Dime novelists and reporters from the days of the earliest flights were only too happy to feed that appetite with purple prose that makes modern eyes roll uncontrollably. Some pilots have been content to oblige their audiences too, and there’s a saying in the aviation community that when you talk to certain people you should bring a shovel. You know, to dig your way through the B.S. When I started researching Edmonton’s golden son of aviation, Wilfrid “Wop” May, I had that shovel in the back of my mind, just in case. It turned out I didn’t need it, though, he was the real thing. An honest to goodness hero.

Many Edmontonians – especially of a certain generation — remember May fondly, but younger folks and newer transplants might need a quick refresher. Wop May was born in 1896 in Manitoba but the family moved to Edmonton in 1902. He joined the Royal Flying Corps during the First World War and became famous for distracting the German air ace, Manfred von Richthofen (aka the Red Baron) in France, by unintentionally becoming live bait. His school friend Roy Brown and ground forces then brought down the Baron’s red Fokker triplane and May became instantly famous. He went on to be awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross and credited with shooting down 13 enemy aircraft.

Back in Edmonton after the war, he was at the forefront of the burgeoning local aviation scene. He founded the first air service in Edmonton in 1919 and flew with several partners over the years under different company names. He was also one of the founders of Blatchford Airfield in 1927 (the first licensed air harbour in Canada) and the Edmonton and Northern Alberta Aero Club in 1928, the predecessor of the Edmonton Flying Club.

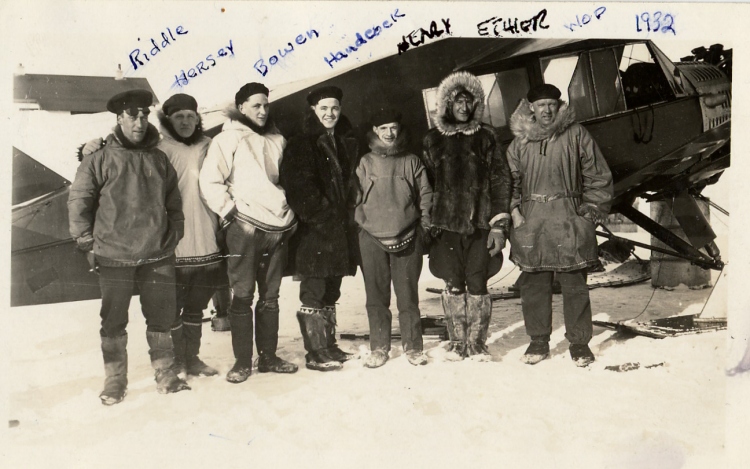

It was his flights of daring that really got him attention. He flew the first aerial police pursuit in 1919, delivered diphtheria anti-toxin to Fort Vermilion in an open-cockpit plane in January 1929, then the first airmail above the Arctic Circle that December (in a much more comfortable cabin airplane, although that didn’t stop the Christmas turkey and rum from freezing). In February 1932, he and his Bellanca bush plane helped the RCMP in the hunt for the Mad Trapper of Rat River (aka Albert Johnson) in the Yukon after the latter had killed and wounded several Mounties and evaded capture for weeks. May not only transported supplies and searched for tracks, he saved Constable Hersey’s life by flying him to the hospital in Aklavik after Johnson shot him in the final standoff. Later he flew out Johnson’s frozen, bullet-riddled body to the Mounties at Aklavik – with mechanic Jack Bowen forced to sit on it in back, apparently.

During these first decades of flight in Edmonton, he also took up paying passengers for rides in his open-cockpit planes, using farmers’ fields as airstrips. He inspired a passion for flight in more than one youngster during these trips, including one of Edmonton’s first aviatrixes, Marjorie Chauvin. Her dad gave her a flight with May for her fifteenth birthday and she was determined to learn to fly. Unfortunately, not everyone thought she should: Chauvin had to threaten to sue the club when the instructor told her women weren’t allowed.

It wouldn’t have been May, though. As Alberta’s first licensed female pilot, Gertrude De La Vergne, later noted: “It was Wop May… who encouraged me to do aerobatics. I still vividly remember doing inside and outside loops with Wop.” While May might have been progressive he was also a pragmatist, and when De La Vergne asked about flying the mail on the Edmonton to Aklavik route with May’s company, she says: “They told me a woman would not be suitable. The commercial licence was too expensive to take without the assurance of finding work so I regrettably gave up flying about a year later.”

By the Second World War, Wop May was manager of No. 2 Air Observer School (AOS) at Edmonton, and hired the only female Link Trainer ground instructor in Canada during the war, Margaret Littlewood. “He was not a man to dilly-dally with problems,” she said later. “He thought I was qualified and he didn’t care that I was a woman.” While managing No. 2 AOS, he also pioneered search and rescue operations for the Royal Canadian Air Force – critical with the thousands of planes being flown up from Montana to Alaska along the Northwest Staging Route (often by American ferry pilots with no northern bush experience).

Wop May died in 1952 on a hike in Utah with his 17-year-old son, Denny; he was only 57 years old. His legacy lives on thanks to the dedicated efforts of his son, daughter-in-law Margaret, and her sister Sheila Reid. They have gifted his artifacts and documents to various heritage institutions in Canada and made sure the public can access them. They have written books on his life, created a website, and even recreated that 1929 mercy flight to Fort Vermilion – although this time in a much more comfortable RCMP Pilatus PC-12 plane. Denny and Marg continue to travel to schools around the area, giving a new generation an old hero.

The air-minded city he loved has not forgotten him. Walk around Edmonton and you can still spot tributes to him: there is the Mayfield neighbourhood and park (although Mayfair Park was renamed William Hawrelak Park in 1976), a mural on the west side of the Alberta Treasury Branch building, and sometimes at Fort Edmonton Park interpreters still bring him to life on 1920s Street.

Wop May’s reputation also extended far beyond the city limits. Canadian balladeer Stompin’ Tom Connors celebrated him in song, and he was awarded medals by both the British the Americans. NASA even named a rock on Mars after him. We live in an era skeptical of heroes, but May might just be one. Whatever it was, if it involved an airplane, he got the job done and he did it with flair. Maybe even a little swagger.

© Danielle Metcalfe-Chenail 2014

Sources/further reading:

- www.wopmay.com

- “Wop May,” Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame website: www.cahf.com

- City of Edmonton, Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie

- Tony Cashman, Gateway to the North

- Sheila Reid’s books, Conquer the Sky and Wings of a Hero

- Denny May, More Stories about “Wop” May

- Alice Gibson, Canada’s Aviation Pioneers: 50 Years of McKee Trophy Winners