At the time of Treaty No. 6, much change and settlement was taking place in the West, with displacement and migration routes of Indigenous Peoples being altered to accommodate foreign populations. With these populations came understandings and misconceptions of the local Indigenous Peoples. These racist and discriminatory perceptions were pervaded at all levels of governance and community in a young Canada. In a letter received by Sir John A. Macdonald on March 16, 1881, P. H Belcher and John A. McDougall outlined these perceptions in a resolution regarding a reserve for Pap-pa or Papaschase. The resolution stated the reserve “…be located at least 20 miles from this settlement, on the following grounds…they enlisted under their banner all the worthless Indians from the other bands, and the old squaws and pensioners of the Company…” Three years after the issuance of said letter, Chief Lapotac would have his reserve surveyed approximately six miles to the West of the Edmonton settlement by J.C. Nelson. Both of these reserves would be subject to dubious surrender processes, with the former resulting in a total taking up of the lands allotted.

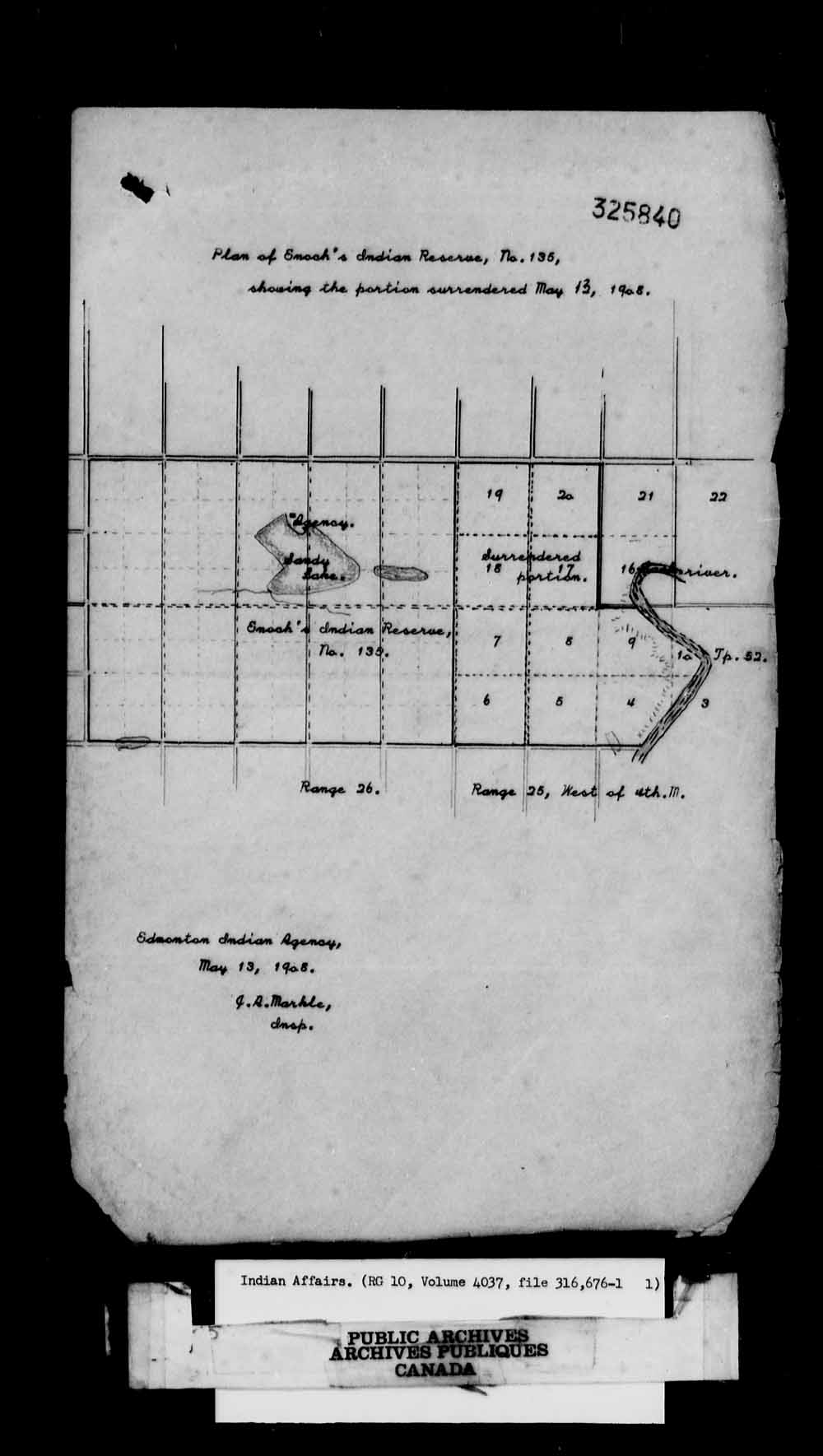

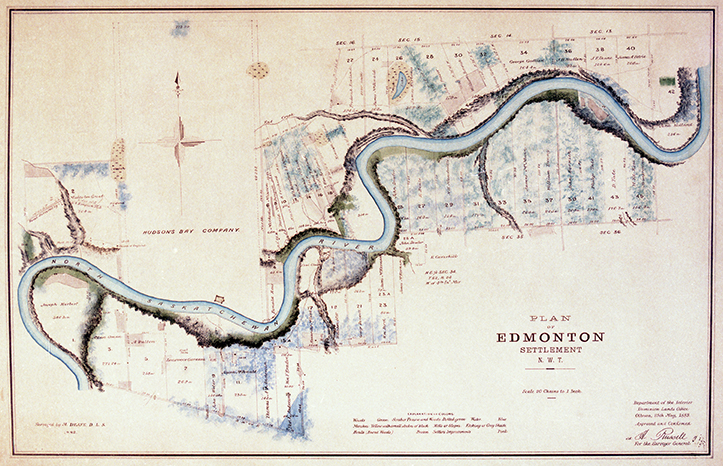

- Map of the Area Surrendered. Edmonton Agency – Stony Plain Reserve – General Correspondence Regarding a Second Land Sale (Maps). Image courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada, Online MIKAN no. 2061667.

In its initial state, Chief Lapotac’s reserve, later known as Stony Plain Indian Reserve and finally Enoch Cree Nation, would be approximately 44 square miles or 44 sections of land. The reserve encompassed a land base that stretched from present day Acheson, closer to Spruce Grove, then the banks of the North Saskatchewan River on its South East Corner. The first significant surrender took place on January 20, 1902 in which twelve sections of the Northern portion of the reserve were surrendered and taken up for settlement. The sale of these lands attracted many purchasers including McDougall and Secord among others. In subsequent discussions, obligations and payment to Enoch would be questioned when the government approached with another request for surrender.

Following a prominent role in the surrender of the Papaschase reserve in 1894, the “Honourable” Frank Oliver would rise to the position of Minister of the Interior and Superintendent General of Indian Affairs in 1905. In his role, Oliver would continue to push the process of Indian land surrenders for the benefit of settler society, and this was evident in the events leading to the May 13, 1908 surrender in question. On November 4, 1907, Minister Oliver would send an internal memo to Frank Pedley, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, requesting his views on the possibility of surrender of the Stony Plain Indian Reserve. On November 11, 1907, Pedley initially replied with hesitancy to the