Traversing across the North Saskatchewan River on the Groat Road Bridge and climbing the Valley Road has little significance other than a pristine view of Edmonton’s river valley. However, this is not the case for all who call this great city home.

Frank Oliver was born Francis Bowsfield in the Peel County of Ontario in 1853. Raised in a staunch Liberal household, Oliver would absorb and retain the views of his father Allan Bowsfield. With the death of his mother at an early stage in his life, and the haste of his father to remarry, Frank would leave Ontario on bad terms and take on his mother’s maiden name. Performing odd jobs upon arrival in the North West Territory, Oliver began to interact with the local populations and create a reputation for himself, both good and bad.

- Portrait of Frank Oliver. Image courtesy of the Provincial Archives of Alberta A15944.

Many who had interactions with Oliver would describe him as a dedicated, stubborn, tumultuous and strategic individual. Examples of this stubbornness can be found in correspondence regarding article submissions to Maclean’s Magazine. When confronted with allegations of misrepresentation regarding the Honourable David Laird, Oliver responded with; “I fear that Ms. Matheson is over sensitive on the subject of her father. I certainly did not intend any reflection on Lieut. Governor Laird’s conduct… and in looking over the article I am compelled to say I don’t see any”. Similarly, when confronted with the proposition of having his work re-written, the tumultuous Oliver proclaimed, “…I would want it to be made perfectly clear that I was in no way responsible for the style, manner, or selection of the facts appearing in the re-write”.

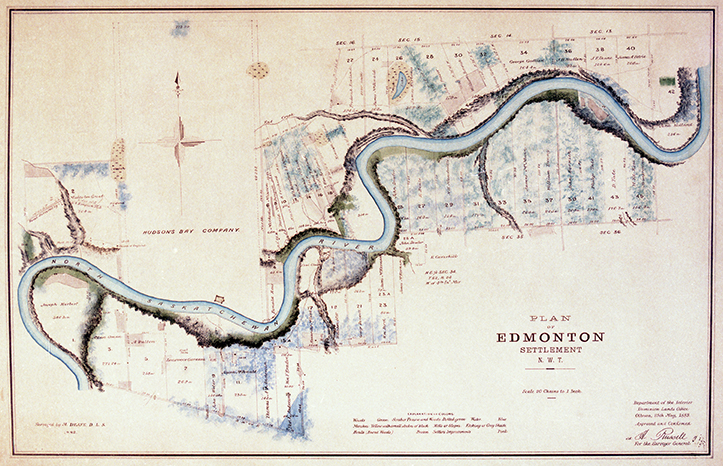

During the late 19th century, the West was still a very secluded territory. Word from the East took some time to reach the bustling populations in what was an infantile Edmonton. Faced with this reality, Oliver sought a means to enhance this transmission of information and feed his true passion of journalism. Founding the first newspaper in the region with partner Alex Taylor, Oliver began to shape the Western narrative. The Edmonton Bulletin began publication in 1880, with Oliver as editor. Focusing on national updates and local happenings, the Bulletin became the ideal mechanism for a climb to power.

Utilizing the Bulletin as a soapbox, Oliver was able to convey Liberal ideologies from Ottawa, and champion for political change in the West. Aligning himself with “Old Timers” whom shared similar beliefs, Oliver quietly established a movement at the territorial level. The Bulletin became a voice for the progressive leaders who sought to change the landscape both physically and politically. These voices called for many controversial policies and approaches that the early Canadian government had imposed, and would impose in the years to come. One such policy was the surrender of Indian Reserves in the name of progress.

