. For yourself, good wishes, love and affection, from your brother Alex.”

Seven weeks later, on October 30th, 1917, Decoteau was killed by a sniper’s bullet, just short of his 30th birthday. There is no telling how far or how fast he would have run if he had not prematurely given his life to our country in the Battle of Passchendaele.

It is said that the German sniper who shot him took the pocket watch but Decoteau’s comrades later killed the sniper, recovering the treasured memento and sending it home to Decoteau’s mother. He was buried in the Passchendaele New British Cemetery near Zonnebeke, Belgium, alongside 649 other fallen Canadian soldiers.

The legacy of Alex Decoteau was largely ignored until 1966, when Edmonton police officer Sam Donaghey discovered a news clipping about him in the bottom of a file drawer. Donaghey began to research and write about him, and his work led to Decoteau being inducted into the Edmonton Sports Hall of Fame the following year.

Ten years later, Donaghey was inducted into the City of Edmonton Historical Hall of Fame for his research on the history of the police service in Edmonton and on Alex Decoteau. His work not yet done, he worked to induct Decoteau into the Alberta Sports Hall of Fame and Museum, and in 2001, Decoteau was recognized posthumously.

In 1985, the Red Pheasant First Nation, First Nations veterans, Canadian Armed Forces representatives and a 10-member Edmonton Police Service honour guard took part in a ceremony to bring Decoteau’s spirit home from Belgium. His family donated his extensive collection of medals to the Edmonton Police Service, and they are part of the collection at its museum and archives in the downtown station.

Decoteau has also been inducted into the Edmonton City Police Hall of Fame, the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame and the Saskatchewan First Nations Sports Hall of Fame. As part of the city’s centennial celebrations in 2004, he was named one of the 100 Edmontonians of the Century.

In April 2014, the Edmonton Police Service made him the subject of Legacy of Heroes, a digital comic. Decoteau Way, west of 97th Street and south of 144th Avenue, is named is in honour, as is Decoteau Trail, a walkway that runs from 80th Avenue to 87th Avenue, east of 184th Street.

Construction on a park bearing his name is to begin in 2016 on the northwest corner of 105th Street and 102nd Avenue. The idea was kickstarted by a group of students at Patricia Heights Elementary after they learned about Decoteau in class. It quickly gained support of the downtown community and Edmonton Police Service, and the park is being designed as a year-round gathering space.

© Lawrence Herzog 2015