notion of surrender, citing input from the surveyor that the Band “would be very much opposed to giving it up…” Not to be denied, Oliver provided the order for the Indian Agent, James Gibbons, to take up the issue of surrender of the reserve in whole or in part with the Nation. On December 14, 1907, Gibbons would write back to Mr. Pedley, indicating that he had approached the issue with the Band, and that most would be open to surrender, apart from three men who would not discuss the issue at all.

Shortly following this correspondence, Mr. Gibbons would no longer be the Indian Agent in the Edmonton Agency, and the correspondence and duty to attain a surrender would be passed on to J. A. Markle, Inspector of Indian Agencies. In his first reply to the issue, Markle would inform the Department that Gibbons broached the issue with the leaders of Enoch via telephone, and that he had been informed “…they did not want him to come on the reserve to talk about such matters.” However, not paying heed to the desires of the Band, the Inspector still requested from the Department two blank surrender forms. The requested forms were acknowledged as sent on January 9, 1908, and by May 13, 1908, J.A. Markle had secured a surrender of an additional ten sections or 6300 acres of Enoch’s reserve lands, lands which at the time were valued at over $100,000.

In official documentation sent to the Department, the surrender occurred on May 13, 1908 in which 4 principal men agreed to the conditions outlined. Additional documents retained in the same file seem to contradict the surrender documents, highlighting a vote taken on May 15, 1908 in which a tallied vote was fifteen for and twelve against. So immediately, one questions whether the Nation was properly informed as to the process, and the validity of dates in which discussions took place. These questions were conveyed to one of the largest opponents to the validity of the surrender, an Oblate priest in the area, Father Christophe Tissier. With information provided by the Band, the Father issued a confidential three-page letter on May 18, 1908 to Minister Frank Oliver. Tissier would outline a process of intimidation and coercion utilized by the Inspector to manufacture consent of the Band.

- Letter from Father Christophe Tissier. Edmonton Agency – Stony Plain Reserve – General Correspondence Regarding a Second Land Sale. Image courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada, Online MIKAN no. 2061667.

- Letter from Father Christophe Tissier. Edmonton Agency – Stony Plain Reserve – General Correspondence Regarding a Second Land Sale (Maps). Image courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada, Online MIKAN no. 2061667.

- Letter from Father Christophe Tissier. Edmonton Agency – Stony Plain Reserve – General Correspondence Regarding a Second Land Sale (Maps). Image courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada, Online MIKAN no. 2061667.