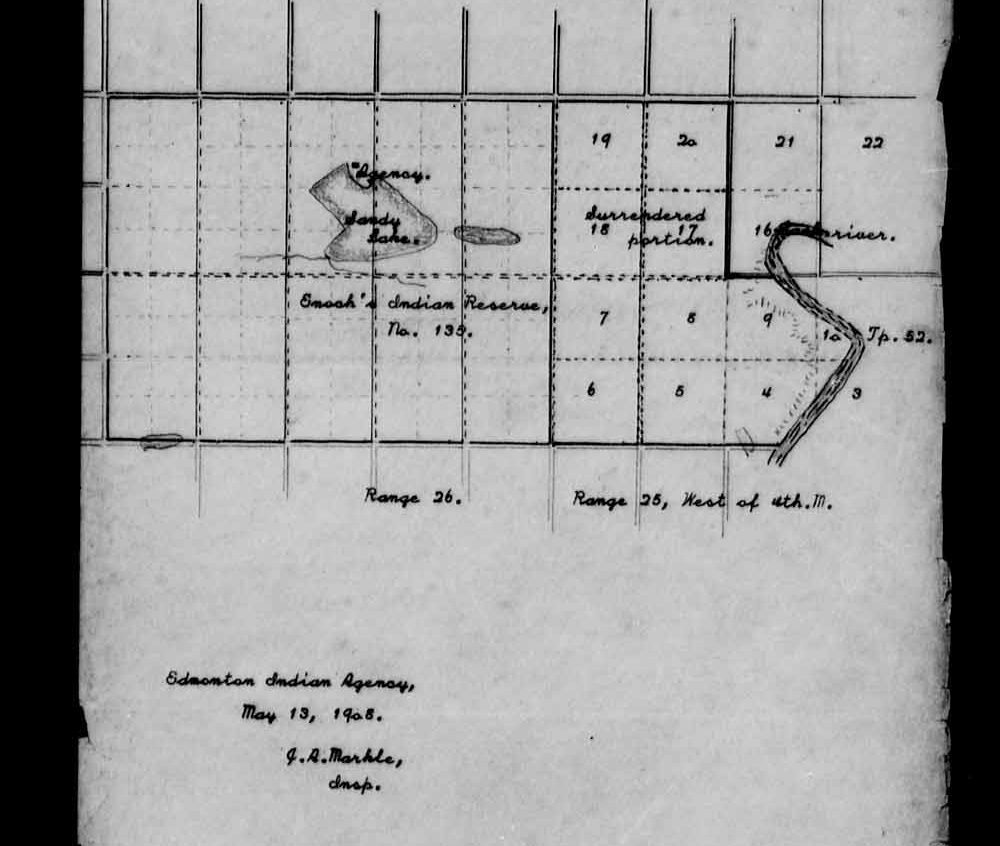

At the helm of the Bulletin, Oliver began to petition and lobby for the unconditional surrender of many Indian Reserves or portions of reserves in the immediate vicinity of Edmonton. This process was fuelled by common, misguided, and outright discriminatory beliefs directed towards the First Nations peoples. Expressions of these beliefs were often kept from being out rightly conveyed by Oliver, however evidence of support is reflected in statements published in the Bulletin;

“It is well known that an Indian Reserve located near a town is a cause of trouble and general demoralization to both whites and Indians” and “Now is the time for the Government to declare the Reserve open and show whether this country is to be run in the interests of settlers or the Indian”.

- Frank Oliver with the Council of Northwest Territories circa 1884. Image courtesy of the Provincial Archives of Alberta PR2007.0279.0001.

Petitioning for these controversial policies gained Oliver notoriety and in 1883 he was elected to the blossoming Northwest Council. Continuing to serve in local politics for some time Oliver upheld advocating through the Bulletin for continued land surrenders around Edmonton. This pressure would lead to the eventual surrender of the Papaschase Reserve in 1894 just South of the growing settlement of Edmonton. Whether or not Oliver received some personal gain remains to be explored, however, similar questions of personal gain would emerge with future land surrenders.

Two short years after the Papaschase surrender, Oliver would be elected as the first Member of Parliament for Alberta. Within nine years of being elected, Oliver would become the Minister of the Interior and the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs. In his new position of power, Oliver would maintain the work of the government and successfully negotiate the surrender of the Michel Reserve near present day Villeneuve, Alberta. In regards to this surrender, it has been alleged that J.J. Anderson, Oliver’s son-in-law, was involved in land speculation on the Minister’s behalf.

When Indian lands are bought after an initial surrender, depending on the area, a profit can be expected through speculation and re-sale. In relation to the reserves in the Edmonton area, “The block of land claimed by Papastayo’s band consists of the choicest portion of this district”. This type of designation would apply to the Michel Reserve and would certainly turn a profit. In 1909, according to correspondence and bank information, Minister Oliver had some $50,000 in his personal accounts. Upon questioning, Oliver would state that the monies were not acquired through official governmental business, but rather personal dealings.

- Frank Oliver speaking from balcony of Selkirk Hotel on being appointed Minister of the Interior, April 10, 1905. Image courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives, EA-10-2050. Do not reproduce.

Looking back today, one can hardly comprehend how an individual of significant proximity to a Member of Parliament, let alone the Minister of the Interior, could play a key role in land speculation. To further complicate the situation, according to correspondence from legal counsel, Oliver did hold mortgages for Indian lands. In a letter from George B. O’Connor it would be stated “The Trust & Guarantee Co. refused to pay the fees for registering the transfer for the Indian Reserve property…” These same properties may be what Oliver refers to when stating “…520 acres of valuable land”, and “…520 acres of land seven miles from the centre of the city” in later conversations. Examination of archival information displays that Oliver was connected to the Indian Land surrender industry as an advocate and possible participant, a dubious industry upon which portions of Edmonton were built.

© Rob Houle 2015

—

Resources

“The Alienation of Indian Reserve Lands During the Administration of Sir Wilfred Laurier, 1896-1911: Michel reserve #132”, Tyler and Wright Research Consultants, August 1978.