Allegations were detailed in the letter by Tissier, stating that that the Inspector had placed the obligations from the first surrender as conditional depending on a second surrender. Further to that, it was stated that Markle had conspired to remove the leader at the time, Mistatim (Mr. Jim), and replace him with another that was more willing to surrender. The letter also included statements regarding members being denied the ability to vote, and advisors being turned away from the discussions. Indications of the quality of the land, presence of coal deposits and some of the best timbers in the area were outlined by Tissier and supportive of a reluctance to surrender. Lastly, Markle was implicated to have threatened economic sanctions from the settlement at Edmonton. To contrast this, the Inspector promised that if the Nation were to agree to surrender, an offer of 10lbs of meat and 5lbs of flour would be given to each man on the reserve every week. Tissier would be moved by the information shared with him by the Nation; stating, “I cannot say anymore that he [Markle] is a gentleman. He [sic] not acted as an honest man…” and that the actions of Markle were an “…injustice done to good Indians and that I disapprove of the Inspectors dealing with the Indians”. Minister Oliver would forward said confidential letter to the Inspector, and a carefully crafted justification would shortly follow.

In a detailed five-page rebuttal dated June 29, 1908, Inspector Markle would outline his version of events and garner statements of support from Agent Urbain Verreau, Clerk William Black and Interpreter John Foley. Markle would clarify that the Father was an aged gentleman whom was coerced and the issue was that of “…goats leading the shepherd”. Continuing in his description, Markle would state that from the previous surrender, the Band had already expended some funds, and in order to attain what they wanted, they would need another surrender of land. The portions selected were influenced by the requirement for “…settlers living southerly… have a road along the eastern boundary of the reserve, instead of now across the reserve…”

The rebuttal stated the initial conditions of surrender were denied, and upon return, the Band requested more leadership, in the form of one Chief and four Headmen to decide. This request, as recalled by Markle, was denied and he informed them they could only have one Chief and one Headman. Which, in later correspondence from Mr. Pedley, would prove false as the Indian Act of the time allowed for Enoch to have one Chief and two Headmen. Markle recognized and affirmed that the leadership did change during the negotiation, and that the Department accepted a new leader mid-negotiation. Lastly on the issue of the promise of meat and flour, Markle recalls “…the Indians were told that if they agreed to the surrender…10 lbs. of beef and the 7lbs. of flour would be regularly issued to them as sure as their treaty money. If they refused… they must not look for free food but depend on their own exertions to meet their wants.” The Inspector also confirms that some were denied the right to vote, and that his understanding was that they were visitors, however being from the South it does not seem reasonable for him to make such assertions. Markle closes his testimony with a hesitation for any recourse and that the Father dedicates himself to “…the spiritual welfare of himself and others…”

- Map of the Area Surrendered. Edmonton Agency – Stony Plain Reserve – General Correspondence Regarding a Second Land Sale (Maps). Image courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada, Online MIKAN no. 2061667.

In order to ensure the validity in the eyes of the law and parliament, and satisfied with the explanation of Inspector Markle, the surrender would be fast-tracked parallel to the disputes of the Band and Tissier. On July 11, 1908, Minister Oliver accepted the terms of the surrender, and the issue was passed with an Order in Council on July 21, 1908. On July 29, 1908, a letter of reply was officially forwarded to Father Tissier from the Department announcing that the second hand information he received was incorrect, and that surrender was undertaken with good faith. Tissier would later denounce the decision of the Department in another reply, and the notion of Agent Verreau being absent at the surrender discussions brought into question. At this point, the Department had begun and continued with its processes of opening of the lands for purchase.

- Map of the Land Surrender on today’s road system. Map created by Robert Houle. All rights reserved, do no reproduce without permission.

Moving forward, the conditions agreed to by the Band would not be met hastily, with the Department attempting to change the terms and applying unilateral alterations to the distribution of the goods agreed. The lands would be sold at auction, with the total price attained being less than initially forecasted. Coal deposits mentioned by the Father and the rich timber lots would be utilized with full benefit of the settlers who purchased said lands at auction. Taken as a single instance, it may be concluded that Father Tissier was mistaken and the surrender was legitimate. However in 2003, the Government of Canada and Siksika Tribe settled a claim for $82 million that alleged Inspector J.A. Markle had failed to properly inform the Band of the total area surrendered in a 1910 agreement. As the years progressed, the curious case of the 1908 Enoch surrender would be overwritten by settler colonial history. Large blossoming communities of Secord, Hamptons, Cameron Heights and others would develop at increased rates, while the obligations under Treaty and manufactured surrender go on unfulfilled.

Sources:

http://www.ammsa.com/publications/alberta-sweetgrass/siksika-land-claim

Indian Affairs RG10, Volume 3842, File 72,213

Indian Affairs RG 10, Volume 3737, File 27596